This article is part of a series discussing capitalism and socialism. Remember, the point isn’t to conclude that socialism or capitalism is good or bad. The point is to discuss which aspects are good or bad, and why. Don’t treat me as an authority, tell me how wrong I am, discuss.

Last time, I introduced the idea that labor has a certain maintenance cost, and creates a certain amount of value. The “surplus” is the difference between the value output and maintenance cost. In the discussion, we agreed that it’s difficult to define the productivity of each worker. Usually, many workers are cooperating to make the final product, and you may even have workers who are there to improve the efficiency of other workers.

There are two responses to this. One response is, even if we can’t define it on an individual basis, we can look at worker productivity and worker pay on a macro scale, and see that workers are getting paid less and less of the surplus.

Another response, is a question. In the current capitalist system, how do we evaluate worker productivity for the purposes of determining their wages? The answer lies in the idea of marginal productivity.

Image mine. Use with permission.

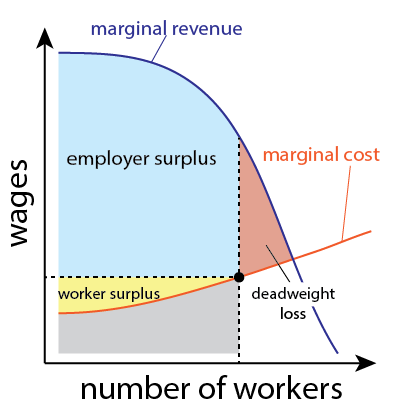

The above image is a standard graph, as might appear in an introductory economics course. I will take a moment to explain all the different elements, for those who are not familiar with such graphs.

- Revenue and cost are defined from the perspective of an employer (or group of employers). The revenue is how much money they make from selling products, and the cost is the bare minimum required to maintain the workforce.

- Marginal revenue refers to the change in revenue for each worker hired. Marginal cost refers to the change in cost for each worker hired.

- Under certain assumptions (e.g. perfect competition, substitutable goods), the wage and size of workforce tends towards the equilibrium point (indicated by a black circle).

- The worker surplus is the total number of wages paid to the workers, minus their total maintenance cost. The employer surplus is the total money they make from selling products, minus the total wages they pay to workers. The worker (employer) surplus is equal to the area of the yellow (blue) region of the graph.

There seem to be several parallels between this simple economic model, and the idea of exploitation of labor:

- The value of labor corresponds to the area under the marginal revenue curve.

- The maintenance cost of labor corresponds to the area under the marginal cost curve.

- The surplus corresponds to the area between the two curves.

- The distribution of surplus corresponds to the ratio between the employer surplus and worker surplus.

Of course, the correspondence between the simple economic model and the exploitation of labor model is not necessarily exact. For instance, in the theory of exploitation of labor, the maintenance cost of labor is equal to the cost of living. In the simple economic model, the marginal cost is not necessarily the cost of living, it could also include the opportunity cost. For instance, if there’s a soup can factory and a bread factory next to each other, the soup can factory has to pay enough not just to cover the workers’ cost of living, but also enough to persuade them to make soup cans instead of bread.

Now, let’s talk about the distribution of surplus. I drew the graph in such a way that the employers are getting the lion’s share of the surplus, although they do not get all the surplus. This is meant to be suggestive of what may be happening in reality. In this economic model, the distribution of surplus really has nothing to do with any concept of fairness (unless you define the outcome of the model as fair). It’s just determined by the steepness of those marginal revenue and marginal cost curves.

And yet, when I hear socialists complain about the exploitation of labor, I get the sense that they’re not just saying that the equilibrium wage is unfair. They also argue that employers wield political power to defeat the assumptions of the model, and push things in their favor. The simplest version of this, is that employers can exploit the cost of finding and switching to a new job, and become something like a monopoly to its workers.

A market with an employer monopoly (technically, a monopsony). Not to scale.

Under a monopoly, the total surplus is smaller (by an amount equal to the area labeled as “deadweight loss”), but the employer doesn’t care because their share of the surplus is larger. And the worker surplus gets smaller.

So, here we have two arguments: (1) The equilibrium wage leads to an unfair distribution of surplus, and (2) employers wield political power such that workers are paid even less than equilibrium wage. These arguments do not contradict one another, but there is a certain tension. On the one hand, we might emphasize the need to counteract the political power wielded by employers, to bring wages closer to equilibrium. On the other hand, we might emphasize that even the equilibrium wage is unfair.

Discussion questions:

- We defined surplus in the context of exploitation of labor, and also in the context of a graph based on a simple economic model. What are there differences between the two concepts, if any?

- To what extent do you think the exploitation of labor comes from an unfair equilibrium wage, vs deviation from the equilibrium wage? Do these two problems call for two distinct solutions?

Please feel free to question any other assumptions I’ve made, and also suggest future topics.

So. Here’s my impression of the reaction to this series:

Me: Socialism

Commenters: *50 comments*

Me: Okay, but let’s actually talk about economics.

Commenters: *0 comments*

haha interesting, there’s a future topic for you maybe 🙂

.

so personally i’m not very active in these sorts of conversations because i understand so little about economics, although i try (i puzzled over that graph up there for a while, i’m still not sure i actually got it right). and microeconomics always seems to come riddled with caveats (“assuming a rational agent…”, “under ideal market conditions…”) so i’m confused as to just how relevant these models are.

.

but anyway FWIW i guess i do feel that on balance yes, employers are too powerful, especially large companies and the state (though in different ways) both in setting working conditions (wages etc) within the workplace, and in setting labour policy state-wide.

.

but here’s another angle i like on this question of wages: in most companies, at least the larger ones, employers and managers tend to be paid way more than common employees. that doesn’t seem fair. i feel that in part at least, people who manage teams of people and take executive decisions do it because they enjoy that job. it’s not for everyone. in my ideal world we ought to do jobs that mostly satisfy us 🙂 so why should CEOs and managers also be paid (a lot, lot) more for their job??? i suspect that people whose only or main drive in being a boss is venality, probably don’t do a great deal of social good.

.

i mean ok, i haven’t given this a lot of thought, i’m just kind of personally disgusted at the sheer disparity between the richest and poorest people in the world, so reducing that gap seems like a good starting point? so, like i heard proposals for a 100% income tax above a certain figure, or a cap on maximum wage at 100 or 10 times the lowest wage in the company. i like those, especially the second one b/c it incentivizes paying all employees decently if the boss wants to increase their own salary.

.

but… idk, i guess if i was coding some parallel universe i’d define some kind of single hourly wage for *every*one? maybe a lot of bosses work long hours, so they would be compensated for that, but it would still be the same hourly wage, plus maybe some percentage extra for working late and for mental aggro or something. on balance you could maybe earn 2 times as much as someone working regular full-time, no overtime and doing not too physically or mentally taxing tasks.

so, would there be anything wrong with that? apart from that famous trickle-down thing, which, i mean, if you just share all the cash evenly from the get-go it doesn’t need to trickle down anymore right…?

.

hm. ok i am off-topic aren’t i?

@milu,

I don’t mind off topic so much, when comments are quiet. Also, I don’t think it’s off-topic.

You can construct (at least) two narratives of why CEOs get paid so much. Either you could say the marginal value of a great CEO is just that high, so companies are all competing to higher the very best CEOs. Or, you could say that CEOs have a lot of power to influence their own salary. I think the libertarian argument is that the first narrative is true, and therefore it’s “fair”, but IMHO it’s not fair under either narrative. Anyways, at least some economists argue for the latter narrative (see this comment), although I would not count on economists to agree on this point.

That sounds a lot like the labor theory of value which is a particular way of assessing the value of services/goods–usually associated with Marxist theory. Wikipedia describes it as a heterodox view, but even if the theory doesn’t describe real economic behavior, I feel like it’s a reasonable starting point to describing what a “fair” wage would look like. Certainly fairness doesn’t look like CEOs getting paid 100-1000 times as much as ordinary workers.

One complication is education and training. If I’m working at a job that requires a bachelor’s degree, then that implies some amount of labor to go through university.

@siggy

right, i cut my previous comment short because it already felt too long but i was going to add that for this to work out you also need free education, and while i was at it i was gonna throw in a bunch of other free or collectively-regulated ground-floor maslows like health, housing, basic utilities, transportation. meh im not sure this has much to do with economics though. that’s just… what a halfway decent society would look like to me!! the idea that some people are deprived of an education or unable to access medical treatment because they’re too poor??? god it just feels sooo wrong to me when there’s so much wealth to go around!!!

.

i guess the standard libertarian answer is “get a student loan, then factor in the cost of your education into your wages so you can repay that loan” but… i still don’t see *why* highly qualified jobs should be better compensated. presumably you become a maths teacher because you like maths, and for that same reason you will spend five years studying maths until you’ve learnt enough to teach other people. sure, you could’ve become a gardener and studied only two years, or you could be a seasonal farm worker and studied zero years. if neoliberal economists are right about human nature, and you’re paid the same regardless of how long you studied, suddenly everyone should just drop out of school and become seasonal workers and cashiers right!!!?? now that’s just silly. if you actually like maths, why would you mind spending five years studying maths? training for a job you enjoy is its own reward, it shouldnt have to be incentivized.

.

there is one objection i guess i don’t really know how to address, it’s what you maybe call the “scarcity theory of value”, i.e. the way the wage gradient tends to order people with rare and exceptionally useful skills at the top. (ideally.) (e.g. you @#3 when you talk about CEO earnings representing their marginal value and question the fairness of that narrative.) I mean whatever the political/economic structure, i think exceptional people will always be a thing. (put differently, there’s no reason for the distribution of demand and offer for any given skill to be isomorphic). but it seems that money is just a convenient proxy for that sort of sifting, and hopefully there’s other ways to get there. maybe prestige? i think prestige is pretty icky too but ok, maybe it’s a lesser evil. a non meritocratic culture, relying on radically remodeled or re-interpreted foundational myths and values might be a more satisfying but (even) less realistic answer.

.

final objection i can think up, the free education thing isn’t quite enough to counteract class privilege for a variety of reasons, but an obvious one is if your family is poor you’ll feel some pressure to get a job asap rather than study many years before you get one, especially if it’s not better paid. maybe universities could get students to start working part-time in the branch they’re studying from year one, and pay them for it, so the opportunity cost of studying vs. working right away isn’t quite so steep.

.

of course this is all cloud cuckoo land, not very useful in a pragmatic, strategic “where do we go from here” sort of discussion. (not to mention that all this is very very schematic, and like you said about CEO wages, it’s maybe(??) useful as a very basic starting point that would have to be amended and fine-tuned anyway for a billion reasons.)

.

(also, your link to Larry Hamelin’s comment was not working for some reason?? here it is again)

so, ok maybe all of this isn’t off-topic exactly, but i’m not sure how useful my contribution is to a discussion about the *actual* economic system.

perhaps partly because i’m economically semi-illiterate and don’t have a lot of patience for it, i do tend to veer off into idealism which while maybe interesting as a kind of reminder that any system is contingent and that Yes There Are Alternatives isn’t really what you had in mind for this discussion….?? nyeh

@milu #4,

I’m not sure I agree with that characterization of the libertarian view. I think the libertarian would say that well-compensated jobs are well-compensated, because that’s the compensation it needs to be in order to incentivize efficient allocation of resources.

Here “efficient allocation” means something like, sending the right number of people to college. As technology changes over time, educated workers produce more and more economic value–and here we’re talking about the value of their output, not the value of the input labor–recall that the “surplus” is the output minus the input. While some people might “enjoy” the kind of work that a college education lets them do, I do not believe that this enjoyment accurately tracks how valuable education is to our society. So if you want to improve the output of the economy, you might need to incentivize more or fewer people to get college degrees. And the way this gets incentivized, is by giving them a larger portion of the surplus.

But the thing is, even if incentives are necessary, they are not “fair”. If there’s a tradeoff between efficiency and fairness, how much do we value one vs the other? Or is there a way to have both? Are certain situations where a capitalist economy is both inefficient and unfair, and is there a way we can improve upon that? (These are rhetorical questions, I don’t expect answers.)

right, i think i see what you’re saying. there needs to be some kind of feedback loop that ties the cost of training to the production value of the trained workforce, so that the economy as a whole at least breaks even, and then some to invest in increasing overall efficiency. i mean, that makes sense.

anyway i’m in over my head, i don’t actually have anything useful to contribute. thanks for your patience though 🙂

Sorry, I’m full steam ahead going into finals week. I’ve just now read this post; I’ll think carefully about it as time permits. At first glance, everything looks pretty good. Your treatment of labor monopsony is simple, but for practical purposes it’s not too bad.

The wage, in addition to being a production cost, is also factor income: i.e. workers spend their wages. Therefore, second order effects are especially important: a higher wage will ceteris paribus decrease production (shifts both an individual firm’s supply curve and the short-run aggregate supply curve to the up), but the higher wage also increases demand (shifts individual firm’s and aggregate demand curves to the right)

I tapped my pocket economist for an opinion, and this is what he said:

After reading the comments, I want to add: I was taught, in something like Business 102, that a large part of the reason for high CEO wages was as a bribe to follow the law, instead of taking bribes from competitors and going where the law can’t follow you.

I don’t know the direction of causality between the marginal product of labor and the wage. In basic microeconomics, the wage and cost of physical capital (rent) are treated as exogenous. Companies adjust their mix of capital and technology based on those rates: they will buy labor and capital such that the marginal products of both are equal to the exogenous wage and rent. The constraint is usually a desired output level, but it is sometimes an actual overall budget.

Formally, given a production function F(L,K) and a desired output P, choose L and K such that we minimize the cost of labor and capital subject to the constraint that F(L,K) <= P. (I'm not sure how to type math here.) It's a pretty straightforward Lagrangian constrained optimization problem.

Normally, in perfect competition for labor and capital, an individual firm is a wage- and rent-taker; they cannot affect the wage or rent by changing the quantity they demand.

Wages and rents are probably set by the whole-market supply and demand for labor and capital.What determines those curves? I honestly don't know. Demand for goods and services for consumption are set by relative preferences; supply by physical constraints on production. But labor and capital are factors of production, not things to be enjoyed for themselves.

Not sure if this helps, but I have to get back to work.

This article might be helpful: On Karl Polanyi and the labor theory of value.

Quotations:

[T]he classical long term prices require that one distributive variable be determined beforehand. In other words, with real wages set at the subsistence level, something that was seen as historically and institutionally established in their time, the technical conditions of production (amounts of labor needed to produce, in the simplest version) were sufficient to determine normal prices. . . . In a sense, markets do not just appear out of thin air, in self-organizing fashion.