It’s an unboxing video! I hear those are popular. Only what I’m unboxing is a pair of spider egg cases.

Spoiler: I don’t find any spiderlings inside. I find evidence of them being there, in bits of molted cuticles, but nothing was moving. I’ll let them warm up for a few days and look again.

If you want to know more about how spiders overwinter, here’s a source:

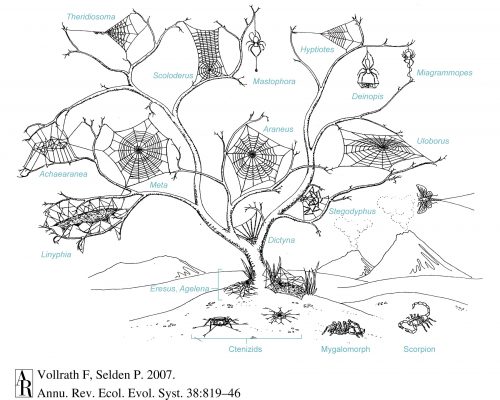

Tanaka K (1997) Evolutionary Relationship between Diapause and Cold Hardiness in the House Spider, Achaearanea tepidariorum (Araneae: Theridiidae). Journal of Insect Physiology 43(3):271-274.

The relationship between diapause and cold hardiness of the house spider, Achaearanea tepidariorum, differed geographically. In a cool-temperate population, enhanced chilling tolerance and supercooling ability were observed in diapause individuals, whereas a subtropical population showed only chilling tolerance. Because this spider is considered to be of tropical origin, it would follow that the ancestral diapause of this spider was equipped with chilling tolerance, but not with an increased supercooling ability. It seems that the ability to lower the supercooling point evolved through natural selection in the course of expansion of this species to the northern climates.

Now I have an excuse to visit Florida on a collecting trip, to gather representatives of southern populations. Maybe I should go in, like, February.

One other thought I had about the barrenness of these egg cases: it’s like the Donner expedition. Maybe one of the ways spiderlings survive the long cold winter is by eating their siblings, and this winter was particularly harsh.