Now my brain is stuck on spider evolution, which is an awesomely cool subject, and how annoyed I am that creationists can spit on it with such ignorant contempt. So I have to mention another good article on the subject, Reconstructing web evolution and spider diversification in the molecular era. There are so many papers on this topic, and there’s a guy affiliated with the Discovery Institute writing a whole book on the subject while unforgivably ignorant of it all. So here, cogitate on this:

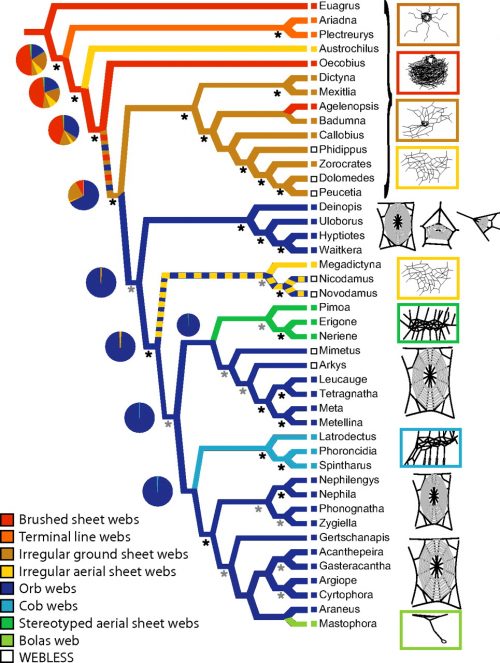

Optimization of web architecture on the preferred topology. Black stars indicate strong support for a node from both MP (jackknife > 75%) and Bayesian (posterior probabilities > 90%) analyses, and gray stars indicate nodes strongly supported only by one methodology or with jackknife 50–74%. Branch colors represent MP reconstruction of webs, and pie charts represent the relative probabilities from ML reconstructions. Colors of boxes to the left of taxon names represent their webs, and open boxes indicate that taxa do not spin prey capture webs.

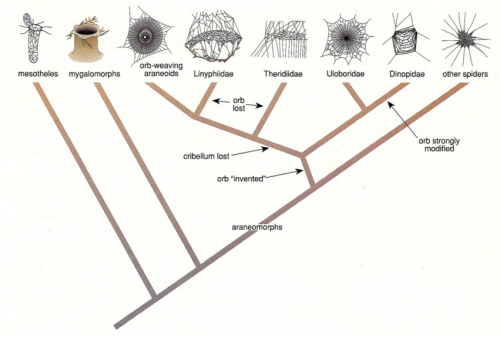

There’s also information on the topic of orb web monophyly that I mentioned in the previous post.

The monophyletic origin of orb webs is strongly supported, despite conspicuous differences in the silk used to spin different types of orbs. This has important implications for understanding both web evolution and spider diversification. Instead of cribellate and ecribellate orb webs evolving in parallel, orb monophyly explicitly implies that dry cribellate capture spirals were replaced by ecribellate gluey spirals. This involves 2 major changes. First, a shift in the silk used to produce the core fibers of capture threads, resulting in novel tensile properties. The core fibers of modern (ecribellate) orb weavers are composed of flagelliform silk, which is much more elastic than the pseudoflagelliform silk core fibers of cribellate spiders. Mechanically, flagelliform silk functions like rubber, relying on entropy to resist motion of silk molecules and absorb kinetic energy during prey capture, allowing the capture spiral to expand and contract repeatedly. In contrast, cribellate silk relies on permanent rupturing of molecular bonds to absorb kinetic energy and deforms irreversibly during prey capture. The second major shift involves the mechanism of adhesion, from dry cribellate fibrils that adhere through van der Waals forces and hygroscopic interactions to chemically adhesive viscid glue in ecribellate spiders. This results in webs with greater adhesion per surface area and may have facilitated the transition from horizontal to vertical web orientation in modern orb spiders, which is associated with increased prey interception rates.

That paper also discusses something I didn’t mention. Did you know that about half of all spider species don’t make prey capture webs at all? They’re active hunters, like wolf spiders and jumping spiders, and they belong to an extremely successful monophyletic group called the RTA clade, short for retrolateral tibial apophysis, the best band name ever.

I think I need to go spend some time in the lab with my spiders to cool my brain down, before participating in the podcast this afternoon, which will not be about spiders.