Quirks of nature happen all the time. When we pay attention to an inconsistency, our motivation is usually to delegitimize a person, idea, or movement. Hopefully, these quirks are not fatal. Inconsistencies may not matter if there is a net benefit or if the purpose is achieved. The above is no more inconsistent than the idea that we want to minimize murder through capital punishment. What about a doctor who is treating us for cancer but has never had cancer, the drug addict preaching to us not to use drugs, or conservatives hating their government but loving their country? Although it feels like hypocrisy or inconsistency, which we are good at detecting, none of this matters for the purpose of treating a patient, giving good advice, or following the dictums of an ideology.

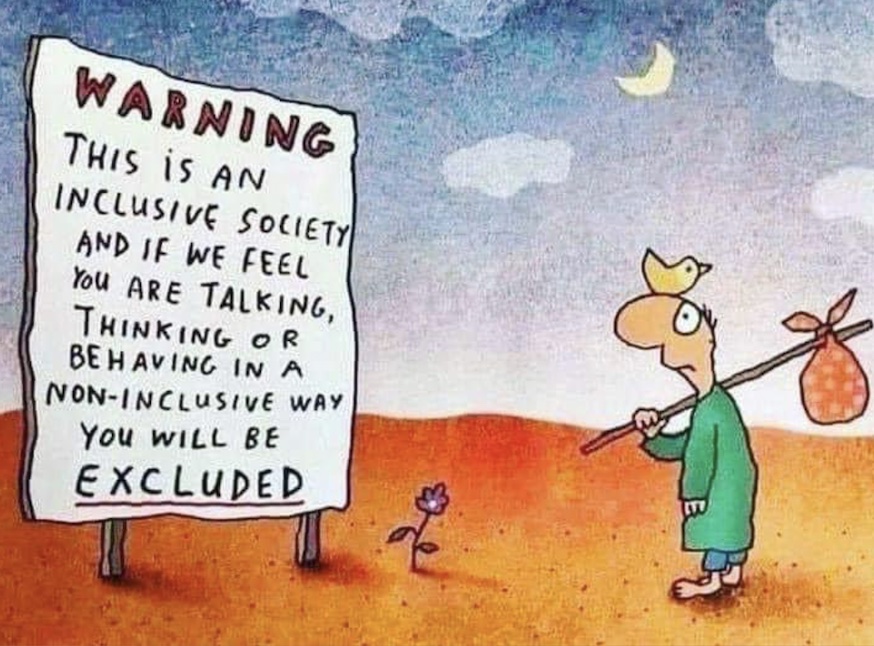

The cartoon says that in liberals’ efforts to increase the inclusion of marginalized others, we end up excluding those who do not want to participate. We can view this as irony or as pragmatism. It is a punitive mechanism to improve the status of a group of people by creating acceptable speech and behavior. We may lose some people along the way, but as was the case for women and gays, the net effect is that these people rise in political and cultural status (i). The two complaints of political correctness are, one, it robs us of our freedom of expression and, two, it privileges one group at the expense of other groups. There is confusion regarding these two points, which deserve a separate post. Especially since the left is characterized as follows in the event of Salman Rushdie’s death.

The first group (liberals) believes they are motivated by inclusion and tolerance—that it’s possible to create something even better than liberalism, a utopian society where no one is ever offended. But it is the indulgence and cowardice of the words are violence crowd (liberals) that has empowered the fundamentalists and allowed us to reach this moment, when a fanatic rushes the stage of a literary conference with a knife and plunges it into one of the bravest writers alive.

There are five cases to look at that demonstrate inconsistencies. The first case is compromising morality in order to produce a net positive effect. Typically these compromises are not deleterious. If we want to increase the status of the LGBTQ+ community, then there must be consequences for behaving poorly towards them. Even though we want to minimize exclusion, the exclusion of detractors is used as a tool because it is effective. The second case is when two things are inextricably tied together. In abortion, if we do one thing (woman), then it affects another thing (baby), and vice versa. The third case is hypocrisy. A drug addict telling us to not use drugs is good advice. This only becomes hypocrisy if the addict were to cast judgment on us. The fourth case involves empathy. A doctor would understand how to treat cancer regardless if he had it, but he may not be sympathetic towards us. A fifth reason why inconsistencies appear is that worldviews have an underlying logic that dictates how political issues are handled.

Inconsistencies of Worldviews

As another example, libertarians condemn altruism as immoral but say by the way helping others is alright. This is more than an inconsistency since it negates the purpose of their goals, which are to maximize self-interest and condemn altruism. It only shows their desperation and failure in reconciling real-life morality with their dogmatism. Most people believe that extreme selfishness is immoral and altruism is moral. To make their philosophy work, they would have to say that altruism as sacrificing ourselves to our own detriment or being forced to sacrifice is immoral. Despite this, coercion may help the common good. This shows that the real purpose of their condemning altruism is to prevent providing for the common good. But wait another inconsistency shows its face.

How can liberals believe that providing for the common good is a moral act if we have to force many to do so? Libertarians rightfully say that taking from someone’s income to give to another person through coercion is theft and immoral. If it is involuntary, then we would have to agree. But there is often a net benefit because it serves the purpose of lifting many out of poverty and reducing the corrosive effects of status inequality. So we compromise morality in order to serve the greater good. It is called deep pragmatism. Besides being the moral thing to do, which is to help those in need, there are good selfish reasons to subscribe to serving the common good. The second post on “Libertarians Don’t Get a Lot” will explain in detail how the common good is in our best interest.

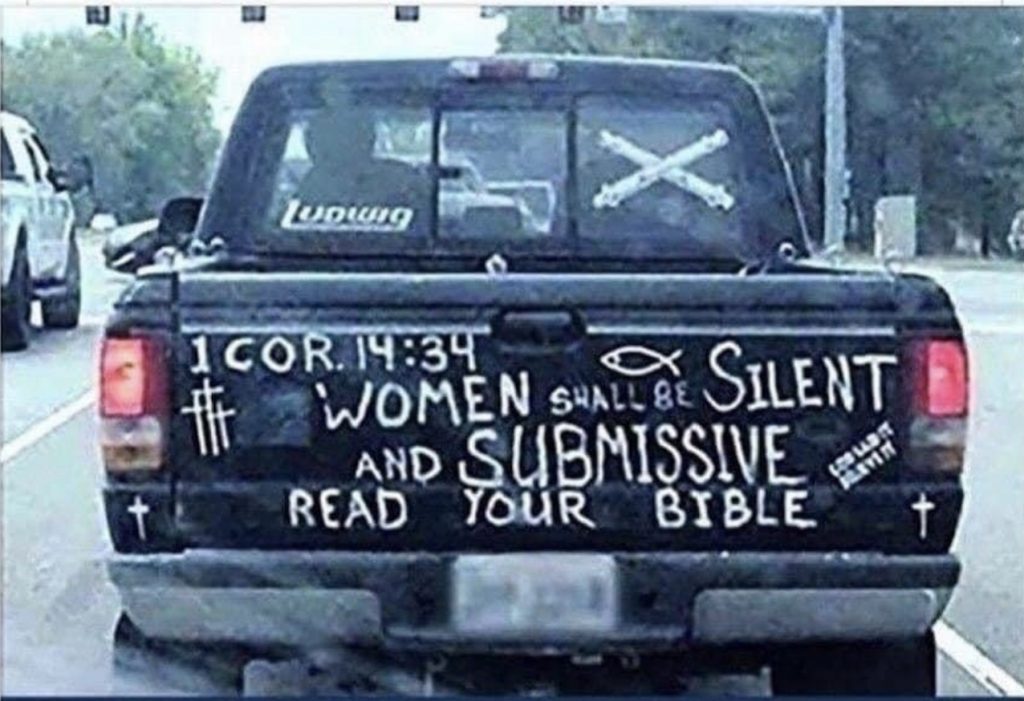

How about conservatives who are pro-life but endorse the death penalty? There is a perfectly good reason why they are this way and it has to do with the logic of their worldview. It is just a consequence of the way things work out. The logic follows from their morality of rewards and punishment. They punish those who murder with consequences that fit the crime. What about the origin behind forcing women to have an unwanted pregnancy? There is a hierarchy for their worldview: men above women, white men above minorities, …, and straight above gay. The female is supposed to raise the children and not seek out a professional career. She is in violation of their hierarchy, which brings resentment. Since she ranks lower than the male, she must be submissive.

This only explains how they can force females to give birth but not why they are pro-life. The Bible is silent on abortion. Abortion evades self-discipline and personal responsibility, which are staples of their worldview. A teenage girl, for example, should not be indulging in sex and should be practicing self-restraint. She deserves to be punished not coddled; she deserves to pay the consequences of her actions. But why then are conservatives against funding programs to reduce infant mortality through pre and postnatal care if they want to save the baby? Because it has nothing to do with saving the baby and everything to do with personal accountability. Furthermore, to a conservative, government handouts prevent people from becoming self-reliant and self-disciplined.

Why do liberals side with the mother during an abortion and not the unborn child? Why do they choose to nurture the woman with empathy and support but not the baby? Liberals tend to care a lot about the harm done to the marginalized, the environment, and animals and endorse protectionism as a result. But why does the unborn child not deserve any protection? This is an inconsistency in the application of values. They claim it has to do with liberty which is the freedom to do as we wish as long as we do not interfere with the freedom of others. What about the baby’s freedom from being killed? Liberals overcome this by claiming supremacy of the woman’s right to her own body. But whose rights win, the babies or the women? They are tied together, so it is an either-or result.

Why do conservatives love their country but hate their government? If we view the government as a metaphor for the father of a family (the populace), then conservatives do not want their father to interfere with their own family. The father does not know what is best for our own family. He is a meddler and interferes on issues (local state issues) in which he is no expert. His meddling brings resentment and interferes with our liberty. The government’s forefathers represent the country and are to be mystically admired.

Notes:

i) For millions of years, we lived within homogeneous tribes of no more than one hundred people with the same beliefs, values, race, and ethnicity. We are now forced to tolerate people from all walks of life. No one is asking anyone to wholeheartedly embrace LGBTQ+, minorities, and women but at the very least be respectful and tolerable. We cannot force acceptance, but we can create social norms to create tolerance. Hopefully with time tolerance leads to acceptance. The best way to breed acceptance with people that are different than us is to look for what we have in common. This leads to empathy instead of hate, contempt, and fear. For a lot of people, however, it appears that hate and fear are the default positions. This means political correctness has an integral role.