This is a repost of an article I wrote in 2008, over ten years ago! This is the one that explains where my avatar comes from.

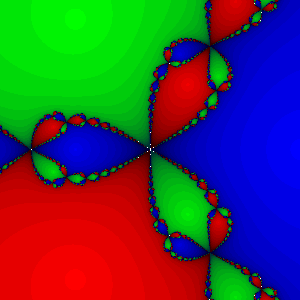

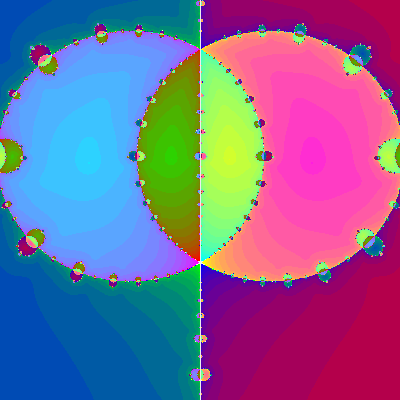

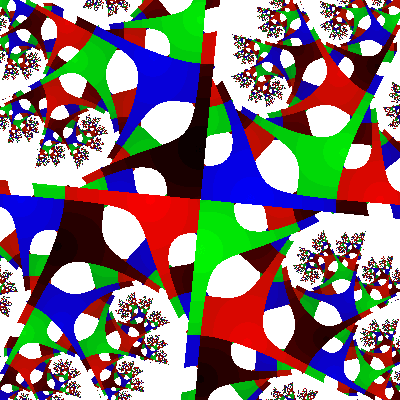

Today, I will explain how I created this:

This is a fractal. A fractal is a pattern that contains smaller versions of itself. But it’s not just any fractal. It’s a fractal I created from something called Newton’s method.

Newton’s Method

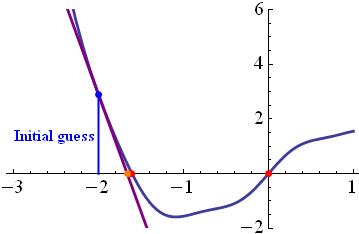

Let’s say we have a mathematical function called f(x). I chose one specifically for this demonstration. Here is a graph:

A very common math problem is to find the “roots” of f(x). That means you’re trying to find what numbers “x” can you use to make f(x) equal to zero. In a graph, that means that it touches the horizontal axis. In the picture above, the roots are all shown with red dots. You can see that one root is zero, and the others are near 2 and -2.

It’s easy for me to make an instant estimate of the roots, but that’s because I had a computer graph it for me. What if I were, say, Isaac Newton, and I had no computers? What if I wanted a really accurate estimate of the roots? I would invent a new mathematical method and name it after myself, of course. And that’s what Newton did.

Newton’s method relies on the fact that most functions are more or less straight. The graph of f(x) sure doesn’t look straight–it curves all over the place. But if we zoomed on just one part of the graph, it would be almost straight. An almost-straight line is almost like a straight line. So it stands to reason that an almost-straight line has almost the same root as a straight line. In the above graph, I started by “guessing” the location of the root at -2. Using this guess, I drew a “tangent line” to f(x). This tangent line is a straight line that just barely touches f(x) at the blue point. Finding a tangent line is a standard method from calculus. If we just find the root of the tangent line, we know it must be fairly close to the root of f(x).

In the above graph, I started by “guessing” the location of the root at -2. Using this guess, I drew a “tangent line” to f(x). This tangent line is a straight line that just barely touches f(x) at the blue point. Finding a tangent line is a standard method from calculus. If we just find the root of the tangent line, we know it must be fairly close to the root of f(x).

Notice that we started with an initial guess of -2, and we got a much better guess. That means we can take any guess and make it into a better guess! There’s no reason to stop there. All we need to do is repeat the process, starting with a better guess each time. You can get a very good estimate of the root of f(x) very quickly.

When you guess badly…

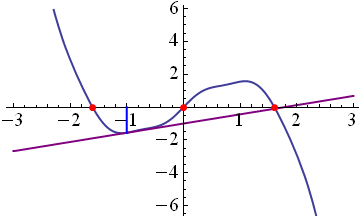

The trouble with Newton’s method is that functions aren’t really straight. They can curve all over the place! Let’s see what happens when I try a different initial guess of -1.

After only one iterations, it looks like we’re getting a very accurate approximation of the root near 2. But wait, didn’t we initially guess -1? Even though our initial guess is between the first two roots, we end up finding the third root. Newton would probably consider this a bad guess, because we didn’t find the root we wanted to. However, we have a different idea in mind.

We want to answer the question: Given any initial guess, which root will we eventually find?

Though the original method was invented in the time of Newton, this is a question that they never could have answered. What if a single guess bounces around for a while, before finding a root? You really need to use a computer to test all the possibilities. So that’s what I did.

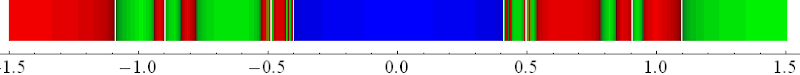

(Click for a bigger picture.) When you guess badly, you get a fractal!

Allow me to explain the meaning of the fractal. Each color corresponds to a different root. The darkness of the color corresponds to the number of iterations required to get the root. Of course, you never quite reach the root exactly. But once it’s within a certain distance, the computer decides that it’s close enough. Some guesses are so bad that they don’t ever find any root (at least as far as my computer has tried). Those guesses are indicated in white.

It’s actually not too surprising that this method would result in fractals. First you have the large regions which correspond to good guesses. Then you have small regions of bad guesses. These “bad guess” regions map to the rest of the number line. And so, the “bad guess” regions will end up looking like smaller versions of the entire fractal.

More complex, More fractal

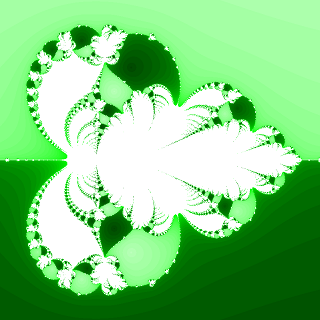

So far, I’ve only explained how to make a 1-dimensional fractal. The one-dimensional fractal maps the number line to different colors. But at the top, I showed you a 2-dimensional fractal. The 2-dimensional fractal maps the complex plane to different colors.

The complex plane is a sort of extension of the number line into two dimensions. It includes the “real” numbers, like -1, pi, and sqrt(2). It also includes “imaginary” numbers, like “i”, the square root of negative one. And then there are complex numbers, which are in the form a+b*i. The number “a” is called the real part, and “b” is called the imaginary part. The real part is represented by the horizontal position on the complex plane, while the imaginary part is represented by the vertical position.

Otherwise, the method is exactly the same. Only now, it’s prettier. And there might be new roots that were previously hidden.

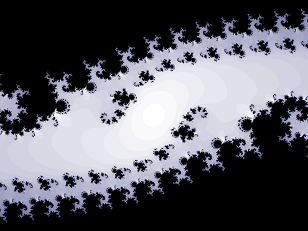

The fractal at the top was generated using the function f(x) = x^3-1

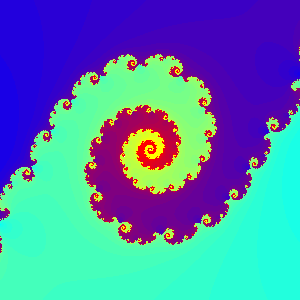

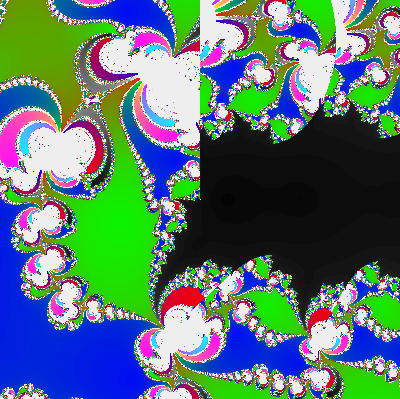

But I have tried much more complicated functions as well. Some of you might recognize this one, because I use it as my avatar in certain internet locales.

This one was generated by the function f(x) = x*cos(x)^i. This function has only one root. The black regions correspond to guesses that never lead to the root.

This was generated by the function f(x) = log(x) + x. I also made a nice desktop-sized version, ’cause it’s so awesome.

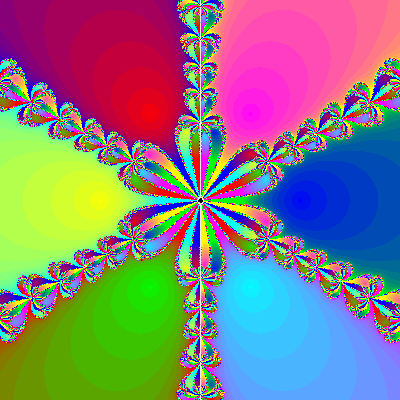

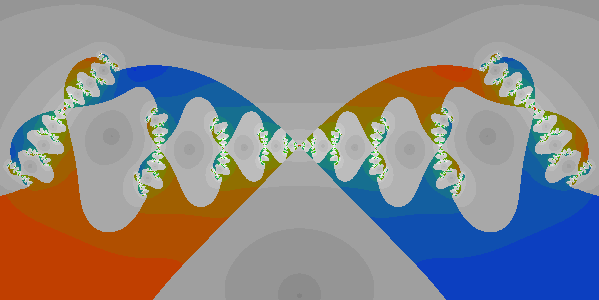

This is the function f(x) = ex – x. This function has an infinite number of roots, only two of which are being shown.

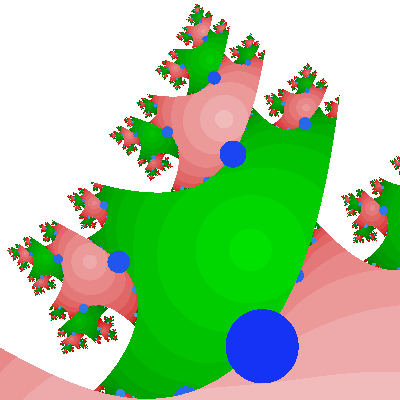

This is f(x) = log(x2). I had posted this on my blog last Christmas. The blue “ornaments” are actually an exploit in my computer program; they wouldn’t normally be there.

These are all generated using a Java program that I made for a high school project. I have found it very fun to experiment with this math-to-art device. I want you all to have a taste of that. So… later, I will be taking requests for mathematical functions!

Bonus fractals for 2020

When I posted this in 2008, I only showed a selection of what I thought were the best fractals, but I have a lot more in my files. So let me throw even more at you.

x^6-1

x^-3 – x^3

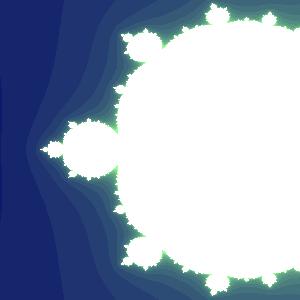

x^.5+x^1.5/4. It looks like the Mandelbrot set but as far as I know it is not.

(x^2)^i * (x^2-1)

arctan(x-i) – arctan(x+i) + ix. You may have noticed that some of these fractals have hard edges in their patterns. That’s because certain functions, like arctan or ln actually have multiple solutions in complex numbers, and if I write the program to pick just one solution it’s no longer a smooth function.

ln(z^4)

e^x + ln(x)

And that’s still just a sample.

Gorgeous. I spent WAY too much time playing with stuff like this in the 80s when computers were Slllllooooowwwww. Then my uni got Sparcstations!

Fun with Fractals! I wonder at times if there are other kinds of math out there that are waiting to be invented/discovered that can explain the things we don’t yet know about the universe, (or don’t know that we don’t know). Math seems to be the answer to everything. Maybe it’s the real “One, true God”.