Oh, man. This is bad. An article on Vice asks, Are Scallops Vegan?, and if you know the rule of questions in headlines, the answer should be “NO”, but this article actually plumps down on the side of “maybe?”

In the case of bivalves—that is, sea creatures with a hinged shell, such as oysters, clams, mussels, and scallops—the line between plant and animal, especially in regards to cooking and eating, remains unclear. “But, they’re alive,” someone may say who has seen the pulse of oyster flesh or the slow opening and closing of a scallop shell. But so are plants—every carrot you slice and every apple you bite into was once alive, and begins to die as it’s removed from its stem or roots. And while some bivalves, like scallops, open and close their shells by using an adductor muscle, plenty of plants can also independently move.

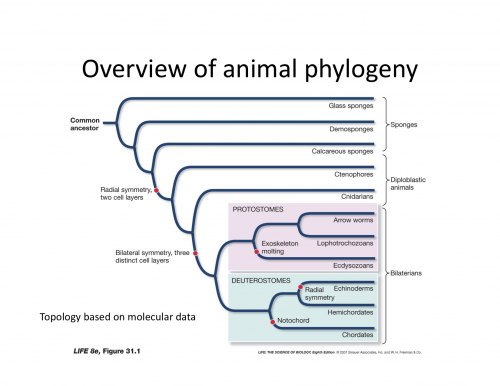

Being alive is not an adequate criterion — it doesn’t distinguish anything in biology. By definition, “life” is “alive”. But whether molluscs of any kind are animals or not is unambiguous — yes, they are animals. They are triploblastic, bilaterian protostomes, members of the lophotrochozoan clade in this diagram.

It’s always a good idea, O Journalist, that when you have a biology question you should ask a biologist, and not just a random layperson you meet at Whole Foods. Or at a local seafood restaurant.

I, a lapsed vegetarian, first heard the argument that scallops could be considered vegan during a recent lunch at Greenpoint Fish & Lobster Co., a Brooklyn seafood restaurant dedicated to sustainability. Though a spot with fish tacos and daily oyster selections may not seem like a vegan’s first pick for dinner, co-owner Vinny Milburn told me that the restaurant has numerous vegan regulars who visit to eat scallops and other bivalves, justifying their consumption, ethically and environmentally, with science. “They feel okay about it because it doesn’t have a central nervous system,” Peter Juusola, general manager at Greenpoint Fish told me.

Uh, they’re not vegans. They’re not even vegetarians. They’re pescatarians. Which is perfectly OK, I’m more of a pescatarian myself, because while I’ve been cutting back, I do eat seafood now and then. I’m not judging them, except to point out that mislabeling yourself because you’re pretending to be more ethical and environmentally sensitive than you actually are is dishonest and a bit yucky.

See that diagram above, with the colored bits labeled protostomes and deuterostomes? All of the members of those groups have nervous systems, every one. So do the ctenophores and cnidarians, although they tend to be more diffuse and lacking in specialized regions. Sponges do not have a nervous system, although their cells do communicate with one another using protein networks that have evolved into our nervous system. Arguing that vegans get to eat anything lacking a nervous system, a dubious claim, would mean you only get to eat sponges. If having localized collections of neurons that function as a kind of primitive “brain” qualifies as an exclusion, you also get to eat jellyfish.

Molluscs do have a central nervous system in the form of a couple of ganglia. Those count.

The killer counterargument, as far as I’m concerned, is that scallops have eyes. You’re not a vegan if you eat something that can look back at you. They’re even pretty blue eyes!

This does not seem to persuade some people, who ignore the physical evidence.

Conclusive evidence on whether bivalves, or even crustaceans, for that matter, feel pain, has yet to surface, but for starters, they “do not have a brain,” Juusola says, demonstrating with his fingers that when a scallop opens and closes, that’s a reaction due to a nervous system, not their nervous system calling out pain or danger.

They have multiple ganglia, which can be demonstrated anatomically, but apparently the argument from “opening and closing fingers” refutes the observable existence of coordinated, interacting sets of neurons.

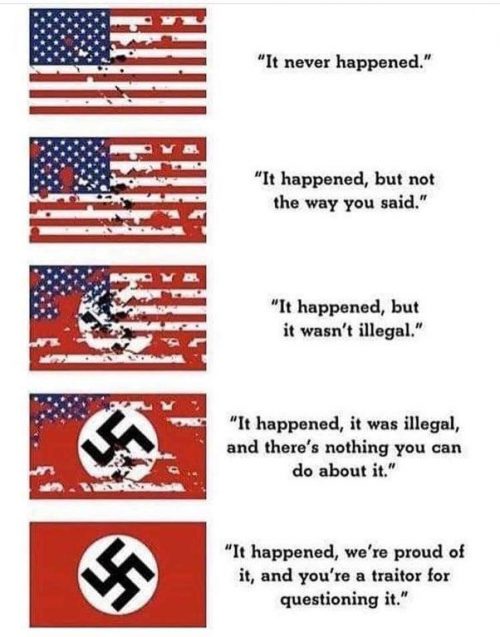

I’m going to have to remember that one. When someone questions me on whether Trump has a brain, I’ll just wiggle my fingers and say, “Obviously, no. See my fingers?” In other good news, we can also legitimize the claim that the rich are brainless non-animals, allowing vegans to eat them.

So what are you waiting for, vegans of the world? Dig in!