A week ago today a good-sized storm blew into Southern California’s desert off the Sea of Cortez, a.k.a. the Gulf of California. In the Salton Basin (a.k.a. the Salton Trough) north of the Gulf winds averaged 40 mph or so, with gusts above 60. The Salton Sea fills the lowest part of the Salton Basin and the winds churned that water, roiled up its murky, anaerobic depths, and released a cloud of stench, mostly hydrogen sulfide, into the air. People who’ve lived in the Basin are used to that smell, but last weekend the wind off the Sea of Cortez picked up that mixed hydrogen sulfide cocktail and blew it to Los Angeles. On Monday, air quality management districts got complaint calls from residents of Simi Valley, almost 200 miles from the Salton Sea.

It took a day or so before everyone agreed that the Salton Sea was to blame for the stench, and now a few more people are aware of the fact that it’s in trouble. There are plans to “fix” the Sea that would cost several billion dollars, which is getting no traction at all in Sacramento given rabid anti-tax sentiment in California. But “fixing” the Sea in the long term is futile, and the reason involves the Colorado River, plate tectonics, and — possibly — the Grand Canyon.

If it wasn’t for the Colorado River, the Sea of Cortez would extend well into California. Most of the Salton Basin lies below sea level, with only a 30-foot berm near Mexicali between it and the ocean. The Basin is a northern extension of the same rift that holds the Sea of Cortez, created by the north end of the East Pacific Rise as it works to splinter the west side of the North American continent. If it wasn’t for that 30-foot berm you could sail from Mazatlan to Coachella for the Music and Arts Festival, though you might need a snorkel to watch the Tupac hologram.

That berm is there because the Salton Basin/Sea of Cortez rift valley is where the Colorado River happens to reach the sea.

Rivers carry sediment, and desert rivers carry a lot of it, and over the years as the Colorado flowed into the Sea of Cortez rift valley and formed a delta, that delta gradually sealed off the Salton Trough from the open sea. Creating the Colorado Delta took a lot of sediment. As the East Pacific Rise wedges the rift valley wider, the valley floor drops. The Geology 101 term for a valley like this is a “graben,” German for “grave.” California has a few of them, including the valley currently occupied by Lake Tahoe. The floor of the Salton Basin has been sinking almost as fast as the Colorado can fill it up, so the Colorado must have had one hell of a good supply of sediment. More than 10,000 cubic miles of sediment, in fact. At Westmoreland, bedrock lies 18,300 feet below the surface. Even in the extreme north of the Basin the bedrock is usually beneath several thousand feet of sediment. That Tupac hologram stood atop about 13,000 feet of the stuff.

It’s been something like 5 million years since the East Pacific Rise started opening up the Salton Trough area, and if you ask yourself where the Colorado River might have found a lot of sediment in the last 5 million years, there’s an obvious answer that leaps up to suggest itself: 5 million years ago is a common estimate of when the river started cutting the canyons along its length, including that Grand one. That obvious answer is a little too easy: The Grand Canyon itself accounts for only about 1,000 cubic miles of potential sediment, and there’s some thought its carving may have begun significantly before Salton Trough formed. That’s okay. The Colorado’s watershed is about a quarter of a million square miles, so there’s a lot of arid land to provide sediment.

The Salton Sea was formed in 1905 when a would-be agricultural promoter with more enthusiasm than sense dug a canal in some of that sediment from the Colorado River to the Imperial Valley in the Salton Trough. A flood surged over the canal’s headgates and flooded hundreds of square miles of desert. If left to its own devices, the resulting lake would have dried up by the 1950s or so, but almost one and a half million acre-feet a year of agricultural and urban runoff has kept it full. That runoff has been chock-full of nutrients, including ag fertilizer and silt but also including sewage from the New River, a channel between Mexicali and the Sea that until recently was considered the filthiest river in the US, so full of pathogens and industrial chemicals that technicians wore hazmat suits to take water samples. (It’s a bit better now.)

Despite the pollution, the Salton Sea isn’t dirty so much as overfed. The Sea has no outflow other than evaporation, so everything soluble that’s entered it is still there unless it can volatilize and blow away like hydrogen sulfide. The water is so nutrient-rich that massive blooms of algae appear, grow, and die, consuming the dissolved oxygen as they decompose. Sometimes only the top few inches of water have any oxygen at all. Tilapia were planted in the Sea in the 1950s, and on bad days you can watch them gasping at the surface. Then they die, and wash ashore, and botulism sometimes breaks out in seabirds that eat them. This is a big problem, as the Sea is a crucial spot for migrating birds: more than 400 species have been noted there.

The Sea has been declining for a while, and in 2017 it’s going to take a nose dive. In 2003 the local Imperial Irrigation District agreed to send a lot of water to San Diego for people to water their lawns with. Sine then, farmers supplied by the IID have been switching to drip irrigation, fallowing their lands, and in general giving up less water to the Sea. Since 2003 the Sea has shrunk by 14 square miles. IID has been putting “mitigation water” into the Sea, but in 2017 that stops. If nothing’s done, the Sea’s fish will probably die out within a year or two. For a few decades after that the Sea will continue shrinking, until it’s a hyperalkaline body of water 29 miles long and 14 feet deep that periodically belches out clouds of hydrogen sulfide. It will still be biologically productive, but that food chain is going to be short: bacteria, algae, brine shrimp and flies, and a few birds that eat flies.

The state of California is considering plans to preserve some of the Sea’s habitat. The most-discussed scenario involves diking off some marginal sections of the Sea, maintaining open water habitat at either end, and letting the vast middle dry out. This scenario is not uniformly popular with people who live nearby, because giant clouds of alkaline dust in the air can ruin your day, not to mention your lungs. In any event, it will take upwards of $5 billion to carry out that plan, and California isn’t likely to throw that kind of cash at an environmental restoration project anyway.

Doing something to maintain habitat would be a thoughtful interim measure for the birds, but it would essentially be a bandaid on a long process we’re unlikely to control any time soon. The Salton Sea isn’t the first body of water that’s been there. At least three times before, the Colorado has changed course to flow northward into the Salton Basin, filling it up. The PaleoArchaeo folks call these previous, much larger iterations of the Salton Sea Ancient Lake Cahuilla, and I’ve been out in the open desert forty miles from the current Sea and found evidence of pre-contact settlement and fishing camps atop what were once lakeside hills.

And then the Colorado would shift course again, and the old lakes spent a few decades dwindling, growing hypersaline, losing all their habitat and turning into alkaline desert flats.

Those lakes were just a small part of a much larger, dynamic system that encompassed the entire Colorado Delta. When Lake Cahuilla dried up because the flow of the river had shifted, that loss of habitat was mitigated somewhat by the creation of new habitat at the river’s new mouth. What makes the death of the Salton Sea different from the deaths of previous lakes is that we’re not leaving any replacement habitat. The Colorado’s outflow delta is moribund. The river no longer reaches the Gulf except in very wet years. Every single drop of it has been allocated to one use or another. Over the last century we’ve built dozens of dams on the Colorado and its tributaries to regulate the river’s flow. They also function as giant silt traps. The Colorado got its name from the reddish sediment it used to carry: since the dams went up, the Colorado is usually a deep blue-green. The floods and silt that maintained the Delta’s habitat are gone.

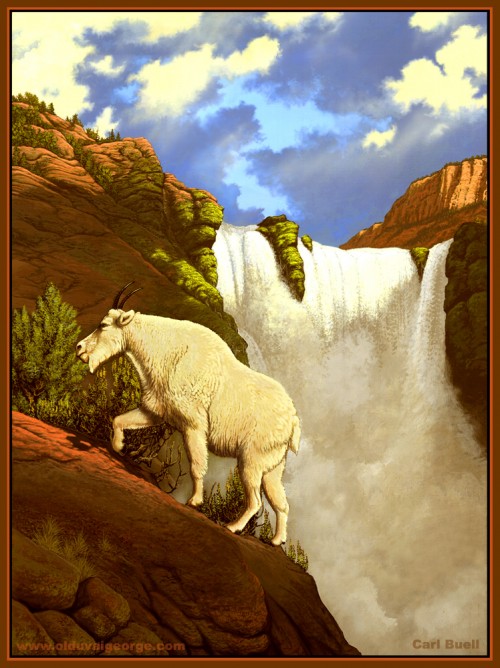

The Colorado has taken out much more impressive dams than we could ever build, starting about 3 million years ago when volcanic eruptions blocked the river, creating dams of solid lava as high as 2,000 feet like the one Carl Buell rendered here with a Harrington’s mountain goat.

The largest of these dams created lakes that took as long as 3,000 years to fill. They may not have taken very long to empty: there’s evidence that some of these dams failed catastrophically. Imagine a 2,000-foot dam failing all at once, and a 300-foot-high flood racing downriver. We almost had a small replay of that drama in 1983, when Glen Canyon Dam nearly failed during a mere 25-year flood. If it had gone, the flood would almost certainly have overtopped Hoover Dam, possibly taking it out too, and the combined floodwaters of Lakes Powell and Mead would have barreled down on the dams in the Lower Colorado. It didn’t happen, due to some plywood sheets the Bureau of Reclamation nailed up atop the Glen Canyon Dam, but eventually it almost certainly will — and the sediment will flow again. Nature bats last.

The trick is to keep the Delta’s wildlife alive in the meantime, whether on the Salton Sea or somewhere else nearby. It’s not even close to certain that we’ll succeed.

Have they tried nuking it? That would kill all the C. botulinum, and burn off the hydrogen sulfide.

There would be one or two minor drawbacks to that plan.

Awesome article. Too bad I have to nitpick. “Graben” means trench, ditch or canal. “Grab” would be grave.

This was very readable and entertaining introduction to a subject I knew nothing about. I look forward to more in this vein.

Though the general topic of “ecological woes” might be unending and depressing. Perhaps some conservation success stories as chasers?

Nitpicking is what primates do, lasius. And thanks — the “grave” explanation is in a whole lot of printed matter, and I wonder if it isn’t one of those fox-terrier-sized hyracotherium oral tradition” things.

Oh, for sure, or at least natural history. If you think it’s downbeat to read these, imagine how it is to write ’em.

Thanks for this, Chris. I’d been under the impression that the Salton Sea had been around for far longer than 1905.

Too many people don’t understand this point.

Excellent article Chris. But you know what “they” say… “In California, liquor is for drinking and water is for fighting over.” Saving the Salton Sea is just another excuse for a fight. One that never gets won by anyone in this parched state.

I’ve read various histories of the Salton Sea over the years, Chris, but yours is simultaneously the most informative yet accessible. Thanks!

Love this.

Wonderful, enjoyable article.

Re the “graben” issue, modern meanings aside, what is a grave other than a trench or ditch with a specific purpose? “Grave”, “Grab” and “Graben” all come from from PIE root *ghrebh- “to dig, to scratch, to scrape” (thanks to the online etymology dictionary).

That said, the printed matter is definitely confused, and wrong, if it says “Graben” means “grave” in German. Lasius is absolutely correct.

When I retire I want to buy a beat up RV (must be less than $500), and move to Slab City next to the Salton Sea. I hope it’s still there. I love watching the videos.

Check it out!

I had to blow that “on the shore” picture way up to see what was in the background — barnacles! How the heck did those get there, since the lake is artificially created and landlocked?

I know I’m late to the party and others have shared similar sentiments, but your easy-going and humorous style makes your writing a delight to read, Chris Clarke. There’s a cadence to your writing that really resonates with me.

“Most of the Salton Basin lies below sea level, with only a 30-foot berm near Mexicali between it and the ocean.”

It would necessitate giving up a few towns, but I think the best thing would be to do a hundred meter wide cut through that 30-foot berm and let the Salton Sea become an extension of the Sea of Cortez.

some thoughts on the Salton Sea.

What with the value of the real estate that would be down wind of the dust emitted from the dried dead bottom of the Salton Sea and the residents of those areas suggest that the state will probably do something to at least mitigate the problems caused by the dust?

how far is the sea of Cortez? would it be any more absurd to dig a channel to reconnect it with the sea than the creation of it in the first place?

uncle frogy

What a fascinating and detailed post! This made me really curious about the 1983 events at the Glen Canyon dam, so I found a documentary video about it online:

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-1358563539762136744

That was my thought.

IIRC, the sea of Cortez has quite a tidal bore. That would keep things from becoming anoxic. You could even put in a barrage tidal power plant.

Apparently the tidal bore is no more because the Colorado no longer flows into the sea. But the tides are still there.

Must be some obvious reason. Maybe Mexicali doesn’t want to be underwater or something.

@11 Trebuchet

“barnacles! How the heck did those get there, since the lake is artificially created and landlocked?”

I would guess birds.

If California Gulls can get to Utah, the Salton Sea would be a piece of cake.

Excellent informative article.

Thanks Chris

Salton Sea does indeed have barnacles, Balanus amphitrite, which were introduced to the sea during World War Two, some say via seaplanes landing on the lake. Otherwise by boats. Slab City, mentioned above, is the site of a former U.S. Navy base.

By 1949 people were already suggesting the Salton Sea population of barnacles had diverged sufficiently from its parent stock to be considered a distinct subspecies, Balanus amphitrite saltonensis. Which is kinda cool.

profpedant, you probably don’t need to dig that ditch. Five-meter high tides aren’t at all rare at the mouth of the Colorado, and the Sea is in tropical storm country: add a good storm surge and a couple feet of sea level rise to a spring tide and the ditch might dig itself.

This has got to be the best short article on the Salton Sea I’ve ever read. And thanks for the current events angle – I didn’t know about LA gettin’ all upset.

unclefrogy-

Real estate value is always a self-dooming thing. People build where they really should not. But mostly the products of development, and further development, lower the value of previously developed areas. Never mind the market games and artificially inflated value of real estate in the first place in our systems.

F

I was thinking of mostly who are the property owners out that way.

They can employ layers and lobbyists it is not a farming area though there are farms a plenty out that way. I was thinking of the winter homes of the rich and famous, but what do I know, the same class of people managed to get the air traffic at john Wayne airport modified to suit those that live in New Port Beach.

just thinking out loud

uncle frogy

Ever since I learned about the Salton Sea, I’ve been intrigued with the idea cutting a trench to the Sea of Cortez and letting it fill. I suppose that’s because I’m of an age that I grew up reading Willie Ley’s articles about geoengineering. It never occurred to me how long filling it would take. I always imagined, BOOM, we open the flood gates and it would be full in a few weeks or months. Considering it would take years, possibly decades to fill, quite a bit of power could be generated on the slope of the canal.

unclefrogy

Although the smartest time to start planning to refill the lake is about ten years ago, you’re right about the rich lakeside homes being the biggest barrier to doing anything at all. Politically, the best time to do something will be around 2020 when the rich and influential will have experienced several seasons of toxic alkali dust storms. At that point, they will be open to the idea of the state buying them out.

The best tasting tilapia our family has ever had came from the Salton Sea in the mid 90’s. Maybe it was because of all the pollution and such…

It seems to me that whenever humans try to fix nature, we get neutered instead.

It wasn’t mentioned in the OP, so I assume the H2S concentration is low enough to not be particularly dangerous. That’s some nasty stuff, being both toxic and flammable, and IIRC (too lazy to look it up) it’s heavier than air and pools in low lying-areas

damn. hyphen fail. Low-lying areas. My bed is a low lying-area, being a just a mattress on a low frame.

“Five-meter high tides aren’t at all rare at the mouth of the Colorado, and the Sea is in tropical storm country: add a good storm surge and a couple feet of sea level rise to a spring tide and the ditch might dig itself.”

Oh ho! That could make for some excellent television disaster/storm reporting! Unfortunately excellent disaster/storm reporting comes with quite a few expensive externalities, the maritime flooding of the Salton Sea would probably be a lot cheaper with an intentionally dug canal. Less dramatic though, so lower ratings. (Although a canal large enough for a grey whale could ultimately produce some nice footage.)

profpedant

A grey whale in the hydroelectric turbines might might make for some good news copy–“A whale of a problem at the Chris Clarke power plant, but first, some damn Kardashian or another in a skimpy dress”–but it would be an expensive mess.

It seemed obvious enough to dig a canal that it’s been thought of many times before.

1. The distance between the Salton sea and the Sea of Cortez is 185 km.

2. The highest point between is 100 feet. It’s all flat alluvial fill.

3. Alluvial fill is easy to dig up and move.

It was described on one website as a large but not that difficult a civil engineering project.

There really isn’t any engineering reasons not to dig the Mexicali-Salton sea canal.

The problems are all political and economic. Much of it would be in Mexico. OTOH, the entire Suez and Panama canals are ex-USA and that hasn’t stopped them.

I was not very clear the real estate I was thinking was the real estate down wind mainly Palm Springs and environs. I have seen projections of the dust plume and it goes right down the middle of that valley dust full of toxic minerals and fungus. There is a similar big problem with that in the “Owens lake” area that is costing a lot right now. It would be the ones with houses by the golf courses in Palm Springs. They are the ones who will complain the loudest and would have the most influence with Sacramento and Washington not the trailer courts down by the “Sea” .

uncle frogy

@profpedant: “It would necessitate giving up a few towns, but I think the best thing would be to do a hundred meter wide cut through that 30-foot berm and let the Salton Sea become an extension of the Sea of Cortez.”

It would also necessitate wiping out one of the most productive agricultural areas in the country. The Imperial Valley is a huge part of why vegetables remain cheap all winter long.

We’d lose more than just a few towns. I live directly north of the Sea, on the other side of Joshua Tree NP. If you look, right in the middle of the business district of Indio, there is a sign saying Sea Level. We stand to lose a huge agricultural area, and hundreds of thousands of homes and businesses. A big part of Interstate 10 is below sea level before you start climbing east of the Coachella area. Nasty mess to clean up.

Hmm..100 ft drop and a need for a rationed influx of sea-water. Why not build construct a hydro-electric / partial fill system, instead of just a ditch? Cheap electricity and save the lake. Not an engineer, don’t know the environmental consequences, but it seems doable.

And what would the impact of all the agricultural sediments that are now in the Salton Sea, once they get to the Gulf of California? Not GOOD, I am thinking.

Further checking shows me the error of my guess about barnacles hitchhiking with birds, so that’s not likely how they got to the Salton Sea, and the plane/boat path mentioned by CC is obviously the more reasonable explanation.

However, my investigation did turn up an unusual side effect of bird-banding I hadn’t heard of before:

“The presence of adult barnacles of Fistulobalanus pallidus (Darwin) and Fistulobalanus albicostatus (Pilsbry) attached to field-readable plastic leg rings on the Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus in Northern Europe is reported. … This may pose a new and wholly unexpected transportation pathway for barnacles as invasive species.”

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20544434

Barnacles hitching on plastic rings … nature will find a way.

Is there a seaweed that grows there? If so why not farm that and then take it and use is as organic matter (and fertiliser) on soils ravaged by modern farming.

Or possibly run a power plant on the seaweed and then return the nutrients to the farms upstream.

If you are interested in the “creation” of the Salton Sea, there is an interesting Book “The Salton Sea” by George Kennan (McMillan 1917). You can download it free in PDF form from Google Books. It describes some of the politics and thoughts in the Imperial Valley at the time.

Also, if you are in the Yuma, AZ area, just west of Yuma along the Colorado River, you can still see some of the old railroad track that was laid there for the railroad to bring in material to close the breach in the canal that was the cause of the “disaster”.

Oh, and if you’re really interested (like I was a couple of years ago), there is a silent movie with Gary Cooper from 1926 called “The Winning of Barbara Worth”. Not quite factual, but interesting to get an idea about the times.

Great post. I’d heard the name “Salton Sea” but knew nothing about it.

Reading the many, sensible eco-engineering solutions being mooted in these Comments saddens me.

Our political masters in the forseeable future (ie either right or left – usually down and back, never up and forward) are hardly likely to adopt such proposals.

I am not seeing anything more than guesses as far as the geoengineering goes, and as posts 32-33 show, there are really big unintended consequences from even those. There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch is a central organizing principle of the universe and we would do well to remember that when proposing large scale projects like this.

That isn’t to say that we should do nothing, or that those who are speculating are doing something stupid. We just need to be careful and realize that if something could be done on the cheap, it probably would be already underway.

Such as?

#43 “if something could be done on the cheap” it would be opposed at the highest level by those with a more expensive, stream generating scheme designed to soak up as much public funding as possible.

A siphon, with electric generating capability, might work and would be controllable – the only downside would be the cost, if it were shut off quickly.

Comments 3 and 9 are right. Although the words are obviously related, “grave” is Grab, and Graben is “trench”, “ditch”. The verb graben means “dig”.

~:-| Is that how the term is used in English? I thought it was the line that sheds, divides/separates, the area drained by one river from the area drained by another. The Continental Divide would be a watershed that way.

Same in German: Wasserscheide, where scheiden is obsolete/literary/poetic for “separate”. This being Pharyngula, I’m obligated to derail this thread by pointing out that Scheide also means “sheath” – including “vagina”.

…which would be awesome.

Yes yes yes!!!

This has also been proposed for the Qattara depression in Egypt. The fun thing about that one is that evaporation is so high there that it would never fill up (till the next climate change).

As long as you can still smell it, it’s not dangerous, at least not acutely so.

Hydrocyanic acid is just as toxic; but your nose is much less sensitive to it. When you can smell it, it’s almost too late.

If anyone wants to track the history and current status of what has been proposed for the Salton Sea, they can check out the website for the agency “tasked” with the project.

and yes, that’s right… nearly 20 years since the authority was formed to propose and enact a solution to the problem of the Salton Sea.

IIRC, it was originally formed in 1993.

@46 – “Is that how the term is used in English?”

Easy enough to find out:

http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/watershed

You’re thinking 1a, he’s using 1b:

b : a region or area bounded peripherally by a divide and draining ultimately to a particular watercourse or body of water

oh, forgot the link :P

http://www.saltonsea.ca.gov/

….and also forgot to thank Chris for putting this article up!

I’ve kinda lost track of the issue since leaving the area for Hobbitton.

That’s really interesting about the barnacles!

@#35, Pipenta:

Chris, I’ve never understood why anyone (except the handful of desert rats that live there) cares about saving a man-made lake that often stinks to high heaven and poisons birds. But I guess that what you’re saying is that the SS took up some of the slack when the Colorado dams destroyed bird habitat, right?

@johnmarley:

First, no, H2S is not heavier than air (MW = 18, typical air at STP = 28.8). Pooling in depressions isn’t an issue, and at these low concentrations buoyancy isn’t particularly influential — H2S behaves as a passive scalar.

Preliminary sampling results (more at the link, just a few illustrative numbers here) from the SCQMD:

So yeah, it looks like in some regions there could have been human impact problems beyond smell, though I would doubt too many people were exposed to dangerous levels. Important to stress that the sampling data is “instantaneous” and not averaged, and that proper QA has not yet been done.

To put those numbers into perspective beyond the state standard, here’s some lazy wiki sourcing:

And definitely,

By the two-headed goat of fail, I have completely misrepresented those numbers. The threshold levels in the wiki link are in ppm while the reported levels are in ppb. Can’t believe I made such a stupid unit mistake. /flogs self

So yeah, definitely no real human health concerns beyond odor.

Err … wouldn’t that hump in the middle get in the way, being somewhat higher than 10.1 m. Or were you planning to use part of the electricity generated to pressure the water input and get over the hump that way?

Geez… Sulphur has sure gotten lighter – or else Hydrogen gained negative atomic mass.

And it happened in my lifetime :-)

Great to see a geology-related article. Coming from the UK I knew little about the Salton Sea.

However, I believe I know something about chemistry and chemical safety and some of the comments may be incorrect. Thus:

The molecular weight of hydrogen sulfide is 32.08 i.e. slightly more than air.

Hydrogen sulfide does collect in areas with limited ventilation and is a particular hazard in “Confined Spaces”.

As far as smell is concerned:

OSHA Fact Sheet on Hydrogen Sulfide

”Human Health Effects from Exposure to Low-Level Concentrations of Hydrogen Sulfide” Simonton and Morgan Spears • October 2007

I would guess that you live next to a long term source smelling of hydrogen sulfide at your own risk. The usual high risk groups (babies and the elderly) will be at particular risk.

Getting closer than the MW = 18 from #53 PatrickG . Hydrogen with ca. 0.008 atomic mass does the trick :-))

If the Salton Sea is artificial to begin with, owing its existence to an accident with an agricultural canal, why work so hard to save it? Wouldn’t letting it dry up completely solve the anaerobic bacteria problem?

That is simply impossible. Any power generated by running down a slop is equal to the power required to pump the water up an identical slope …assuming 100% efficiency. Since this assumption can not be met in reality, there would be a net loss in generation, rendering the whole process futile unless that ‘hump’ is removed. Any hydroelectric system would have to cut through or avoid that hill to remain useful.

I’m curious on another aspect of this proposal: any attempt to carefully fill the basin from the sea would surely be at terrible risk of uncontrolled flooding should anything go wrong (earthquake, cyclone, earthquake + tsunami) at the inlet.

By the way Chris, this reminds me of a (tangentially) similar situation in my home state of South Australia – the mouth of the Murray River, currently facing the same fate already suffered by the Colorado Delta. Naturally, politicians from the upriver states refuse to lift a finger to do anything about it. No rush… only one of the coolest lagoons ever depends on permanent dredging to stay alive. The Coorong lagoon: about 100m by 130km, separated from the sea by a glorified sandbar, surrounded by dunes and succulents, home to 3.2 metric shitloads of birds. A bit distant to visit perhaps, but damn pretty.

I have a little trouble worrying about an ecosystem that is only 105 years old and artificially created. Yes, there is the concern is primarily for its effects on the people around it. But is the net effect of saving this sea that much different. Not only are there the sacrifices in terms of money and water use that have to be made, but isn’t the sea headed the way of the Great Salt Lake in the long run regardless?

The delta isn’t necessarily dead! Here’s a source I re-found quickly: http://www.hcn.org/issues/188/10000/print_view

Some others I can’t find again so quickly also pointed to the possibility of regenerating the Colorado’s ultimate delta with the sea, with relatively little effort, at least to avoid the worst kinds of environmental outcomes possible…

I have a little trouble worrying about an ecosystem that is only 105 years old and artificially created.

you don’t understand.

this ecosystem ended up buffering the tremendous damage that has been done to the ecosystem that comprises the colorado river delta area north of the Sea of Cortez.

It is important to a great many species.

ignorance is not your friend.

It’s really irrelevant how old it is or how it was once artificially created (by the way, it wasn’t artificially “created”, it arose and evolved naturally after a triggering event that happened to be artificial – there’s a difference).

What matters is what it is like NOW, and what the consequences of its destruction would be NOW.

105 years is plenty long enough for lots of ecosystems to establish themselves.

True, but you forgot something.The Salton Sea is lower than the ocean from which the water will be pumped.

The hill would still have to be avoided or ploughed though, rather than going over it.

Not that it really matters, chatter here is useless when the powers that be have no interest.

Is it low enough to make up for the inevitable inefficiency and energy lost from the upward pumping?

When the Red-Dead-Med project was being bandied around, it was considered that a net gain in energy would be obtained. But then the Dead Sea is more than 300m down!

Why would you think that? The water company where I live has no problem pumping water to the tower on the hill-top behind my house.

Because loose ends should always be tidied – for posterity’s sake :-))

Eons hence, when future archeologists sift through the remnants of our long forgotten civilization, perhaps they will recover fragmented records of this conversation, and will be tricked into thinking “so they were thinking about trying to fix the problem, a pity that they ran out of time” rather than “ha ha, what short-sighted fools, to have twiddled their thumbs while their doom came upon them.”

I hope you are wrong, but I fear you are right. If they get tricked, they could repeat our mistakes. Like us, they could learn from history that people learn nothing from history.

I’d say pump the lake out and rebuild the Colorado Delta.

But up here by SF farmers in the inland valley were clamoring to take the water feeding the delta here… Because of the drought, doncha know. Nevermind they can just plant their crops again next year but the smelt – which feed our fishing industry, btw – won’t survive if they take all the water.

I totally don’t understand the amount of self-centeredness and lack of awareness that would allow someone to take so much that something would be permanently damaged. Even when we have evidence of what that damage does! It’s taken us decades to get our fishing industry out here back to the point that it supports anyone – and they want to kill off the fish permanently.