The other day, I got in my car and discovered a few fine strands of silk between the steering wheel and the dashboard. Just a few; some spider had been making a few exploratory leaps inside the car, leaving traces behind, and then probably left because there isn’t much spider food in there. It made me just a little bit happy, though. It’s good to see the little ones out and about.

I can only dream of someday owning a Cobweb Palace.

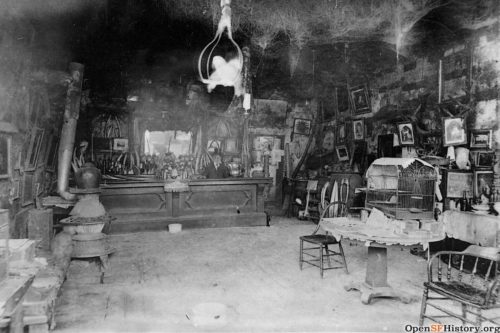

That’s the interior of a San Francisco saloon that existed between 1856 and 1893, established by a wise gentleman and kindred spirit named Abe Warner.

Cobweb Palace was unlike any other saloon in that it had dense spider webs fixed on the bar’s ceiling. More threads draped over the shelves that stored the liquor bottles. The spiders cast a veil over nude portraits on the walls, and some of the webs reportedly grew 6 feet wide at times. But Warner refused to destroy them.

“The spiders just took advantage of me and my good nature,” Warner told the San Francisco Chronicle. “When I first opened up here, I didn’t have time to bother with ‘em and they grew on me. It’s a great neighborhood for spiders, anyway, and the news got around among ‘em that I was easy and they founded an orphan asylum and put all the orphans to work spinning webs.”

All good things must come to an end, though, and the enchanted saloon eventually failed after a prosperous 40 year run.

Cobweb Palace would continue showcasing its curios, wild animals, and web-covered ceiling for nearly four decades, until the crowd outgrew their taste for the peculiar fortress Warner created. The saloon began to lose its luster in the 1870s, when the area became mostly industrial. Years later, the Sausalito ferries moved away from Meiggs’ Wharf, causing a bigger blow to Warner’s business.

Customers stopped coming to Cobweb Palace and Warner couldn’t make enough cash to pay the rent. The property owner had no choice but to evict Warner by 1893 to tear down the saloon and make way for new housing.

The end of Abe Warner was especially poignant. Is this me in a few years time? If it is, it’s not that terrible a way to go.

Warner is remembered in historic articles as a man whose only friends were the spiders, and in a way, they were. Warner’s best days were among the spiders that coexisted inside his bar as they kept him company long after the crowd abandoned him. Some webs had been undisturbed since the saloon’s inception until the auctioneers finally cleared them out.

Warner refused his daughter’s call to return to New York after the failure of Cobweb Palace. It would be too painful of a move after the decades spent in San Francisco. Even when local relatives wanted to take him in, Warner declined their offer, preferring his own solitude. Then, three years after the saloon’s permanent closure, Warner passed away in 1896 without a dime to his name. He was 82 years old and died alone, save for the spiders that watched over him until the very end.

What’s especially sad about that is that I haven’t accomplished anything as glorious as the Cobweb Palace. I’m going to have to get to work fast in my remaining years.

Also, anyone else read his story and think he sounds like a great character for an urban fantasy novel?