Before fringe groups and weird haters hide behind the label of “science,” they really ought to more aware of what many scientists are actually saying, because they’re far more “woke” than you know. For instance, there is a strong movement within ecology and evolutionary biology to consciously revisit the history and assumptions of the discipline, with the EEB Language Project working to make the terminology more inclusive and recognize the biases in our history. This is a good thing, although some of the more senior members of the field will no doubt squawk about it. Too bad.

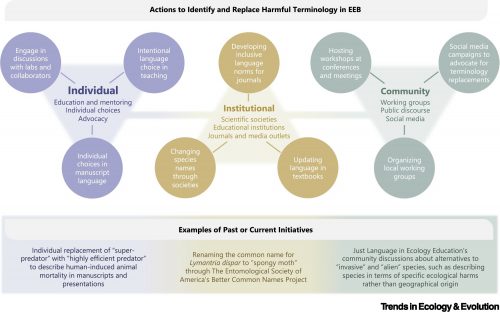

The group has just published a paper, “Championing inclusive terminology in ecology and evolution” that I’m filing away to use in the ecological developmental biology course I’ll be teaching in spring of 2024.

In recent years, events such as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and waves of anti-Black violence have highlighted the need for leaders in EEB to adopt inclusive and equitable practices in research, collaboration, teaching, and mentoring. As we plan for a more inclusive future, we must also grapple with the exclusionary history of EEB. Much of Western science is rooted in colonialism, white supremacy, and patriarchy, and these power structures continue to permeate our scientific culture. Here, we discuss one crucial way to address this history and make EEB more inclusive for marginalized communities: our choice of scientific terminology.

We provide background on how terminology influences inclusion in EEB, describe existing community-based initiatives and our new grassroots effort to champion inclusive language in EEB, and offer guiding questions and considerations for readers committed to using inclusive scientific terminology. This effort is particularly important for redressing the ongoing marginalization of many groups in EEB, including Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) communities; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and/or questioning, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA+) communities; and disabled communities; among others. This work is motivated by the collective experiences, perspectives, and knowledges of our author group. Mitigating the institutional problems in EEB will take significant effort and resources, and examining the role of language in these problems must go beyond attention to scientific terms. It must also include consideration of how language is used among scientists more broadly, and how English is often treated as the dominant language for scientific work. Nevertheless, we propose that inclusion can be fostered by a collective commitment to be more conscientious and intentional about the scientific terminology we use when teaching, mentoring, collaborating, and conducting research.

This affects me, believe it or not. Just last week I was asked whether the spiders I study are an “invasive species.” I was brought up short — I’ve never thought of them that way, even though they are of Eurasian origin. “Invasive” carries an aggressive, dangerous, bad meaning to it, and on the fly all I could say is that they’re no more invasive than human beings, which is kind of damning if you think about it, and that as a synanthropic species house spiders just follow along and occupy the habitat we provide for them. I had found myself made uncomfortable by the implications of the accepted language we use to describe them! This is something other people have been aware of long before I was.

One way that terminology can negatively impact EEB is by creating environments in which students and researchers experience microaggressions, which are incidents that can adversely affect individuals from marginalized groups by perpetuating stereotypes and discriminatory attitudes. For example, one of our authors trained in the USA recalls ‘how tired I was as an undergrad hearing how invasive species from other countries decimate pristine US ecosystems. It reminds me of when people tell me or other people of color to “go back to where we came from”. Why would I want to be in a field that exoticizes immigrants or reinforces narratives that immigrants are a plague?’ Similarly, herpetologist Dr Earyn McGee describes how removing terminology that references historical racial violence against Black people can help create disciplinary environments that feel less exclusionary.

Now I’m wondering what other terminology I take for granted has disturbing implications. I welcome the opportunity to get educated.

By the way, “synanthropic” is a really good word — it just means that they are undomesticated animals that live together with us humans. People live in the company of a small collection of wild, naturally associated animals, like pigeons and raccoons and mice and innumerable small arthropods that find our homes and barns and garbage dumps totally copacetic. I like the fact that it generally lacks any pejorative sense, and prefer to think of it as a statement that there are animals that really like us and prefer our company.