It’s a sad story: the Niagara Falls Reporter was one of those urban weeklies that have been popping up all over the place in the last few decades. A good paper, apparently, with a lot of popularity…and then it was sold to a new publisher, a guy who dreamed of being Rupert Murdoch, perhaps, and it began to go downhill into teabaggery and censorship of the more liberal columnists. A movie reviewer, Michael Calleri, found his submitted reviews disappearing, strangely, so he asked why. The publisher wrote back and explained. It’s a long post with a long letter, but do not be daunted: it’s horrifying. The publisher did not like him reviewing movies with strong female characters.

I don’t want to publish reviews of films where women are alpha and men are beta.

where women are heroes and villains and men are just lesser versions or shadows of females.

i believe in manliness.

…

with all the publications in the world who glorify what i find offensive, it should not be hard for you to publish your reviews with any number of these.

they seem to like critiques from an artistic standpoint without a word about the moral turpitude seeping into the consciousness of young people who go to watch such things as snow white and get indoctrinated to the hollywood agenda of glorifying degenerate power women and promoting as natural the weakling, hyena -like men, cum eunuchs.

the male as lesser in courage strength and power than the female.

it may be ok for some but it is not my kind of manliness.

That’s just a short excerpt, and there’s much more. That guy really does not like women, except the meek and mild ones, and he hates movies that feature strong women so much that he doesn’t even want to know they exist.

He doesn’t even notice that in most movies, women “are just lesser versions or shadows of” men. I guess all we need to see in the future are more remakes of The Expendables (which so far I consider the very worst big budget movie of the decade.)

It also reflects something insidious. You can be a world-class idiot and regressive asshole and be filthy rich; there are economic niches, like, say, running a casino or a coal mine, where you can actually thrive with those characteristics, or even better, you can just inherit the wealth. And then what you can do is take over media and poison the intellectual environment.

The teabaggers know this. Christians know this. Look around you and you see it everywhere: there are so many lower level opportunities that can be snapped up and used to shape the culture: you don’t have to run for president or be rich enough to own Fox News. Run for school board, edit the local paper or entertainment weekly, charge into your regional political caucus and twist the agenda of your county. Conservatives are great at doing that, and if they don’t succeed in building something up, they’ll at least have destroyed a public school system or newspaper.

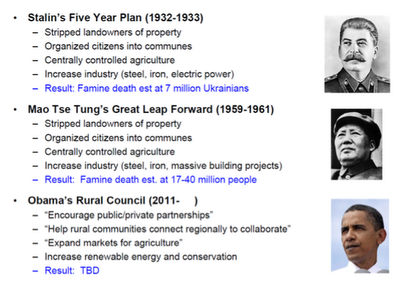

Look around your community. Stark raving lunatics can get positions of influence at the local level. And before you know it, conspiracy theorists and kooks are taking over your state, and instructing legislators on the finer points of madness:

Keep this in mind. We managed to get a conservative Democrat elected to the presidency. He’s going to be crippled because he has to work with a hierarchy of wingnuts.