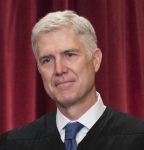

We have the receipts: Neil Gorsuch has a great big conflict of interest.

For nearly two years beginning in 2015, Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch sought a buyer for a 40-acre tract of property he co-owned in rural Granby, Colo.

Nine days after he was confirmed by the Senate for a lifetime appointment on the Supreme Court, the then-circuit court judge got one: The chief executive of Greenberg Traurig, one of the nation’s biggest law firms with a robust practice before the high court. Gorsuch owned the property with two other individuals.

On April 16 of 2017, Greenberg’s Brian Duffy put under contract the 3,000-square foot log home on the Colorado River and nestled in the mountains northwest of Denver, according to real estate records.

It’s not as if this was an attempt to curry favor with a judge presiding over big cases…

Since then, Greenberg Traurig has been involved in at least 22 cases before or presented to the court

Oh.

I guess when the process for appointing him was corrupt, you can’t expect a mere Supreme Court justice to behave ethically.