I’ve driven by Fort Snelling, the park and the gigantic military cemetery, an uncounted number of times — it’s right by the airport, so if you’ve ever flown into the Minneapolis/St Paul International Airport, you’ve gone by it yourself. It’s right there at the intersection of the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers, so it’s been an important landmark even before the airport was built; even before Minnesota was a state; even before European settlers invaded the territory.

Guess what has our Minnesota legislature — at least, the Republican side — in an uproar now? Historians have added a word to the sign at the visitor center: “Fort Snelling at Bdote“. They haven’t changed the name of the place, they’ve only added an acknowledgement of the Dakota word for this meeting of the two rivers, which sounds like a lovely addition to me, and one that does no harm to the European side of the history, but only extends it to include the longer Indian record of residence.

Unbelievably, Republicans consider this an assault on their version of history.

“Without any public input that I am aware of, the Historical Society has changed the name of historic Fort Snelling, which is a military installation, to historic Fort Snelling at Bdote,” Sen. Scott Newman, R-Hutchinson, told 5 EYEWITNESS NEWS.

He said he’s also heard from veterans who are upset by the signs, and consider it “revisionist” history.

“I think it’s a rewriting of our history and I’m not in favor of it,” he said.

It’s not just a myopic reading of history, the Republicans are planning to punish the historical society by cutting their budget by millions of dollars, possibly costing the loss of as many as 80 jobs (which is fine with the Rs, I guess).

I’m just surprised a little bit that anyone would object to adding a little more historical information to a sign at a historical site. There’s no reason to complain, unless you’re so deeply racist that you resent any mention of the people the European settlers displaced to take over this region. Seriously, how can anyone be upset by this word?

But I shouldn’t be surprised. This cheerful message sparked a lot of online anger.

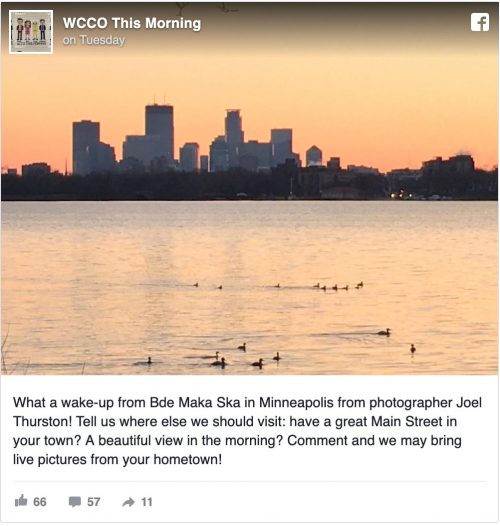

A great many white people flooded the comments to insist pointedly that that wasn’t Lake Bde Maka Ska, but Lake Calhoun, despite the fact that the name was officially changed. Calhoun was a Southern politician and vociferous advocate of slavery at the time of the Civil War, and it was totally inappropriate to honor him by naming a beautiful lake after him, but apparently some people think that it’s better to memorialize a white traitor who isn’t from this area than to use a pretty Dakota name that actually describes the lake.

If you’re wondering how it’s pronounced, it’s like it’s spelled. And that’s really what the lake is named on the maps.

OK, here’s Joe Bendickson demonstrating how to say it. Bendickson, by the way, has something in common with me: we’re both on Turning Point USA’s list of Dangerous Professors, which is entirely my honor.