In September and October 1982, seven people died in Chicago after taking Tylenol caplets laced with cyanide. The murderer purchased packages, poisoned them, then placed them back on store shelves where unwitting victims purchased them. No one was ever arrested for the crime.

James Lewis died on July 9, 2023. He was the only suspect for the seven murders. He was convicted and sentenced to prison for extortion, after sending a letter to Johnson & Johnson demanding money (which was never paid). Suspicion of Lewis’s guilt increased when, in a conversation recorded by the FBI years later, he admitted to details that were only known to authorities. He was never arrested, likely because prosecutors felt they had insufficient evidence to convict him, wanting to avoid double jeopardy.

James Lewis, suspect in the 1982 Tylenol murders, dies at 76

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (AP) — The suspect in the 1982 Tylenol poisonings that killed seven people in the Chicago area and triggered a nationwide scare has died, police confirmed on Monday.

Officers, firefighters and EMTs responding to a report of unresponsive person about 4 p.m. Sunday found James Lewis dead in his Cambridge, Massachusetts, home, Cambridge Police Superintendent Frederick Cabral said in a statement. He was 76, police said.

“Following an investigation, Lewis’ death was determined to be not suspicious,” the statement said.

No one was ever charged in the deaths of seven people who took drugs laced with cyanide. Lewis served more than 12 years in prison for sending an extortion note to Johnson & Johnson, demanding $1 million to “stop the killing.”

When he was arrested in 1982 after a nationwide manhunt, he gave investigators a detailed account of how the killer might have operated. Lewis later admitted sending the letter and demanding the money, but he said he never intended to collect it.

This obituary/news item on Lewis gave his suspected motive: revenge against Johnson & Johnson for a medical product that failed and killed his five year old daughter. There’s a little more below the fold.

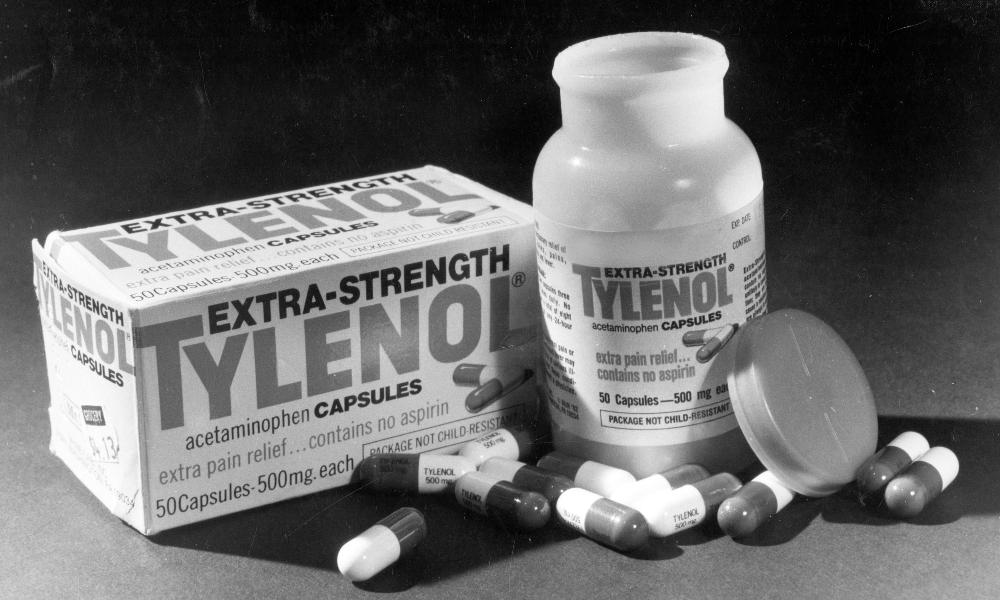

The Chicago Tylenol murders were (unsurprisingly) the event that changed commercial packaging forever. Below is a picture of the packaging at the time: unglued boxes with folded tabs, and a simple pop top on the bottle. Tampering with the packages would have easily gone unnoticed.

Johnson & Johnson’s response was to pull all boxes of Extra Strength Tylenol from store shelves, destroying them all, and only releasing newly made pills in triple sealed packaging (plastic wrap, glued boxes, internal tamper-proof seal), which is how all medicines are packaged now, as are many foods or internally consumable products (e.g. toothpaste).

Undoubtedly much of Johnson & Johnson’s response was about protecting the brand and corporate image. But to their credit they handled the incident responsibly, they did not resell, repackage, or export the old product to save money, avoiding any risk of further deaths. While the company was not directly to blame, they did agree to financial settlements with the seven families of the victims.

I remember all that.