I see a little brouhaha has formed here among the godless over cats vs dogs. It’s an issue that does elicit surprisingly strong feelings among pet owners. Of course, no one can settle the question of which is better, that’s a subjective call. But we can look at why dog and cats behave so differently. We just need to start at the beginning, with a little evolution and a dash of natural history!

Cats and dogs belong to the diverse order Carnivora, made up of Canids including foxes and coyotes, Felids like lions and tigers, Ursidae like bears, Pinnipeds such as seals and walruses, Mustalids like weasels and minks, and even Procyonidae of which the best known member is the racoon or skunk. Carnivora trace their furry, warm blooded ancestry back to the mammal-like synapsids of the Permian over 250 million years ago. Something like a cute little cynodont was the ancestor of both cats and dogs and, incidentally, people. But like most mammals, the order of carnivores would have to wait until 65 million years ago, when non avian dinosaurs had exited stage left, before they could really blossom as a taxon.

Cats and dogs belong to the diverse order Carnivora, made up of Canids including foxes and coyotes, Felids like lions and tigers, Ursidae like bears, Pinnipeds such as seals and walruses, Mustalids like weasels and minks, and even Procyonidae of which the best known member is the racoon or skunk. Carnivora trace their furry, warm blooded ancestry back to the mammal-like synapsids of the Permian over 250 million years ago. Something like a cute little cynodont was the ancestor of both cats and dogs and, incidentally, people. But like most mammals, the order of carnivores would have to wait until 65 million years ago, when non avian dinosaurs had exited stage left, before they could really blossom as a taxon.

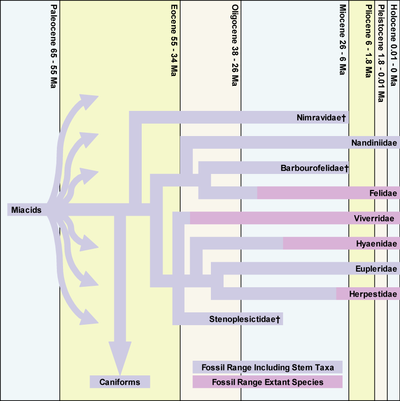

Extant carnivores descend from a genera called Miacids, successful small game hunters that appear in the fossil record about 55 million years ago. It’s unknown if the Miacid ancestors of cats and dogs had already diverged by that time. But if they had they probably looked a lot more like one another than cats and dogs do today. These early Miacids were long, low slung creatures, something like the critter in the image to the left. The evolution of carnivora as reconstructed from fossil and genetic evidence is quite involved, the one below gives an idea of how and when the various lines may have split.

Compressing millions of years of fascinatig megafauna evolution into one sentence, by the time our earliest hominid ancestors came along a few million years ago, wolves and cats had arrived in a big way. Some of them were huge, both probably hunted our direct ancestors and close relatives. There’s a famous juvenile Australopithecine skull cap with two punctures in it that’s a dead ringer for a deep, mortal saber-tooth bite. That’s how it was for millions of years, until we went through our own evolutionary transformation and turned into the deadliest predator of all time. It was our subsequent actions on both wolves and wild cats that made them into the cute cuddly critters they are today.

There is reason to believe humans began some kind of association with wolves around 50,000 years ago and there is evidence wolves were at least partly domesticated and living side-by-side with humans by 30,000 years ago. Over thousands of years, one line of Eurasian gray wolves seems to have mostly won out — lots of inter subspecies breeding aside — and that’s the line that gave rise to lovable family mutts the world over. In part humans accomplished this by selecting for juvenile traits, a sort of permanent puppy-hood, breeding wolves that remained playful and happy in the role of beta to our alpha even as adults. More recently we’ve also bred them into a crazy array of sizes, colors, and shapes, sometimes with tragic genetic consequences, from small enough to fit into a coffee cup to the size of a small pony. They have all kinds of specialities, from sheep dogs to varmint hunters to dogs of war. As a result, dogs today rank as one the most genetically diverse, single species on earth.

Cats on the other hand have a much shorter association with humans. The common house cat appears to be a descendant of a Eurasian/African wildcat hybrid that was probably barely tamed and tolerated in the Nile delta a few thousand years before the first Pharoah was crowned. These wild cats were also selected for permanent kitten-hood so that they would tolerate or ignore us, unlike their wild ancestors which would probably flee in panick if possible or attack without mercy if cornered. They show genuine affection and interest at times, depending on the cat, but few cat lovers would argue it’s as well developed, as instantly visible, and on average as universal, as in dogs.

Because dogs were social pack animals to start with and have been breed to be, among other things, likable — the penalty for being an unlikable domesticated animal was usually harsh indeed — many times longer than cats, it’s not surprising they engage more with humans than cats, or that they’re more trainable and useful, thus more fun for people who seek interaction and maximum communication with their pet. Fifty-thousand or more dog generations vs. less than 10,000 cat generations of artificial selection makes a big difference. One difference is cats are more like a wild animal, little lions in our houses, because they’re less removed from their feral ancestors. And if that raw, independent side of nature is what you like in a pet, then you’re probably a cat person.

Now, if cats had been worked over by humans for 50,000 years like wolves were, we’d probably have house cats the size of Black Labs down to the size of lab rats with similar degrees of trainability, loyalty, and interaction. Cats with all manner of manes and stripes and coats. They would make for more interesting companions imo, certainly more flexible farm and ranch helpers, and they’d surely be wickedly bad ass guard animals. Can you picture the fate of any poor burglar who broke into a house inhabited by the loyal family guard tiger?

However they came to be and whichever you prefer, there’s no doubt cats and dogs have become our best friends in the animal kingdom hands down. The partnership we have struck with these adorable, furry creatures has worked out wonderfully for all three species. Cats and dogs are now so numerous and widely distributed that they have a big evolutionary edge for survival far into an unpredictable future. Most importantly, in the here and now, they offer us a level of reliable comfort and companionship most human beings would be hard pressed to match, all for the bargain price of a bowl of tap water and cheap food, a few scratches behind the ears, and an occasional treat.

I’ve been a cat person all of my life, and we have two that we adore. Mine is a “normal” cat, but my husband’s Maine Coon seems to think that he is a dog. He is polydactyl (has seven toes on one paw, and six on all the rest). When the hubby arrives home, he must first hold the cat like a baby, rock him in the rocking chair and give him a thorough scratching, or Dax is unhappy. Then, whenever hubby is in his recliner with his laptop, he must also hold Dax on his lap and scratch him continually.

Recently, I became the lucky partner of a German Shepherd service dog. I’m learning to enjoy his constant companionship and I truly appreciate his aid when I’m negotiating curbs and stairs.

Of course, Dax is still is the boss of the house, and he bullies my poor dog mercilessly.

I think it’s possible that the (now extinct) ancestor of domestic cats may have had a social structure more like lions than the typical loners that most cat species are. Left to their own devices, cats create pride-like groups with a senior male who mates with the females and who makes sure junior males show proper deference, though they are not necessarily kicked out, as they are among lions.

It makes sense if the ancestor of cats was more social than the average cat species, that it was that particular species that was domesticated. Most of our domestic animals are social animals and the ones that aren’t (like snakes) are very recent additions to the pet store.

It is possible that the tendency to social behavior with us and with each other was a post-domestication change, but, as you said, they haven’t been domesticated nearly as long as dogs have. I think that social behavior was part of the original wild cat. Of course, cats are not dogs and their type of sociability is quite different, and varies a great deal from cat to cat.

See, some of us think having a little lion in the house is pretty danged interesting.

(Just sayin’; not trying to reignite hostilities….)

You could be right, I don’t think too much is known about their behavior, as they’re so small and elusive.

Also, the family relationship between mother and kittens is pretty intense. Cats are famously attentive mothers, and kittens learn a lot from them. So the sociability of domestic cats is partly accounted for by neoteny. http://jennifercopley.suite101.com/neoteny—why-adult-cats-retain-kitten-qualities-a142539

Fascinating discussion, and my thanks. A few questions and comments, though. First, I would argue that the early wildcats that seem to be ancestral to housecats were already “cute cuddly critters” (IMO!).

Second, you mention that the ancestors were probably a “Eurasian/African wildcat hybrid”. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I thought that by definition, animal hybrids were sterile because they aren’t the same species?

Third, I seem to remember a National Geographic article about housecat evolution that seemed to suggest that the consensus was that the ancestor was an Egyptian wildcat. Am I wrong?

Fourth, regarding, “They show genuine affection and interest at times, depending on the cat, but few cat lovers would argue it’s as well developed, as instantly visible, and on average as universal, as in dogs.” Hmmph. You haven’t seen our 4 cats.

And lastly, regarding, “Can you picture the fate of any poor burglar who broke into a house inhabited by the loyal family guard tiger?”:

Have you seen a commercial that’s out now (for insurance?), where a couple have adopted a “rescue leopard” for security? I laugh every time I see it. The leopard spends the night staring at the couple in bed, licking its chops.

gvlgeologist, I can field that one. They’re the same species, just different subspecies: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wildcat. (Some biologists class domestic cats as simply a subspecies of Felis silvestris.)

(Though my understanding is that the “hybrids of different species will always be sterile” thing is a rule of thumb, but not a hard and fast one; sometimes species that are closely related can produce fertile offspring. Female ligers and tiglons are fertile.)

Otrame,

Our kids collected cats, and we’ve shared our house with them for over thirty years. At one point, we had eight of them living in our house. I loved to watch their interactions. They did indeed form a “pride”. Even though they were all neutered and spayed, they were all deferential to the oldest male in the pride. He was “top cat”, and always had the sunniest, most comfortable napping spot, and was given first choice at the feeding dishes. When the oldest cat passed away, I swear the rest of them seemed to grieve for a while, then the next oldest would assume “top cat” privileges.

They formed friendships and seemed to mostly bond in pairs. We had one group of three. We called KC and Bexar our “gay guys”, since they really had a thing for each other. However, Bexar had a thing on the side with Lady Diana. Lady passed before the boys, and then they became inseparable. They both deteriorated together, until we had to let both of them go at the same time when they were both eighteen.

The two that we have now are definitely pair-bonded. They play together, sleep together and groom each other. I’m convinced that cats are very social creatures.

Isn’t there an ad on the tv with people trying to save money by using a ‘rescue panther’?

They look as though they are picturing their own fate.

One thing that you leave out of this excellent discussion is another reason for the deep relationship between canis and people, our similar ecological roles. Both wolves and humans filled the role of pack hunting chase predators (in boreal forests and African savannahs, respectively.) This meant that our instincts for social interaction were similar and our inherent tendencies towards cooperative action were reinforced. In contrast, with the exception of African lions, cats are not social hunters. The hostility between cats and dogs (and their human companions) is a reflection of their ecological competition as large animal predators.

BTW, my understanding is that biologically, dogs are merely a subspecies of wolves. Since wolves and domestic dogs can interbreed and produce fertile off-spring, they have not speciated.

@stacy, #5:

Thanks for the info. It’s my non-biologist’s understanding that by definition “species” is a population that can only interbreed and produce viable offspring within itself, but of course (as with ring species) there are always unusual circumstances.

@richardelguru, #7: Look at my comment at #4. You’re right though, it was a panther rather than a leopard.

Species can be an arbitrary concept at times; go back far enough and you will find an ancestor that would not be able to successfully breed with a modern human. It is a fuzzier concept than we often realize. A Great Dane could probably breed with a coyote or a wolf, though in real life, is more likely to be killed (despite the size disadvantage, wolves and coyotes are experienced killers, unlike the average GD), but can you imagine a GD breeding with a Chihuahua? We often define species because two groups do not breed, even if they can. I think in general, the ability to produce fertile offspring indicates genetic closeness, and so when we see infertile, or less fertile, offspring, we are seeing the effects of evolution. Horses and jackasses rarely produce fertile offspring; lions and tigers produce less fertile offspring; humans and chimps are unlikly to produce any offspring (and don’t ask me to explain Mr Spock)

Dog person here. My wife and I have two Maltese, litter mates we got at the same time. They get along very well with people, except small children who tend to terrorize them. They get along with most dogs their size or a little larger. Big dogs present a more variable problem. The black Labrador next door is fine, but other larger dogs, I think, view them as toys to be played with.

However two years ago when my wife and I were waiting on the ferry in Croatia, we met a couple with a pet Rottweiler. Our two little guys and the big guy got along with no problem (lots of sniffing involved, of course).

Then the owner of Rottweiler offered an explanation. The Maltese is a breed created during the Roman Empire and were used as “alarm dogs”. They slept with their owners and if an intruder crept into the home, they would start barking like crazy (our two do it if they hear anything outside). The owner would turn them loose and while the intruder was distracted by the small, cute and non-threatening little Maltese, the guards would unleash the Rottweilers (another Roman breed) on the intruder.

Great story but I’ve never been able the verify it.