If you know anything about Robert E. Lee, it’s probably a mythic image, constructed by apologists for the Confederacy. He’s a heroic figure mounted on a horse, and at least in my head, his story is narrated in the honeyed voice of Shelby Foote, and he spins a story about a noble, courtly, gentle man, beloved by his troops, who only made the decision to lead the southern army because of his strong principles and love for his native Virginia.

He’s defended even now.

Nevertheless, I do not believe Lee deserves only censure and denunciation. I am not an expert on Lee, but to the extent I have read and learned about his life, I cannot object to the admiration many believe he earned as a man of dignity, honor, reserve, and duty. He was a devoted husband and father, an accomplished engineer for the Army Corps of Engineers, a hero in the Mexican-American War, a competent superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, and a man who earned the esteem of his contemporaries because of his competence, his accomplishments, his seriousness of purpose, and his overarching aura of personal dignity and honor. His superior during the Mexican-American War, General Winfield Scott, stated that Lee was ‘the very best soldier I ever saw in the field.’

That’s the standard myth. Maybe you ought to take a clue from the phrase I highlighted, and look to people who are experts on Lee. Maybe you ought to be suspicious when a human being is so thoroughly deified. This is why you have to respect honest historians, because they expose the truth. Lee was not a good man.

Lee’s heavy hand on the Arlington plantation, Pryor writes, nearly lead to a slave revolt, in part because the enslaved had been expected to be freed upon their previous master’s death, and Lee had engaged in a dubious legal interpretation of his will in order to keep them as his property, one that lasted until a Virginia court forced him to free them.

When two of his slaves escaped and were recaptured, Lee either beat them himself or ordered the overseer to “lay it on well.” Wesley Norris, one of the slaves who was whipped, recalled that “not satisfied with simply lacerating our naked flesh, Gen. Lee then ordered the overseer to thoroughly wash our backs with brine, which was done.”

He may have respected his men, but only when they were white.

Lee’s cruelty as a slavemaster was not confined to physical punishment. In Reading The Man, historian Elizabeth Brown Pryor’s portrait of Lee through his writings, Pryor writes that “Lee ruptured the Washington and Custis tradition of respecting slave families,” by hiring them off to other plantations, and that “by 1860 he had broken up every family but one on the estate, some of whom had been together since Mount Vernon days.” The separation of slave families was one of the most unfathomably devastating aspects of slavery, and Pryor wrote that Lee’s slaves regarded him as “the worst man I ever see.”

Reminder: the Father of our Country, George Washington, and his wife Martha, were also horrible people who kept slaves, but they weren’t quite as vile to them as Robert E. Lee. We praise them all with faint damns.

In summary, then, rather than the courtly gentleman, he was a terrible racist who treated human beings like animals. Worse than animals; we don’t condone abuse of farm animals, but he was a man who thought his black slaves needed brutal corrective discipline.

Lee had beaten or ordered his own slaves to be beaten for the crime of wanting to be free, he fought for the preservation of slavery, his army kidnapped free blacks at gunpoint and made them unfree—but all of this, he insisted, had occurred only because of the great Christian love the South held for blacks. Here we truly understand Frederick Douglass’ admonition that “between the Christianity of this land and the Christianity of Christ, I recognize the widest possible difference.”

But then he lost his war. He was ‘punished’ for his treachery by being allowed to return to private life, and was even rewarded by an appointment to the presidency of a university. Surely he was chastised and softened his views? No, that’s not how psychology works.

Publicly, Lee argued against the enfranchisement of blacks, and raged against Republican efforts to enforce racial equality on the South. Lee told Congress that blacks lacked the intellectual capacity of whites and “could not vote intelligently” and that granting them suffrage would “excite unfriendly feelings between the two races.” Lee explained that “the negroes have neither the intelligence nor the other qualifications which are necessary to make them safe depositories of political power.” To the extent that Lee believed in reconciliation, it was between white people, and only on the precondition that black people would be denied political power and therefore the ability to shape their own fate.

Lee is not remembered as an educator, but his life as president of Washington College (later Washington and Lee) is tainted as well. According to Pryor, students at Washington formed their own chapter of the KKK, and were known by the local Freedmen’s Bureau to attempt to abduct and rape black schoolgirls from the nearby black schools.

There were at least two attempted lynchings by Washington students during his tenure, and Pryor writes that “the number of accusations against Washington College boys indicates that he either punished the racial harassment more laxly than other misdemeanors, or turned a blind eye to it,” adding that he “did not exercise the near imperial control he had at the school, as he did for more trivial matters, such as when the boys threatened to take unofficial Christmas holidays.” In short, Lee was as indifferent to crimes of violence towards blacks carried out by his students as he was when they was carried out by his soldiers.

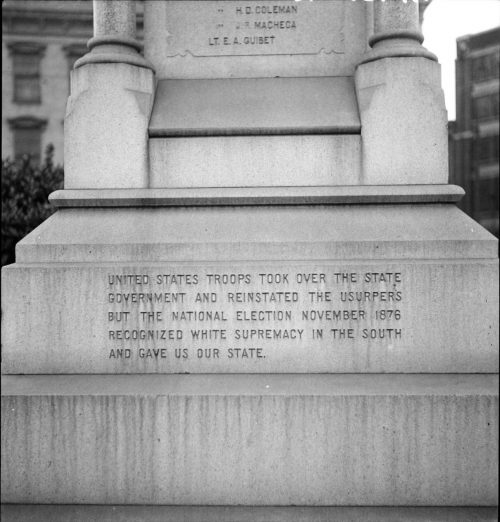

Why were statues erected to this bigot in the first place? There’s always the danger of lapsing into a Whig view of history, judging people by our modern enlightenment rather than the by the primitive standards of their own time, but this was a traitor who fought for slavery at a time when people were willing to fight a bloody war to end that oppressive institution, in which 2% of the population would die, which says that he was not simply a man of his time. It was also a time when the views of those black slaves were discounted, and they clearly thought he was a monster.

If you want to believe in a real conspiracy theory, here it is: defeated Southern leaders engaged in a successful campaign to rewrite the history books and venerate the villains in the Civil War, and they’ve largely accomplished their goals. They don’t say “Hail Hydra”; it’s “The South will rise again.” They also don’t whisper it to only their confederates; they shout it out loud, proudly.