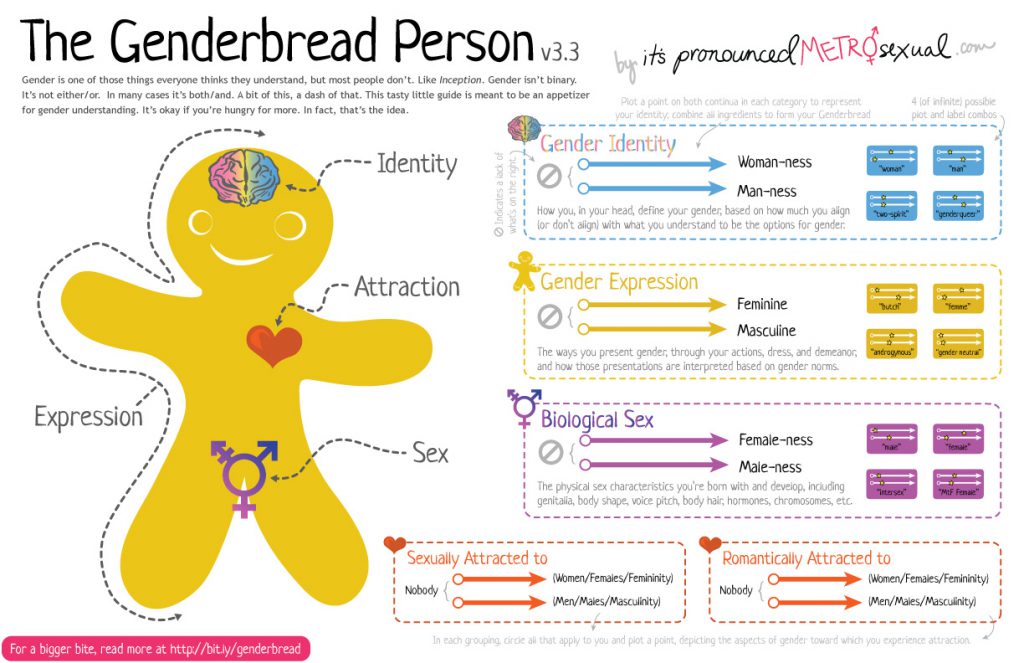

I’ve always been a fan of gender quotas. Think about it: sexism is largely unconscious and subtle, which means it has a disproportionate impact on subtle or indirect means of correcting gender imbalances. Blunt methods are more likely to succeed, and are more honest. If we truly think the genders are equal, why not bake that into our policies? Just be sure to incorporate non-binary people, too.

But there’s another good reason to endorse them. Emphasis mine:

Our study provides a unique window on quotas and, at the same time, pushes forward the measurement of competence in political selection. It uses the fact that, in 1993, Sweden’s Social Democratic party voluntarily introduced a strict gender quota for its candidates. In internal discussions of the reform, the party’s Women’s branch observed that some men were more critical than others. The quota became known colloquially as the “Crisis of the Mediocre Man,” since the incompetent men had the most to fear from an influx of women into politics.

If all genders are equal, but one gender has more representatives than the others, then by necessity there must be more mediocre members of that gender represented. Their average competence would be less than that of all other genders. We can measure that! And as yet another study found, quotas do indeed increase overall competence.

Within each local party, we compare the proportion of competent politicians in elections after the quota to the 1991 level. The figure below show some striking results. The left panel illustrates our estimates for politicians of both genders with black dots showing the change in the proportion of competent representatives in a party which is forced to increase their share of women (by 100 percentage points). The right panel splits the results by men and women (blue dots for men and pink dots for women). It shows distinctly that the average competence of male politicians increased in the places where the quota had a larger impact, and that the effect is concentrated to the three elections following the quota. On average, a higher female representation by 10 percentage points raised the proportion of competent men by 3 percentage points! For the competence of women, we observe little discernible effect.

Subdividing the men into leaders and followers reveals another interesting finding; there is clear evidence of a reduction in the proportion of male leaders (those at the top of the ballot) with mediocre competence. This suggests that quotas work in part by shifting incentives in the composing party ballots. Mediocre leaders are either kicked out or resign in the wake of more gender parity. Because new leaders – on average – are more competent, they feel less threatened by selecting more able candidates, which starts a virtuous circle of higher competence.

Embrace your inner socialist, and consider gender quotas. It’s good for business!