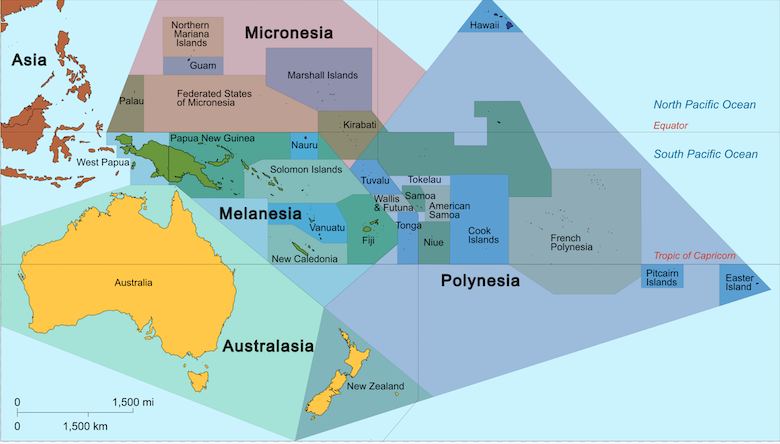

The Pacific Ocean covers almost half the surface of the Earth and despite its name can be the scene of massive storms. The entire region can be split into three regions, Micronesia and Melanesia that are on the western end of the ocean, close to Australasia, and Polynesia that occupies the central region. Polynesia is vast as can be seen by the size of the so-called Polynesian triangle consisting of Hawaii as the northern vertex, Rapa Nui (formerly called Easter Island) as the southeast vertex, and New Zealand as the southwest vertex. Each side of this triangle is about 9,000 miles. The people of Polynesia, despite being so widely dispersed, form a single, identifiable cultural group.

Even though there are many island archipelagoes in the ocean, the total amount of land that makes up the islands that dot the ocean is minuscule although that aspect can be obscured by atlases that label the islands since the lettering that gives the names are much larger than the islands themselves. Take away the labels and there is nothing there unless one greatly magnifies the scale. Although the Polynesian triangle covers 10 million square miles, the area of actual land is approximately 300,000 square miles. If we leave out New Zealand and the Hawaiian archipelago, we are left with just 15,000 square miles for all the other islands, just 0.15% of the total area of the triangle. Within this huge triangle are familiar places like Samoa and Tonga plus various archipelagoes such the Cook Islands, Society Islands (which contains Bora Bora and Tahiti), the Marquesas and the Tuamotu archipelagoes.

These islands are all just tiny dots in the ocean, so small and dispersed that early explorers from Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, seeking new westerly routes to the Spice Islands by going around Tierra del Fuego in South America, could sail right through the archipelagoes and not realize that there was any land (relatively) nearby. The famous explorer Ferdinand Magellan did just that in 1593, seeing nothing except two tiny atolls. It was he who gave this ocean the name Pacific because just by chance it so happened to be calm when he first arrived. Two years later another explorer Alvaro de Mendana came across the island Fatu Hiva at the southernmost edge of the Marquesas archipelago, itself at the western edge of Polynesia, making him the first European to make contact with the Polynesian people.

And yet, thousands of years ago, the people we now label as Polynesians managed to populate every single habitable island. This raises three major questions: Who are they and from where did they originate? How did they manage to navigate these vast distances and find and populate these remote islands? Why did they undertake these perilous journeys into the unknown across a dangerous ocean?

The book Sea People by Christine Thompson (2019) looks at the efforts to unearth answers to these questions. The simplest and most obvious way to answer them is of course to ask the Polynesians themselves. But theirs is an oral culture in which knowledge was handed down from generation to generation in the form of chants and epic narratives that mixed genealogies and myths, often in a non-linear style that was difficult to translate into the linear chronologies that we are more familiar with.

One might think that modern DNA analysis techniques might answer the question of origins but not so since there were multiple population bottlenecks as small groups of people founded new populations on previously unoccupied islands and then mixed with later arrivals that have muddied the waters. Finding DNA of ancient people in burial grounds that might give clues to the original inhabitants is also not easy because the conditions on the islands are not conducive to preserving the DNA of bodies in burial sites, coupled with the reluctance of people to allow scientists to dig up what they consider the sacred burial grounds of their ancestors.

Since the Pacific ocean is so vast and the islands that dot it so tiny, it seemed incredible to western explorers and anthropologists that the island populations could have been the result of planned colonization by people who deliberately set out on the journey from either some part of Asia and went east or from South America and went west. Since both models had problems, some early suggestions were that the people originated on the islands themselves, an idea that is now of course rejected in the light of our knowledge of human evolution. The problem is that while linguistic and other ethnographic indicators suggest Polynesians originated in the Micronesian and Melanesian regions and thus must have traveled eastwards across the ocean, the trade winds that are dominant in the equatorial and tropical regions blow from the east to the west which would have made that route very difficult. There are so-called ‘westerlies’ that blow in the opposite direction but those are close to the polar regions far north and south of the Polynesian triangle. (p. 39)

Some have suggested a ‘Beringian theory’, that they did go eastwards in the far north near the Bering Straits and then looped back in the opposite direction using the trade winds. But such a long circuitous route is judged to be unlikely. That led to suggestions that the Polynesians came from South America and took advantage of the trade winds to travel in a westerly direction. The most famous proponent of this view was Thor Heyerdahl and his Kon Tiki project, where he and five others set off in 1947 from Peru on a large raft made of balsa wood. Three months later, they reached the island of Raroia in the Tuamotu archipelago, seemingly having proved their hypothesis.

The Kon Tiki expedition received massive publicity and cemented in the public imagination that this was how Polynesia was populated, an impression that remains to this day. (In my middle school in Sri Lanka, Heyerdahl’s book The Kon Tiki Expedition was one of the readings.) But its central thesis has been rejected by pretty much every scholar because the counter-evidence is so great that Polynesian roots were not from South America. As Thompson writes (p. 240), “virtually all Polynesian food plants and domesticated animals and the well-established linguistic arguments” suggested that they came from Asian region. The people of the islands had dog, pigs, and chickens, all of which were unknown in in South America at that time. (The one exception is the sweet potato which is from the Americas and its presence on the islands remains a puzzle, with various speculations including the suggestion of natural long-range dispersal of seeds.) As one critic wrote, Heyerdahl’s arguments could not be supported “chronologically, archaeologically, botanically, racially, linguistically, or culturally”. (p. 245). Other critics point out that Heyerdahl rigged the experiment by first having his raft towed out fifty miles to sea so that they could catch the Humboldt Current which then took them to he South Equatorial Current that would sweep them along the direction they sought. They also took with them modern navigational instrument such as the compass, sextant, and charts to work out their position, as well as a radio.

So if the early Polynesians came from the other direction, how did they overcome the opposition of the trade winds? While they were expert canoe builders, making large, stable seagoing vessels that could carry over a hundred people as well as dogs, pigs, and chickens (and rats), the opposing winds were a formidable obstacle. Computer simulations suggest that simply drifting along and trusting to chance has almost zero chance of success in reaching an island. But if one introduces a slight navigational advantage to the simulations, that can be done. The catch is that the ancient navigational lore that was handed down orally from generation to generation is in danger of being lost but enough remains that we know it can be, and now has been, done. What is required is detailed knowledge of the stars in order to navigate, the ability to read oceans currents and swell patterns to sense directions, and the patience to wait for occasional changes in wind direction and take advantage of them. One technique is to watch for birds, since different species can travel for different distances. In the mornings, birds travel away from land and in the evenings they travel back to land so observing birds can be an aid. Inter-island crossings have now been demonstrated by expert navigators, using these ancient techniques that involved nothing but knowledge about the “stars, winds, and swells, could hold a course, calculate the distance traveled, hit a target with sufficient accuracy, and incorporate all the necessary information into a mental construct that was both flexible enough to allow for adaptation and systematic enough to be passed on.” (p. 294)

The question of when these migrations occurred has been studied extensively and the dates have shifted over time. The islands of what is known as western Melanesia, consisting of New Guinea, Bismarck and the Solomon Islands have been occupied for tens of thousands of years, much longer than the Polynesian islands. New Guinea and Australia were once joined by a land bridge and were settled at least 40,000 years ago. (p. 197) The current dominant theory based on excavations of pottery and other archeological artifacts is that the so-called ‘Lapita’ people (named after a village in New Caledonia that lies east of Australia) went eastward and reached Samoa and Tonga (on the west edge of the Polynesian triangle) around 900 BCE. This eastward migration then stalled for a long time and then there was a new and sudden further eastward expansion to central and eastern Polynesia around the end of the first millennium AD, with a looping back west to New Zealand around 1200 AD.

The final question is why the early Polynesians undertook these hazardous journeys into the unknown in search of land that they could not know even existed. That is the most difficult to answer, since it speaks to the motivations of long ago peoples. The reasons that people undertake such dangerous migrations now (such as over-population or fleeing persecution and poverty) that result in tragedies like the large number of deaths due to overloaded refugee boats sinking in the Mediterranean may not apply. There is always the option of people seeking adventure, the thrill of heading out into the unknown and unexplored, and Polynesian culture definitely has that streak of romanticism, but such risks are not usually taken by large numbers of people carrying livestock along with them.

Thompson suggests that there could also be another factor at play, which is that of the importance of founders in their culture.

Many Austronesian cultures show a deep reverence for founder figures; this is certainly true in Polynesia, where lineages are named for founders whose names and deeds are the very backbone of the mythology. Founders hold positions of rank and command material advantages, and over time those benefits accrue. As one anthropologist put it, the original settlers of New Zealand, whose journey constitutes the final chapter in this great migration, “would have been heirs to perhaps 3,000 years of successful Austronesian expansion” – three thousand years of founder tales “stacked one upon the other.” Under such circumstances, what “ambitious young man of a junior line” would not seek to become a founder himself by setting off in search of his own island, no matter how far away? (p. 233)

There is still a lot we do not know as well as some uncertainty about what we think we know about the Polynesians. I had not thought a lot about the origins and history of the Polynesians, except incidentally from those accounts that used those islands as settings. The places such as Tahiti, Bora Bora, Fiji, Samoa, Pitcairn Islands, and Tonga sounded idyllic in those accounts but the Polynesian people formed mainly a backdrop to the events described. Thompson’s book was helpful in combating my ignorance and I now have a much greater appreciation for the abilities of these peoples who had such high levels of endurance, knowledge, perseverance, and skills to be able to achieve such tremendous feats of navigation over a vast ocean.

Fascinating stuff, Mano. I’m going to try to get hold of a copy of Thompson’s book.

Incidentally, the instrument you call a “sexton” is probably actually the sextant.

[You are right. I have corrected it. Thanks! -- Mano]

The triangle looks like a pyramid, so obviously it was aliens wot dun it.

The language families seem to have their origin on the east coast of Taiwan. But genetically the peoples are not related, so there must have been a “language transfer” episode between unrelated groups. The most westerly member of this language group is Madagascar.

Back in the 1970s, a Polynesian double-hulled voyaging canoe called the Hokule’a sailed from Hawaii to Tahiti using the stars as navigation. This was the first voyage of the Polynesian Voyaging Society. Their website is https://hokulea.com/

They have a lot of information they’ve collected about the early Polynesians.

I wonder what percentage of exploration and then settlement expeditions succeeded.

Holms @#5,

I wondered about that myself. It is probably something that we will never know. It is possible that small groups of adventurers first went out on their own and those who found new islands and were able to return then took with them larger numbers of people and livestock on bigger canoes to create settlements.

I used to be impressed with space “exploration”.

But every single person who went into space, ever, had behind them a team of tens, even hundreds of thousands of experts, scientists, mathematicians, engineers, technicians, manufacturers, project managers. They had a significant share of their entire country’s GDP to spend, and the countries in question are few and rich. And lest we forget, space is not remote -- space would be barely a couple hours’ drive away in a normal family car, if you could drive it straight up -- and you can see the destination from basically any point on earth.

The Polynesians, wherever they came from, had almost nothing behind them, no advanced economy or technology supporting htem, and struck out across a hostile environment towards targets which they can’t possibly have known were even there. They’re the most impressive explorers in human history. I find it hard to even really understand the level of their achievement in settling the Pacific.

I tend to be a bit dismissive of those modern “we reenacted an ancient polynesian voyage” exercises. Sure, you knew that there was an actual destination, not that you were sailing into the unknown. And the winds and currents are understood, too. You don’t risk sailing into the doldrums and dying of thirst or scurvy.

I used to wonder how many deep sea voyages happened because of a navigation error -- “oops we missed the island and now we are headed who knows where.”

Mano, thanks for the essay!

#8 Marcus

They probably also had a satellite phone or similar, not used generally but there just in case.

Yes they had pretty incredible abilities (and guts, plenty of those).

Another thing I once read was that, once the sea routes between islands had become established, a way to find and follow them was to follow sharks.

It seems that after the humans found the way, sharks found them too and tended to linger along those routes, eating what was thrown off the boats. So during the day, instead of the stars you followed those fins…

Dunno it it’s really true, but it’s a smashing good yarn.

@8, @10: the first Polynesian Voyaging Society ship launched in 1973. The first satellite phone launched in 1989. Even if you know there’s land ahead, you still have to get there.

Another point: the first people of Australia voyaged to get there, too.

The ice age which lasted 90,000 years and ended 10,000 years ago has to be taken into account when talking about human migration because the ocean levels were estimated to be 25-50 metres lower, possibly more. Underwater pronouncements today may have been islands and single islands now archipeligos for millenia. Thousands more islands and the plants, animals, and water sources that were on them would have provided more living space, more resouces, and shorter trips between islands during Polynesian migration.

The Taiwan Strait’s depth is about 50 metres, and many of the animals here in Taiwan crossed dry land from China when the waters receded; they are the same species of animals. The sika deer (also found in Korea and Japan), mountain cat, formosan black bear and mountain dog couldn’t have swum here. The Timor Sea between Indonesia and Australia is roughly the same depth as the Taiwan Strait. People could have walked to Australia and Tasmania, and didn’t need boats.

Look at the ocean depths around the South Pacific and Indian Ocean on the link below. The potential island chains are extensive: Solomons to Vanuatu and New Caledonia, east to Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, and French Polynesia. It’s only 1500km from French Polynesia to Gambier, 700km to Pitcairn, 400km to Ducie Island, and then 1500km on the last leap to Hanga Roa (Easter Island). Another potential chain goes north from French Polynesia to Kiribati and the Johnson Atoll. Then it’s only 1500km to Hawaii.

Island hopping west to Madagascar would be the hard part, but not impossible: Sumatra to Sri Lanka, the Maldives, Chagos Archipeligo, Mascarene Islands (the now underwater Mascarene Plateau), and then Madagascar.

https://serc.carleton.edu/eslabs/corals/4b.html

Another factor about lower the water levels during an ice age is less severe the waves. Shallow water (and the protection of islands) mean less severe waves than deeper water. And a cooler Earth means fewer typhoons, making ocean travel safer.

Holms (#5) --

The ant theory of migration. A worker goes out and leaves a chemical trail. If a food source is found and it returns to the nest, the others follow. If they don’t return, don’t go. I’m not being flippant, it makes sense.

Intransitive, according to the OP much of the exploration and settlement of Polynesian islands happened during the last 3 millennia, so well past the ice age.

To seek more land, presumably, because there was a limited amount for the society at home. To found a clan, to settle a new homestead.

The first few times, sure, trepidation and/or great need. After that?

We know there was an oral tradition, so this became a custom, a thing that was done. They’d done it before, they could do it again.

Surely it was not a low-status undertaking.

anat (#14) --

3000 years before present is the latest possible date, not the earliest. PNAS, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences published this:

@ ^

That’s not Polynesian. Solomon Islands can be clearly seen in Mano’s graphic just above the label Melanesia.

@ 7 sonofrojblake

This is an astoundingly stupid thing to say. The barrier is not, of course, distance, but velocity. Orbital velocity is about 30 km/s, or roughly 90 times the speed of sound.

Another possible factor; a window of wind opportunity;

https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/news/2014/10/polynesian-migration-mystery-solved/

Silentbob @18: The orbital speed of the Earth around the sun is about 30 km/s. For low spherical orbit around Earth, it’s about 7 km/s, and drops as 1/√R as orbit radius R increases. Escape velocity from Earth’s surface is about 11 km/s.

I wouldn’t say that mistaking orbital speed around the sun with orbital speed around Earth is astoundingly stupid, but I’m a polite fellow.

#13 Intransitive

I don’t find the sea level change very compelling. Very few seamounts have a peak so close to the surface, I think the colour gradient of that map is deceiving you.

In response to #18:

“This is an astoundingly stupid thing to say.”

That’s your opinion.

The Observer newspaper made the original statement their saying of the week in September 1979, and it’s in the Oxford Essential Quotations 6th edition. It’s a slight mangling (my memory not being perfect) of the words of world famous astrophysicist Fred Hoyle. https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/acref/9780191866692.001.0001/q-oro-ed6-00005651;jsessionid=76026D71FEF1423C179A648B539ADFC7

We can add this sage opinion of yours to other recent gems like Marlon Brando and Dustin Hoffman being the same guy, and all homophobia in history being the fault of the Jews. You’re quite the font of wisdom.

sonofrojblake, space is not quite the same as the open pacific ocean, where one has temperate temperature (heh), air, gravity, and of course sources of food and water.

(Not really comparable)

There is a large area of submerged land known as Sundaland, which was wholly exposed during the last glacial maximum, and was slowly submerged between 12,000 bce to 3000 bce.

I assume that drove some people to build boats, develop a maritime culture, and migrate.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sundaland

Perhaps one more thing.

Actually, they had pretty good technology; I’ve seen exhibits in Australian museums and I was duly impressed.

It’s all O so relative; what we now consider advanced technology will in the future be seen much as theirs is seen by you by the typical person

(Not exactly swimming naked into the ocean, were they?)

Thanks for that valuable and perspicacious insight. Really, what would we do without your input?

I reflected on the motivation behind #18. Obviously Silentbob missed the point entirely, and instead had a thought process something like “I KNOW A THING! I KNOW A THING! I HAVE TO SHOW I KNOW A THING!”, regardless of whether said thing is relevant. This, on its own, is a bit sad and needy. “I’m ignoring the metaphor you quoted (and calling it stupid without recognising the source) so I can show off my great knowledge” is a depressing thing to do.

But to then have it immediately demonstrated that what you thought you knew isn’t even correct? That’s past sad and into tragic. What a shame. (and for Silentbob’s benefit, just in case: https://www.google.com/search?q=dictionary+shame )

sonofrojblake,

Dunno about ‘we’, but you would certainly still imagine that the two are somehow comparable. Your thanks are meet, and it becomes you.

I have agonised over whether to do so but I feel this is probably a safe subject for me to re-engage with here, being myself of Polynesian descent with a childhood spent in a Micronesia.

Mano, thank you for your open appreciation of the achievements of the Polynesians and other sea faring Pacific peoples.

This will be a bit disjointed. Sorry in advance. It is a bit of a brain dump. And, I actually find it very difficult to explain. Perhaps reading on you might understand why.

We did indeed have something behind us.

Oral traditions among indigenous peoples are those of song and dance. The songs are embedded in the memory through dance from a very early age and are sung and danced right through to old age. In the same way you remember your childhood nursery rhymes that you sang and danced; the memory is locked in and can be passed on unchanged from generation to generation. Everyone who danced them can still recite the “ring a ring o’ roses”, “incy wincy spider” or “put your left foot in” rhymes of their childhood, but imagine if you had sung and danced them, with all of your community, daily, all through your life?

The ancestral songs have ever deeper levels of meaning that are revealed as we age into our traditions.

Our ancestors were sung up to the stars where they travelled through the constellations on their final journey. These paths travelled by the ancestors between the constellations are in fact the pathways across the ocean from island to island.

When your island is only a few square kilometres of dry earth, and your people are spread across dozens or even hundreds of islands, the stars become your map.

What you call navigators we call way finders. They don’t navigate, they follow the ways mapped in the stars. The ways are like an anchor rope, with the islands at the end of the rope waiting to be pulled out of the ocean.

With their oral star chart, along with acute observation of swell and wave, the movements of birds and cetaceans and other subtle signs, through their deep connection to the physical world my Polynesian ancestors were as at home on the open ocean as you now are on the freeways.

An easterly prevailing wind lends itself to a safe eastward exploration. A week of tacking against the prevailing wind is a simple 2-day return trip home if you find nothing.

Why the continued exploration and expansion? Probably shortage of resources and ensuing conflict more than anything else. Humans are like that.

I cannot recommend this film highly enough. Whetū Mārama -- Bright Star . Sorry but it is not free to watch, but will cost a few dollars to rent online.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hector_Busby

Hekenukumai Ngaiwi Phuipi -- Hector Busby -- is from the same Northland area area of Aotearoa that my father was from. Coopers Beach. I have never been there. My father’s connection with his ‘tribe’ was broken as a child when he had his ancestral language beaten out of him by god-fearing xian schoolmasters. I am therefore second-generation dispossessed. My ancestral heritage is like a vague memory of a fleeting dream. It is to this day a deep and enigmatic thread of sorrow running through my life that I cannot pick out lest I unravel myself. It confuses and saddens me even as I get strength from it.

So, yes, we did have something behind us. We had thousands of years of accumulated knowledge of the ways of the ocean, this deep ancestral knowledge embedded into the natural world with mythology. We were at home on the open ocean a thousand kilometres from the nearest land at a time that many of the ‘civilised’ people of Europe were allegedly afraid of venturing beyond the horizon.

Technology isn’t just in the form of physical tools. One of humanity’s oldest tools, and I would argue the most powerful, is the ability to conceptualise abstract connections. This is what I understand to be the ancestral dreaming. It is a conceptual framework with which we once stored our knowledge directly in the natural world and is one of humanity’s greatest achievements, allowing groups such as the aboriginal peoples of Australia to sustain a continuous culture for more than 60 thousand years , or the Polynesians to not only populate but to travel freely back and forth between thousands of tiny islands scattered across the largest open body of water on the planet, to name but two.

We need this tool now more than ever IMO.

That is my take on this subject from a less remote but still removed POV, for what little it is worth.

@28 -- post 26 was something humans call “sarcasm”. Look it up. I suspect a great deal of things said to you here and elsewhere are said in this tone, which you demonstrably have trouble recognising.

tuatara, thanks for that.

(Kia kaha tatou — and may I add the Māori were warriors: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s6QhW5S8Gk4 )

@30: “@28 — post 26 was something humans call “sarcasm”.”

Heh. Heh heh heh. heheheheheheheh.

(The irony is most delicious!)

@ 29 tuatara

Wow. Awesome comment; thanks for explaining. It’s so much better to hear from someone connected to the source than some academics opining from afar.

John Morales. Cannibals too!

tuatar @#29,

Wow, thanks so much for that post! It was extremely helpful in fleshing out what I had written.