I think this little vignette is totally staged — a Fox reporter would never be that honest and open.

Fox News reporter gets very candid about vaccines.

Made by @jpscattini pic.twitter.com/kMHdCIpAPx— Walter Masterson (@waltermasterson) July 25, 2021

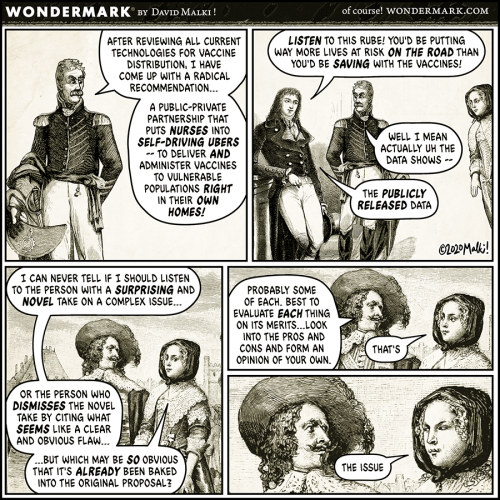

I think a Fox or OAN or Newsmax person would actually take an approach like the supercilious fop in the second panel of this cartoon.

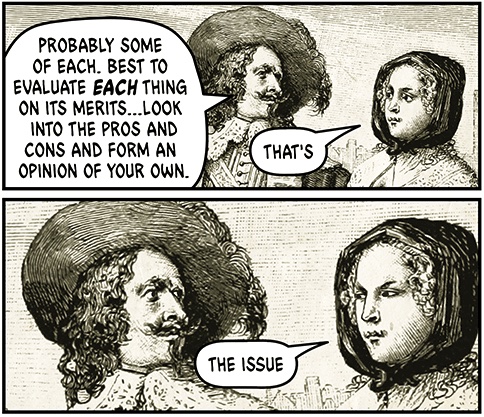

They’re not stupid. They’re venal and short-sighted, but give them some credit — they’ve got a well-paying job and an opportunity to air their vanity on an international broadcast (you know the ones who aren’t too jaded are calling their family to let them know “Mom! I’ll be on a 3 minute segment this evening explaining how the Reptoids snuck toxins into the vaccines!”). They’re not going to throw that away. They’re going to just cycle through semi-plausible excuses and made-up data to rationalize their bad takes.

What I found most interesting about the cartoon is the last two panels. The guy in the big hat is well-meaning and echoes a sentiment I’ve heard a lot.

Best to evaluate each thing on its merits…look into the pros and cons and form an opinion of your own.

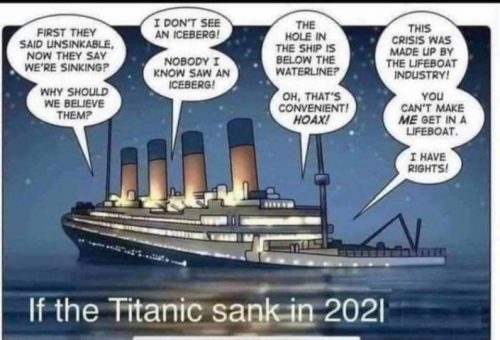

That’s a familiar mantra of the disingenuous internet skeptic, and it could also be the motto of the conservative pundit, from Ben Shapiro to Jesse Watters — you know, the same crowd that says “Facts, not feelings” while simultaneously telling you to trust the authority of unqualified jackasses. I might even have used similar words at times, telling people who are waffling over an idea to go look up the sources. It’s an appealing sentiment that assumes the listener has an open mind, the tools to examine an idea closely, and honestly wants to arrive at the truth.

It’s also a dangerous sentiment.

That’s not how you teach or learn. Smart people — the experts, you know — spent years of careful, disciplined study to build up a body of ideas that are supported by evidence and experiments. They distill their work down into short, intellectually demanding papers that yes, you can criticize, but only if you put as much work into it as the investigators did. It takes hard work to be an expert or authority. Yet somehow we also try to believe that someone should be able to reach a conclusion because we heard a short summary on the television by a talking airhead. “Evaluate” does not mean feed a casual statement into the grinding mass of prior opinions whirring away in your head so you can process the words into justifications for your biases, that is, “form an opinion”.

It takes years of study to become an epidemiologist (or climatologist, or biologist, or whatever complex field of study finds itself in the forefront of the latest crisis), and yet we’re supposed to believe everyone can resolve the conflicting chaos of superficialities they get from their TV into a deep and serious understanding of an issue? People don’t work that way.

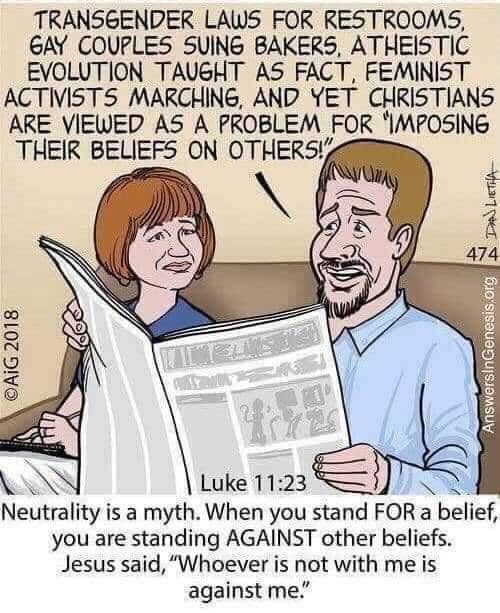

If I’m teaching biology, I don’t tell students to go out and find random sources on their own, and then formulate an opinion on the science. For one thing, I teach them how to evaluate sources first; then I give them a few authoritative sources to prime the pump; then I might ask them specific, narrow questions to address, that require some study to understand and discuss. Then I ground them to reality with tests and term papers, where, for instance, coming to me with a quote from Answers in Genesis to defend the idea that the Earth is 6000 years old gets them a failing grade.

Where’s the exam testing their “opinions” on vaccines? Right now it seems to involve putting them in a hospital with a tube down their throat, which is far harsher than any failing exam I’ve ever graded.