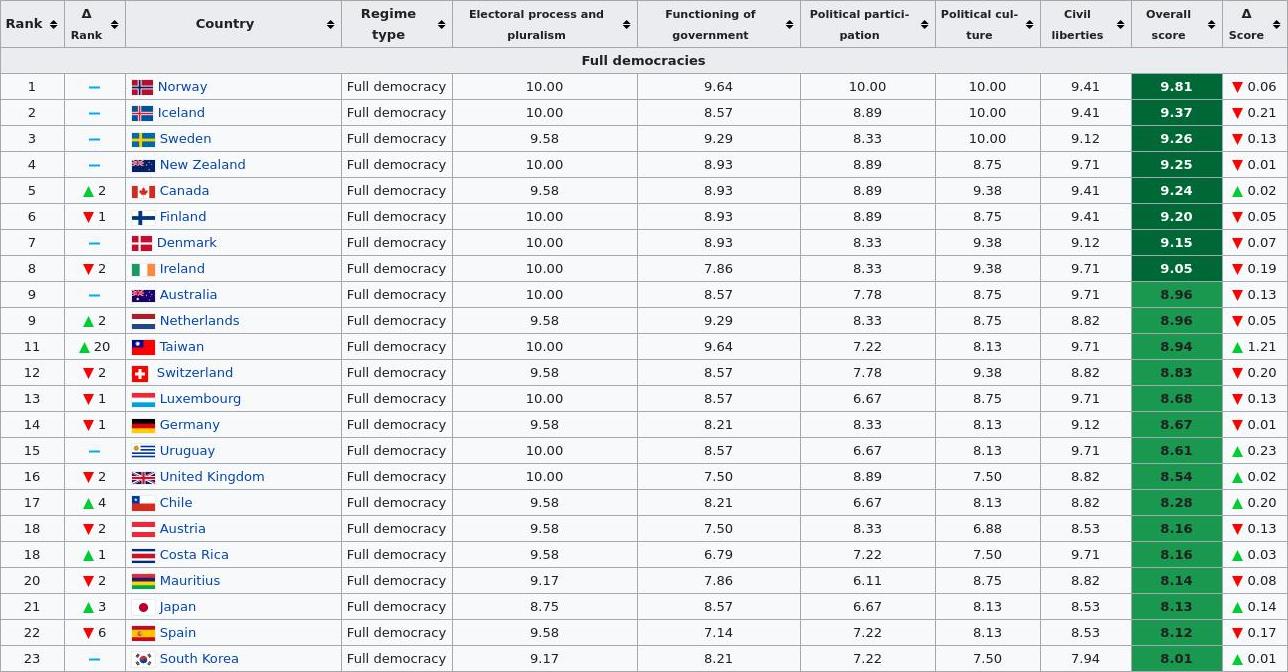

The Economist’s Intelligence Unit publishes its Democracy Index annually. They ask a group of experts to evaluate world’s nations on how democratic they are on a scale of one to ten (worst to best) based on five criteria:

- Electoral Process and Pluralism

- Functioning of Government

- Political Participation

- Political Culture

- Civil Liberties

from which they generate an overall score. The world’s worst is (unsurprisingly) North Korea at 1.08, and the best is Norway at 9.81.

According to the 2020 Democracy Index, there are only twenty three full democracies in the world. France and Portugal have fallen off the list, while Japan and Taiwan joined it. There are two each from North America, South America, and Oceania; three from Asia; thirteen from Europe; and only one from Africa, the tiny island nation of Mauritius. A significant number of countries have dropped in the rankings over the past five years where rightwing “populism” came into fascism. . .I mean, fashion. And least surprsing of all, many governments used the pandemic to violate people’s human rights and freedoms.

It’s not just democracy that sets these countries apart. With only the five exceptions named below, all 23 have three other things in common:

- Geographically small, under 1m sq. km of land (Canada, Australia)

- Population under 50 million (Japan 126m, Germany 83m, UK 68m)

- Secular societies

Countries which are geographically large or have large populations require larger governments and bureaucracies yet are harder to govern, making corruption much easier to hide and for individuals to perpetrate. It doesn’t surprise me that 21 of the 23 Full Democracies are among the 36 highest ranked countries on the Corruption Perception Index for 2020 (wikipedia version). There’s also a strong correlation at the other end: the countries which are most oppressive and most corrupt are the most religious, with oppressive communist (and officially atheist) states being the exception.

This is a screenshot of the Democracy Index from wikipedia, the numbers matching the EIU website’s index:

From Democracy Without Borders:

EIU report: In 2020, democracy declined worldwide amid pandemic

In the 2020 edition of their Democracy Index, the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) recorded the worst state of global democracy since the index was first produced in 2006.

Snapshot of global democracy

The report aims to measure the state of democracy in 167 countries, covering almost the entire population of the world and the vast majority of the world’s sovereign states. Using 60 indicators that collectively measure the electoral process and pluralism, the functioning of government, political participation, political culture, and civil liberties, it assigns each country a democracy score on a scale of 0 to 10. Based on their scores, countries are grouped into “full democracies”, “flawed democracies”, “hybrid regimes”, and “authoritarian regimes”.

In 2020, the average global democracy score fell from 5.44 in 2019 to 5.37, marking the lowest score in the index’s history. In total, the democracy scores of 116 countries declined, with only 38 improving and the other 13 stagnating. On a positive note, the percentage of the world’s population living in “full democracies” rose from 5.7% in 2019 to 8.4% in 2020 thanks to the improvement of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. At the same time, France and Portugal lost the “full democracy” status they had regained in 2019.

[. . .]

Impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic

The global health crisis caused by the novel coronavirus pandemic resulted in the largest curtailment of civil liberties ever undertaken by governments during peacetime. These restrictions, enacted in order to slow the spread of the disease and prevent further loss of life, were the primary contributor to the democratic regression seen in most of the world’s states, from “full democracies” to “authoritarian regimes”.

According to the authors of the report, the scores of many governments were downgraded because of the censorship of lockdown skeptics and other dissenting voices, the imposition of states of emergency and restrictions on civil liberties, and the general lack of citizen involvement in the processes that were used to make these decisions. [. . .] In many “hybrid” and “authoritarian regimes”, rulers took advantage of the pandemic in order to suppress dissent, subdue political opponents, and further solidify their grip on power. Contrary to past years, actions like these resulted in the largest democratic declines occurring in some of the world’s most authoritarian countries. In China, the pandemic led to an expansion of online censorship and surveillance, as well as a tightening of media controls and restraints on civil liberties. In order to control the spread of the coronavirus, similar steps were taken by other authoritarian governments throughout the world.

The rankings for several countries went up in 2020, despite the pandemic (Chile, Uruguay, Costa Rica, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan) while the openness of other governments’ about public health information (e.g. Australia, New Zealand, Mongolia) offset the reductions in personal freedoms. It proves that oppression wasn’t needed to deal with the crisis.