The Probability Broach, chapter 9

Having fended off his nighttime attacker, and with extra security in place, Win resumes mending from his injuries using the North American Confederacy’s advanced medical tech.

While he’s healing, he does some research on Ed’s computer, trying to understand why this world turned out so differently from his own:

Who can explain their own times and the past that created them? I don’t remember enough from high school and a junior college curriculum in police science. What little I can parrot is just a hodgepodge of other people’s opinions.

Hell, they revise it every year. I never did figure out what caused World War I, and with each decade World War II seems more FDR’s doing than Japan’s. If I didn’t understand my own world, how could I understand this one?

Ed and Clarissa didn’t have quite the same problem. For them, there’d never been a World War II; no Roosevelt I could discover had ever scored higher than dogcatcher.

This was one of those lines that made me raise my eyebrows. Blaming World War II on Roosevelt?

Arguably, you could blame World War II on the victors of World War I, including Woodrow Wilson, who imposed punitive terms on Germany that created a sense of national humiliation and fed a desire for revenge. But why FDR? How could he possibly be responsible when the U.S. didn’t join WWII until it had already been raging around the world for two years?

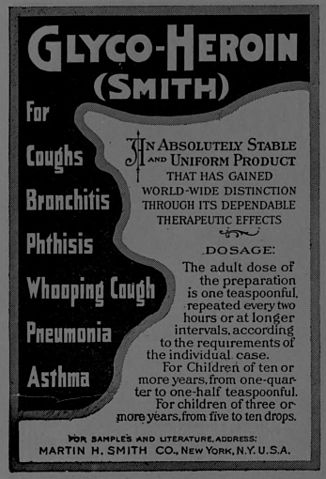

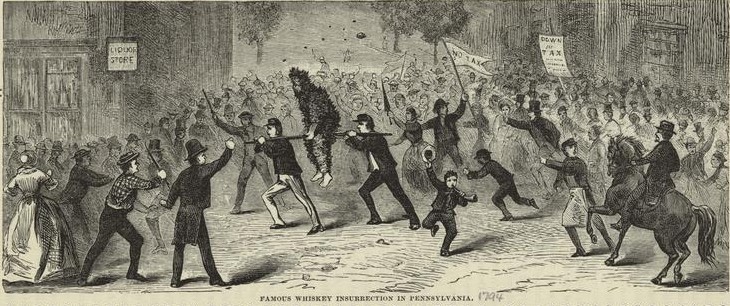

It turns out that this is a common opinion among libertarians. The Libertarian Institute published an essay, “Roosevelt’s Infamy“, which asserts that FDR wanted the U.S. to enter World War II and schemed to provoke Japan so as to create a casus belli:

FDR began his machinations by doing everything he could to provoke the Germans into attacking U.S. vessels in the Atlantic. In that way, he could exclaim, “We’ve been attacked! Now, give me my declaration of war!” But the Nazi regime knew what FDR was up to and refused to take the bait.

…That was when Roosevelt turned to the Pacific, in the hope that a Japanese attack on the United States would give him a “back door” to the war against Germany.

That’s what FDR’s oil embargo against Japan was all about. Japan had invaded China and was occupying the country. Its war machine necessarily depended on a continuous supply of oil. The purpose of FDR’s embargo was to prevent Japan from acquiring that badly needed oil.

FDR’s oil embargo was remarkably successful. It maneuvered Japan into a position of having to make a choice: Either invade the Dutch East Indies to secure its oil supplies or meekly withdraw its military forces from China.

…Not surprisingly, Japan decided to invade the Dutch East Indies rather than withdraw from China. But Japan knew that the invasion stood the risk of the U.S. Navy interfering with its operations in the Dutch East Indies. That was what the attack on Pearl Harbor was for—to knock out the U.S. Pacific fleet so that Japan would have a free hand in securing those oil supplies in the Dutch East Indies.

The Mises Institute agrees, in an article titled “How U.S. Economic Warfare Provoked Japan’s Attack on Pearl Harbor“:

When Germany began to rearm and to seek Lebensraum aggressively in the late 1930s, the Roosevelt administration cooperated closely with the British and the French in measures to oppose German expansion. After World War II commenced in 1939, this U.S. assistance grew ever greater and included such measures as the so-called destroyer deal and the deceptively named Lend-Lease program. In anticipation of U.S. entry into the war, British and U.S. military staffs secretly formulated plans for joint operations. U.S. forces sought to create a war-justifying incident by cooperating with the British navy in attacks on German U-boats in the northern Atlantic, but Hitler refused to take the bait, thus denying Roosevelt the pretext he craved for making the United States a full-fledged, declared belligerent—a belligerence that the great majority of Americans opposed.

…The Roosevelt administration, while curtly dismissing Japanese diplomatic overtures to harmonize relations, accordingly imposed a series of increasingly stringent economic sanctions on Japan… Roosevelt and his subordinates knew they were putting Japan in an untenable position and that the Japanese government might well try to escape the stranglehold by going to war.

This is an astonishing position for libertarians to take.

Libertarianism is supposed to be founded on the non-aggression principle, which says you can’t use violence against someone unless they start the fight. Then you can strike back to defend yourself.

There’s a patently obvious fact that’s missing from these analyses: Even if FDR wanted to involve the U.S. in WWII, he didn’t start the war. The Axis nations did that, by coming up with imperialist, supremacist ideologies that justified their desire to control the world, then followed through by invading neighboring states – Poland in Germany’s case, China in Japan’s – and treating the conquered populaces brutally.

Why doesn’t that count as use of force? Why didn’t it justify U.S. involvement, to assist in defense of the countries that were under attack?

In essence, these libertarians are arguing that Imperial Japan was entitled to whatever resources it needed to expand its empire, and that Roosevelt refusing to sell those resources to them was an act of violence that justified the attack on Pearl Harbor. It’s like saying, “I have the absolute right to trade with you, and if you won’t sell me what I want to buy, I can shoot you.”

This should be anathema to a principled libertarian. Somehow, it doesn’t bother them. These groups claim to be anti-aggression, but it seems that as long as someone other than the U.S. starts the war, it’s fine by them.

I was going to draw an equivalence to today’s conservatives pretending not to know who started the Russia-Ukraine war, but they make this comparison themselves:

As an aside, it’s worth mentioning that more recently, U.S. officials, operating through NATO, maneuvered Russia into having to make a similar choice: Either accept Ukraine’s membership in NATO, which would enable the Pentagon to station its nuclear missiles and troops along Russia’s border, or invade Ukraine to prevent that from happening.

Again, this is a bizarre stance for a professed libertarian to take. They’re saying that Ukraine wanting to join NATO as defense against a Russian invasion was an aggressive act that justified that very invasion. In black-is-white libertarian-land, if someone takes steps to defend themselves against you, that justifies you attacking them.

(Ironically, there are factions on the socialist left who make the same error as these right-wingers. They both assume that only the U.S. has agency, and that our choices determine how the rest of the world reacts, so anything that happens must be our fault.)

To be clear, I don’t think the U.S. is responsible for policing the world, or that we have a moral obligation to overthrow every oppressive regime. We don’t have the power to do that, and it often ends badly when we try, as our prolonged failure in Afghanistan made painfully clear.

However, a reasonable middle ground is that we can, at least, not support regimes that wage war on others or oppress their own people. We can peacefully express our disapproval and limit their power through trade embargos and sanctions. That position seems like it should be congenial to libertarian thinking. However, actual libertarians don’t agree.

Again, why Roosevelt in particular? What did he do to earn L. Neil Smith’s enmity?

The libertarian hatred of FDR is also on display in Ayn Rand’s writings, and that gives a better view of their reasoning. Libertarians will tell you they loathe FDR because his New Deal was a massive government imposition on the free market. That’s closer, but still not the truth.

The true reason for their hatred, I think, isn’t because the New Deal was a government imposition on the economy, but because it was an effective one. Most of the New Deal programs are still in existence today, and they’re so popular that even conservatives are reluctant to touch them.

In other words, they hate FDR because he showed that government can work well, which goes against their anti-state ideology. They want to tear down his record by proving that everything he did was driven by sinister motives. But in order to do that, they’re forced into siding with the most infamously evil regimes in history.

New reviews of The Probability Broach will go up every Friday on my Patreon page. Sign up to see new posts early and other bonus stuff!

Other posts in this series: