The Tully Monster has been an enigma for half a century. Now it’s been reconstructed on the basis of analysis of 1200 specimens.

That thing is weird. It’s been extinct since the Carboniferous, though, so we’re not going to be catching any nowadays, unfortunately. Note the eyes on stalks; the tubby body; the long ‘snout’ terminating in a toothy jawed mouth. People have been grappling with its taxonomic identity for decades, and it’s been labeled as various kinds of worms, or a mollusc, or an odd relic of some Cambrian phylum.

The latest comparisons, though, have convincingly identified one common trace in the fossil as the remnant of a notochord — that makes it a chordate, and everything else begins to fall into place. It’s got a 3 lobed chordate brain, and gill openings, and rays of cartilage internally, and segmental myomeres. Not only is it a chordate, it seems to be a relative of hagfish and lampreys…their weird funny-looking cousin. And when you’re funny-looking compared to a hagfish, you’re really out there.

Now though, I want to know what they were doing while they were swimming about here in the Midwest 300 million years ago. What were they eating with that strange proboscis?

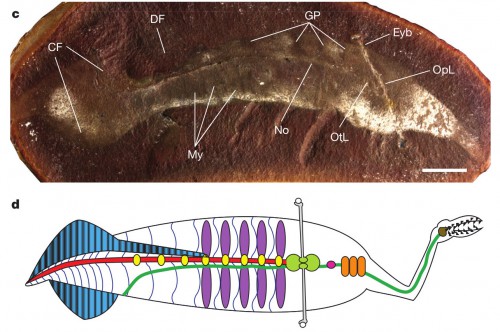

Tullimonstrum, FMNH PE 40113,

oblique lateral view (also Extended Data Fig. 2a): eyebar, Eyb; myomeres,

My; gill pouches, GP; caudal fin, CF; notochord, No; otic lobe, OtL and

optic lobe, OpL of brain; and dorsal fin, DF. d, Line drawing: black, teeth;

brown, lingual organ; light grey, eyebar; dark green, gut and oesophagus;

red, notochord; light green, brain; orange, tectal cartilages; pink, naris;

purple, gill pouches; yellow, arcualia; dark blue, myosepta; blue with black

stripes, fins with fin rays. Scale bar, 10 mm.

VE McCoy, EE Saupe, JC Lamsdell, LG Tarhan, S McMahon, S Lidgard, PMayer, CD Whalen, C Soriano, L Finney, S Vogt, EG Clark, RP Anderson, H Petermann, ER Locatelli, DEG Briggs (2016) The ‘Tully monster’ is a vertebrate. Nature doi:10.1038/nature16992.

Not Telly Monster.

http://muppet.wikia.com/wiki/Telly_Monster

I’m thinking it was a fish-catcher. Those teeth are ideal for holding live fish, and the eyes on stalks gave it stereo vision for steering that long snout. The body looks streamlined, so it may have travelled at speed, with the eyes tucked in, or just snuck up quietly and struck.

It looks completely fantasmical to us, and it probably confused the heck out of fish, too. That snout could grab while the body was off at what seemed a safe distance.

If the thing had a gullet that wouldn’t collapse (like our trachea), it might have pumped water out through those big gill holes, and the mouth would pull in water, giving a suction drive to the snout (requiring only steering, not thrusting power in the snout), and the suction would draw in the fish a bit.

Keep in mind it’s also small — look at the scale bar on the fossil photo.

Looks like a babel fish to me!

Very cool after all these years that Tullimonstrum turns out to be a chordate. That proboscis looks like it should be eversible, but today’s lampreys have a “snout” of sorts, with rasping teeth that they use to latch on to passing fish.

I understand many of the fossils preserve the “proboscis” bent in same three places, leading some to interpret it as jointed.

I believe I first heard of the Tully Monster reading S.J. Gould in the late ’70s. So much fun when old questions get answers.

And there’s always more to look forward to.

That’s totally a hoax. What a ridiculous body plan.

Perhaps the end of the mouth was illuminated as a bait? Baited by light, the teeth hold, similar, but different from the anglerfish?

It never ceases to amaze me what can be built with a mere four letters!

I don’t see the toothed end of the proboscis in the fossil at all. It reminds me far more of a paddlefish than lampreys or hagfish. I imagine it using that proboscis to probe the mud and burrows for various invertebrates. The stalked eyes are odd, but they would be very useful if your mouth was always stirring up sediment.

When I first saw, decades ago, the drawings of Hallucinogenia, I thought it was just too out there, until it was shown that the representation was wrong and Hallucinogenia was close to Onychophora.

While I do respect the work of people vastly more competent than me, and the reconstruction is based on a richer pool of samples than Hallucinogenia, the same uncanny feeling remains about Tullimonstrum.

Then again, it seems like a similar elongated mouth was found in Opabinia (convergent evolution?) so maybe it made sense at the time? I really wonder what this was eating too.

PZ

I see the scale bar, I don’t see any numbers.

mm?

fathoms?

ri?

@chigau (#10): Bottom of the caption, “Scale bar, 10 mm.”

The Tully Monster looks to me like somebody’s still playing “Spore.”

Darren Naish(of Tet. Zoo) to the Red phone please, assistance required.

Tethys @ 8:

This is far from the only specimen studied, the team looked at over 1200 specimens and the proboscis with teeth is quite clearly seen in them. Fig 3 in the paper shows it off particularly well. Pretty incredible stuff.

Here is the paper itself, if anyone wants to read more about it.

http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/vaop/ncurrent/pdf/nature16992.pdf

A long snout, putting the mouth a whopping 4cm or more from the eyes (and more from the gills), looks very handy for rooting around in sediment (while you watch out for predators from all directions).

Very cool, no matter what kind of tiny beasts it turns out to have eaten.

The mildly deranged penguin says it is an Atlantian Cheesesniper. A baby, perhaps only a week old, but hard to tell if it’s male-male, male-female, or female-female.

Some of the best Atlantis cheese were aquatic or semi-aquatic. The semi-aquatic ones lived in the coastal swamps, frolicking in the sun, and were generally vegetarian. They were quite easy to approach, but could dart away quite quickly and were very very slippery, so hard to catch. The usual method of catching them was to herd them onto the land, were they were slow and unable to climb over rocks. You could then just basically pick them up, albeit because they were so slippery, they would frequently squirt out of your hands. Dried-off and diced, they made an excellent ingredient in salads, and especially in the toppings / sauces for pizzas, casseroles, and so on. They tended to spoil quite quickly and so had to be served fresh.

The coastal aquatic cheeses were related, but had developed a hard crust and supplemented their diet with seabirds. They could chew through nets, so were generally caught wild by spear-fishing, or farmed in isolated lagoons. The wild ones had a very strong taste and needed to be aged.

But it is the deep-sea cheeses which are of interest here. These could be monsters, biting ships in half and, like their coastal cousins, feasting on “seabirds”, albeit in their case, usually Pterodactyls. They were jet-propelled, albeit unlike modern squid, not with jets of water, but of air from a massive internal reservoir. Waste (remains of ships, Pterodactyls, any islands they collided with, and so on) were also expelled in the jets. You could hear and smell them coming. To be caught in a jet was usually a once-in-a-lifetime experience, because you’d usually be dead.

But that reservoir was also their Achilles Heel: If it emptied, they were helpless, a great floating cheese not unlike an algae mat. As long as they stayed floating and the reservoir wasn’t punctured, they could usually reinflate.

Enter the Atlantian Cheesesniper. It is not, despite the common myth, an artificial creature escaped from some mad doctor’s vats. The mildly deranged penguin does not know its evolutionary history, but will be happy to make one up.

As its name suggests, it ate deep sea cheeses. Specifically, the biggest, baddest, smellyist, albeit not quite the fastest, the dreaded Lump’o’Grey. Which was basically a very strong blued cheese. The Cheesesniper’s hunting strategy was quite simple. It waited to be ate.

The “eyestalks” are actually nosestalks, each contains a highly directional odour detector, quite sensitive to gases in the Lump’o’Grey jets. The stalks themselves acted like ears, although it is a matter of debate how directional they were. Most cheese hunters think they worked out the general direction of an incoming Lump’o’Grey by comparing the vibrations detected by the stalks, and then homed-in on the target using the directional noses.

The Cheesesniper would very carefully position itself, facing backwards, to the targeted Lump’o’Grey. The cheese would then come zooming in and swallow the Cheesesniper whole and tail-first. As the Cheesesniper disappeared into the cheese, that toothed snout would take a bite out of the Lump’o’Grey cheese.

Two things could happen. One, if it failed to hold on, it could just have a nice meal of a tasty cheese and then be shot out with the jet to hunt again.

Or, two, if it got lucky and chomped on the correct area, it would puncture the air reservoir. If it managed to hold on inside the cheese whilst the cheese uncontrollably zoomed around, deflating, then once the Lump’o’Grey was out’o’air, the Cheesesniper, still inside, would have a grand feast.

Baby Cheesesnipers, like the one pictured, could not take down a fully-grown Lump’o’Grey. So they grew to be quite large, albeit not the “half a ship” size of the myth. Lump’o’Greys could still swallow a fully-grown Cheesesniper, a mistake they generally made only once, as that often resulted in deflation.

Sadly, Cheesesnipers disappeared sometime between the fifteenth and eighteenth sinkings of Atlantis. The mildly deranged penguin insists she didn’t cause at least one of those sinkings.

I’ve seen a weird-looking water creature with eyestalks called “Tully” in a Morrowind mod once and had no idea wtf it was supposed to be. Now, years later, I finally know. Thank you!

If it was truly a cousin of either hagfish and lamprey, then that small, spindly, delicate-looking mouth-stalk and weak swimming fin would be perfect for slow scavenging, or – and hear me out – maybe overspecialized parasitism? Early amphibians and bony fish, some with gill slits or olm-like exposed gill fronds would prove for easy, bloody nutrition for such a somewhat small animal of only around 11cm.

The 3D illustration looks mostly like a fishing lure (a plug or a swimbait).

ALL TOGETHER NOW:

We all live in a yellow submarine, a yellow submarine, a yellow submarine.

We all live in a yellow . . .

Shewed thus to a guy I work with and he had the same first impression.

And I agree with Ice Swimmer — definitely looks like a fishing lure.

Nice elbow throat.

That’s totally a hoax. What a ridiculous body plan.

A body plan intelligently designed to resemble a hoax!

That’s adorable. I hope it really was bright yellow, too.

I’d beg to differ, as most survivors report being dead AFTER they were (initially) hurled through the air by the jet.

Ptolomy, in his lesser-known-but-no-less-important Jetrabiblos (Jετράβιβλος or “Jet Books”), wrote extensively upon the nature and effects of the Jet blasts on human, animal (mostly cattle) and large barges. He interviewed and examined the remains of victims of Cheesesnipers and came to scientifically-sound conclusions, a remarkable feat at the time.

The proboscis looks well adapted to getting prey out of crevices and holes, or worms out of their burrows. That would also explain the eye stalks — if you’re face down in the muck, you need peripheral, 360 vision to detect incoming predators.

Looks like something in which a Vorlon would tool around the galaxy.

Bloody hell, blf, you have too much time on your hands!

w00dview

Cool, thanks for the link. Teeth are kind of my specialty, so I really wanted to look at the oral structure. I just couldn’t tell if my eyes were deceiving me, or it really wasn’t visible in that picture, because 3 am and way past bedtime. I still disagree with stem hagfish, but those photos are indeed amazing.

No problem, Tethys. I don’t blame you being a bit skeptical at first a it is quite a fantastical looking creature so happy to provide some more context to its discovery. Easily one of the most extraordinary fossil discoveries in quite some time imo.

Thanks for the link. I’m interested in reading it, but not $32 worth of interested. Oh well.