A recent study by the University of Rochester Medical Center has found that the same chemical used to color blue M&Ms and blue Gatorade can also be used to heal spine injuries. The chemical, Brilliant Blue G (BGG) blocks P2X7, known as the “Death Receptor.” This stops the signal that tells motor neurons to undergo apoptosis (cell death). When rats with spinal cord injuries were injected with BGG, they were able to walk again with a limp.

How awesome is that?

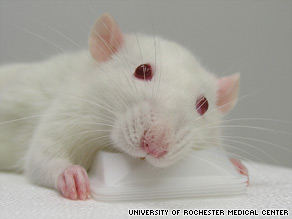

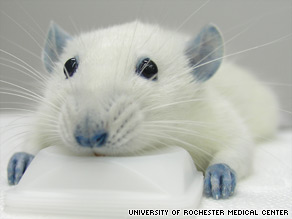

And BGG has the added benefit of making rats extra adorable. They go from this: To this:

To this: Want. Now.

Want. Now.