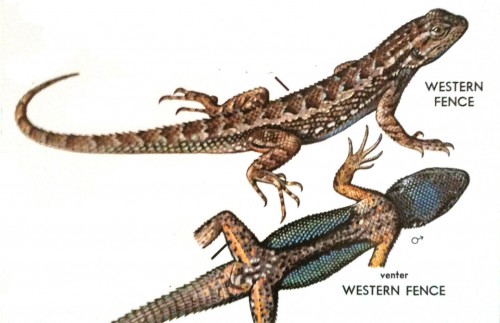

Western fence lizard, crappy phone camera shot from Stebbins’ Western Reptiles and Amphibians, Second Edition, painting by Robert C. Stebbins

One of the really cool things about being involved in the California Natural History Biz is that the science is pretty young. (In the sense of Western Science As She Is Peer-Reviewed, that is: people were studying nature in California thousands of years before it was called California.) The earliest years of plant exploration in California took place only in the late 18th century, the era of von Chamisso, of Douglas and Menzies. The California Academy of Sciences, the oldest natural history association in the Western US, was only founded in 1853 — at which point the Royal Society was older than the California Academy is now. Many of the big names in the field were working within living memory. Clinton Hart Merriam was still around in the 1940s, for instance. Edmund Jaeger, that most influential of California desert naturalists, only died in 1983, recently enough that I can feasibly resent never having met him.

I really resent not having met Bob Stebbins: we’ve talked on the phone a number of times, spent a couple of decades living within a few miles of each other, and he was kind enough to give me carte blanche to use any of his paintings in a local publication I used to edit. Missed opportunity: Bob is still around, but he’s moved from his long-time home in the Berkeley Hills to a convalescent setup in Oregon, and seeing as he has been exploring the world since March 1915, it’s understandable he doesn’t get out to socialize as much as he used to back when he was a younger man in his 80s.

Robert Cyril Stebbins has a list of publications longer than that of anyone else I can think of, but what he’s best known for is his Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians, an indispensible Peterson Field Guide for which Stebbins painted the color plates. He’s one of those frustrating people with consummate skills in multiple worlds when most of us struggle to do well in one at a time. Bob could easily have been a successful commercial artist if he hadn’t chosen to go for the big bucks as a herpetologist. He’s been officially retired from his professor job at UC Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology since 1978, which means that as of last year he’s been a professor emeritus longer than he was a professor nonemeritus: he started at the MVZ in 1945.

From his undergrad work to the present day he’s done as much to expand our knowledge of the California desert as anyone else, living or not, and he’s worked as much to protect that land as to study its herpetological inhabitants. He was among the people who worked to establish the East Mojave National Scenic Area, the BLM-managed precursor to the Mojave National Preserve, as a way of protecting its tortoises and other wildlife from the disruptions of industrial human society. He was especially active in working to limit off-road vehicle racing in desert wildlands, which up until the current explosion of utility-scale public lands renewable energy development was the single worst threat to desert landscapes. A bon mot from his testimony in 1987 before the Senate Subcommittee on Public Lands, National Parks, and Forests of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources:

“Permitting widespread ORV recreation in the desert is worse than allowing recreational chain-sawing in the nation’s forests. Forests potentially can recover.The desert probably cannot.”

I’m prompted to write about Bob Stebbins because he’s been doing some writing about himself, putting together his fieldwork memoirs starting at age 95. Herpetologist Matthew Bettelheim has been, with the permission and assistance of the Stebbins family, publishing sections of those memoirs in a running column on his blog. The short pieces are fascinating, a glimpse into the last century of California herpetological field work by a man who has been at the center of that work for most of that last century. Thanks, Matthew, for making them accessible to us.

And thanks, Bob, for putting them together.

not knowing the artist name but having much experience with the lizard pictured I have to say that the accuracy and detail is better than photographic. right down to the hard direct skeptical look being given by the little speeder.

uncle frogy

Nice piece and excellently interesting link.

From there, here‘s a nice little summary of Stebbins’s career.

I did meet him once; he was the guest of honor at a meeting of the Desert Tortoise Council and he signed some prints of his beautiful non-fieldguide paintings (tortoise, chuckwalla, collared lizard). They’ve hung in my offices ever since.

Frogy is right; his feel for the animals, developed over decades of firsthand experience and observation, really comes through in his paintings.

Please write about Bob Stebbins. I’d love to see more of his art, too.

(And I misread your title the first time around… Guess which part. :P I was surprised to see lizards featured in the image.)

This post is also some of the most blatant Petersonbait ever, I’m not sorry to admit.

Hanging on the wall behind my head right now, so that I can’t see it when I’m trying to work, is a print of his Desert Tortoise Matriarch painting from 1995, signed by the artist. House catches on fire, that’s second thing grabbed after the cat, and probably before my pants.

By the way, the California Academy of Sciences reports that there is a protein in the blood of the Western Fence Lizard which kills the Lyme bacterium. Ticks that have bitten a lizard have been disinfected.

http://www.calacademy.org/science_now/archive/wild_lives/fence_lizards_050601.php

I’m so sorry. So very sorry.

Definitely familiar with the genus Sceloporus. My lab studies their phylogeography. There’s an interesting hybrid zone outside of Flagstaff that we have samples from going back 40 years. We had as successful herping trip there in September. No occidentalis but plenty of other species.

Western Fence Lizard??? I’ve called these guys blue bellies since I was old enough to talk. Now, some fifty years later I find out that’s not what their really called! It’s like I just found out I was actually adopted!

I totally misread the title of this post and my nethers starting itching.

Kagato

At least you apologized in advance before I spit coffee all over.

I have a very delicate mummified Western Fence Lizard in a glass-front specimen case on my desk. (They get trapped in some of the underground vaults where I work and can’t get out.) Nothing but skin and bones…

got a crappy phone camera shot of that?

(I can’t find images of any of his paintings online.)

:)

Here’s the tortoise painting print, in as crappy a phone camera photo as I could manage:

That’s a painting!?‽?!

Apropos of nothing more than Californian wildlife:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/mec.12130/abstract