Animated gif, so below the fold to spare everyone the constant distraction.

Animated gif, so below the fold to spare everyone the constant distraction.

Did you know cephalopods may have traded evolution gains for extra smarts? I didn’t either. I don’t believe it, anyway. The paper is fine, though, it’s just the weird spin the media has been putting on it.

The actual title of the paper is Trade-off between Transcriptome Plasticity and Genome Evolution in Cephalopods, which is a lot more accurate. The authors discovered that there’s a lot of RNA editing going on in coleoids. The process is not a surprise, we’ve known about RNA editing for a long time, but the extent in squid is unusual.

RNA editing is basic college-level stuff, so if your experience in biology is limited to high school classes or pop press summaries, you may not be familiar with it, so a quick summary follows.

There is a small family of enzymes in vertebrates called the ADARs, or Adenosine Deaminases Acting on RNA. These enzymes bind to double-stranded RNA, and convert the adenosine bases to inosine. Inosine preferentially base-pairs with cytosine, so this functionally converts the As in the double-stranded stretch into Gs.

There are limitations on this enzyme, so it doesn’t charge off and convert every A in every RNA into a G, which would be lethal! Since it only works on double-stranded RNA, which requires that the sequence of the RNA be such that it can fold back on itself and create regions where long bits of the sequence are binding to itself, it only works on some RNAs. This requirement also means that in some ways it is evolutionarily and genetically fragile — mutate a base somewhere in that dsRNA stretch, and it stops being double-stranded, and the enzyme no longer converts A to G.

Before the creationists and ID creationists get all excited, this is not revolutionary, and does not in some way preclude evolution. The presence of these enzymes means that there is an alternative way to tweak some bases in a sequence other than by directly modifying it by mutation in the genome. In a simplistic way, you can just think of it as another way a single-base pair mutation can occur — it’s just done in the transcriptome, rather than the genome.

It also has some advantages. Because the enzyme is not perfect, some RNAs escape the modification, which means the organism can have both the unedited and edited forms of the protein — so if the unedited form performs some useful function, that function hasn’t been eliminated in one swoop. It may provide a kind of soft transition between two forms of a protein.

There is also a disadvantage. Because the formation of double-stranded RNA requires the maintenance and cooperation of multiple bases in multiple regions of the sequence, coming to rely on RNA editing for one base can lock in the sequence of multiple other bases. That’s the meaning of the title of the article: the tradeoff is that yes, you can get a useful adaptive modification by modifying the transcriptome (transcriptome plasticity), but if you’re dependent on that, you’ve also limited the amount of change you can tolerate in associated regions of the genome (genome evolution). There is basically a window around the change you want that is approximately 200 bases long that you now have to constrain in order for your key change to continue to work.

That’s limiting. The authors point out that only about 3% of human RNA messages are recoded by ADARs, and only about 25 total are conserved across mammals. That implies that a lot of the RNA editing going on is spurious, but some tiny part of it is functionally necessary.

In contrast, some cephalopods, the squid and octopuses, have many more.

The authors searched for non-synonymous sequences between RNA and DNA. They found lots, and further, the A-to-G mismatches, which is what you’d expect if this were a result of ADAR editing, were greatly enriched. Most importantly, they compared multiple species, and only the coleoids exhibited this pattern, while Nautilus and Aplysia did not. This is a property of the organisms, not an artifact of their methods.

So how many sequences are modified by ADARs in squid? That’s tough to determine, since we know there will be spurious editing all over the place, but we can say confidently that it’s orders of magnitude more than what is seen in humans. The most relevant and conservative estimate in the paper is that “1,146 editing sites (in 443 proteins) are conserved and shared by all four coleoid cephalopod species”. Compare that to the 25 in mammals.

Also interesting is that the sequences identified are often developmentally and neurobiologically significant. Protocadherins (molecules involved in cell adhesion, and therefore important in the development of multicellular animals) were enriched both in overall number and in RNA editing sites. They also specifically compared the function of neuronal channel proteins in both the edited and the unedited versions. The unedited proteins were still functional, but the edited versions were more sharply tuned in their electrical properties.

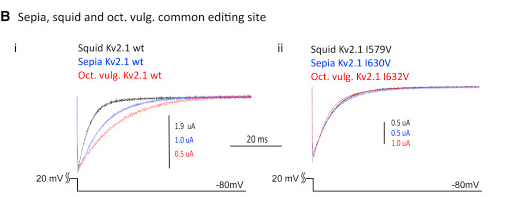

Here’s an example. They recorded the potassium current for unedited K+ channels on the left, and for edited channels on the right. These are conserved editing sequences maintained in squid, cuttlefish, and octopus, and you can clearly see that editing removes differences between those species to produce a more similar pattern of current flow.

Conserved and Species-Specific Editing Sites Affect Protein Function

Unedited (WT) and singly edited versions of the voltage-dependent K+ channels of the Kv2 subfamily were studied under voltage clamp.

(B) (i) Tail currents measured at a voltage (Vm) of −80 mV, following an activating pulse of +20 mV for 25 ms. Traces are shown for the WT Kv2.1 channels from squid, sepia, and Octopus vulgaris. (ii) Tail currents for the same channels edited at the shared I-to-V site in the 6th transmembrane span, following the same voltage protocol.

That we’re seeing changes in nervous system activity is probably why the first article I cited seems to think this has something to do with making cephalopods smarter. It doesn’t, directly. It’s more that one of the mechanisms driving the cephalopod radiation after the Cambrian was adoption of modification of the transcriptome via RNA editing. It’s a pattern that isn’t easily reversed — a lot of proteins would have to be tweaked at the genome level to make them independent of ADARs — but it works, so there’s no particular pressure on them to modify the mechanism.

Liscovitch-Brauer, Noa et al. (2017) Trade-off between Transcriptome Plasticity and Genome Evolution in Cephalopods. Cell 169(2):191-202.

I am about to revolutionize the academic experience, which is afflicted with endless committee meetings, inspired by this comic:

I’m switching it around. No more meetings wrecking my days. Instead, all committee meetings are to be immediately replaced with “drinks”.

The only problem is that some days I have so many meetings I might suffer from alcohol poisoning.

Our weapon is piety and sanctimony. No, our two weapons are piety, sanctimony, and hypocrisy. Our three weapons are piety, sanctimony, hypocrisy, and a whole lot of bombs. Trump must have thought it was wonderful that he had an opportunity to wrap himself up in the flag and babble about god.

My fellow Americans, on Tuesday Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad launched a horrible chemical weapons attack on innocent civilians. Using a deadly nerve agent, Assad choked out the lives of helpless men, women and children. It was a slow and brutal death for so many. Even beautiful babies were cruelly murdered in this very barbaric attack. No child of God should ever suffer such horror. Tonight I ordered a targeted military strike on the airfield in Syria from where the chemical attack was launched. It is in this vital national security interest of the United States to prevent and deter the spread and use of deadly chemical weapons. There can be no dispute that Syria used banned chemical weapons, violated its obligations under the chemical weapons convention, and ignored the urging of the UN Security Council. Years of previous attempts at changing Assad’s behaviour have all failed and failed very dramatically. As a result, the refugee crisis continues to deepen and the region continues to destabilise, threatening the United States and its allies. Tonight I call on all civilised nations to join us in seeking to end the slaughter and bloodshed in Syria, and also to end terrorism of all kinds and all types. We ask for God’s wisdom as we face the challenge of our very troubled world. We pray for the lives of the wounded and for the souls of those who have passed, and we hope that as long as America stands for justice, then peace and harmony will in the end prevail. Good night and God bless America and the entire world. Thank you.

Assad is a vile piece of shit, I agree. Killing civilians, or anyone for that matter, with nerve gas is a crime against humanity, and something should be done…I just don’t know what, except that wrecking a country with a hail of missiles doesn’t seem to be a very practical way to protect “beautiful babies”. It’s also not just Trump — Obama seems to have killed a lot of civilians with drone strikes, and clearly both parties are blithe about murdering foreigners.

And now I’m also confused by the Trumpian incoherence, which doesn’t help.

You know Syria is one of the countries under a travel ban — and Trump campaigned on opposing immigration and banning those “beautiful babies” from entering the US.

The United States’ record on allowing those “beautiful little babies” of Syria — and their battle-scarred parents — to come here as refugees from the war zone has been abysmal. Over one roughly equivalent stretch of time last year, our next-door neighbors in Canada took in 25,000 Syrian refugees while America took a paltry 841. Hillary Clinton pledged to increase that number — not dramatically — and she was savaged on the campaign trail by Trump and his supporters. Trump, of course, announced a ban on accepting refugees as part of his sweeping — and struck down — travel ban.

It’s also the case that only a few years (months?) ago, Trump was howling in opposition to any military intervention in the region.

AGAIN, TO OUR VERY FOOLISH LEADER, DO NOT ATTACK SYRIA – IF YOU DO MANY VERY BAD THINGS WILL HAPPEN & FROM THAT FIGHT THE U.S. GETS NOTHING!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 5, 2013

It also means that he has thrown away all the cards in his hand and seems to be asking for a new deal.

He was pals with Putin; throw that away, because Putin is an Assad ally and is now talking about beefing up Syria’s defenses.

One of the reasons Trump hadn’t leapt into action before was that the openly hated ISIS was also fighting against the Assad regime. We are now allied with ISIS, in this one thing!

This one is almost amusing: Pepe the Frog is most unhappy with Trump. Milo Yiannopoulos, Richard Spencer, Gavin McInnes, Mike Cernovich, Charles Johnson, and Stefan Molyneux — among the most horrible awful people on the planet — are united in condemning the FAKE, GAY

bombing. No word yet on Martin Shkreli’s opinion. I’m allied with these trolls, on this one thing? I’m feeling nauseated.

It’s total chaos!

And look at the flagrant embrace of god-talk in his last three sentences, the usual first resort of American politicians leaping into destruction. I don’t know what god he’s appealing to, but I’m beginning to suspect that it’s Arioch. Blood and souls! Blood and souls for Lord Arioch!

And he deserves every glittering sunbeam. This is Cernovich.

This is the "alt-right" troll the Trump White House is touting https://t.co/JuUJq6dy6q pic.twitter.com/2eVHtiFjLK

— Media Matters (@mmfa) April 5, 2017

He got to appear on 60 Minutes, which has led to more media exposure.

Cernovich’s allegiance to the “alt-right,” a self-descriptor for a faction of the white nationalist movement, has been repeatedly documented. In 2015 he explained, “I went from libertarian to alt-right after realizing tolerance only went one way and diversity is code for white genocide.” Additionally, in a series of since-deleted tweets, Cernovich declared that “white genocide is real” and “white genocide will sweep up the [social justice warriors].” Cernovich also traffics in sexist rhetoric, having claimed that “date rape does not exist” and “misogyny gets you laid” and said that people who “love black women” should “slut shame them” to keep them from getting AIDS.

Cernovich has also helped popularize numerous conspiracy theories, including the “Pizzagate” story that claimed an underground child sex trafficking ring was run out of a Washington, D.C., pizza parlor and involved top Democratic officials. Despite widespread debunking, Cernovich recently claimed that the restaurant was a place “where a lot of pedophiles meet.” He often uses conspiracy theories to weaponize his social media following against his critics, such as when he baseless claimed satirical video editor Vic Berger was a pedophile after Berger published videos mocking Cernovich.

The New York Times recently published an article answering the question “Who is Mike Cernovich?”; the cliff notes version of the answer is simply: he is a bad guy. For anyone willing to look for evidence, it isn’t hard to find; Cernovich’s lies are all readily accessible on his own social media, not to mention a documented fact from both conservative and liberal sources alike.

I’ve also been targeted by the lies of Cernovich. My crime: I pointed out that he was completely wrong about HIV when he claimed If you’re a straight man, you will not get HIV.

So he accused me of raping a student. No, he didn’t just accuse me: he made up the detailed and totally imaginary testimony of the student confronting me.

Using psychodramatic techniques, I will tell the story of PZ Myers’ alleged rape victim, as best as I can. (I have not spoken to the alleged victim. Rather, I am imagining and channeling what she might have felt, said, and experienced.) TRIGGER WARNING: This will be very disturbing.

He’s a fucking lawyer. He included this confession that he was openly lying to provide an excuse if he was sued (I obviously wasn’t claiming that he had actually done this, your honor

), but no one is fooled. He’s a liar.

I guess if you lie big enough you get an episode of 60 Minutes and a mob of fascist defenders as a reward.

I’m never going to be a fan of a story of a hearing that is titled Eyewitness to a Title IX Witch Trial — it’s loaded with language that is prejudicial and ignores the facts, from the title onward. “Witch trial,” really? It’s the story of a philosophy professor, Peter Ludlow, who was accused of taking advantage of a student. The story states the facts quite clearly, but then goes on to assume the professor was innocent. Here’s what we absolutely know, because both sides agree to this account.

Ludlow and the student, whom I’ll call Eunice Cho, spent the evening going to gallery openings and bars, then ended up sleeping together, clothed, on top of the comforter, in a bed at his apartment. They agree that they didn’t have sex, but Cho would charge that Ludlow had forced her to drink liquor she didn’t want and had then groped her, both at a bar and at his apartment, which led to her trying to kill herself a few days later. Cho filed a Title IX complaint; then hired a lawyer and sued both Ludlow and the university for monetary damages. Ludlow countersued for defamation.

I’m going to say right there that Ludlow was in the wrong. Getting drunk with a student? Bringing her back to your home? Sharing a bed, even if sex didn’t happen? Damned poor judgment on Ludlow’s part. I cannot imagine ever doing anything like that — a student, at an event on my invitation, who was getting drunk…that’s where you stop the situation cold, not hours later when you’re both passed out in bed. This is an action by a professor that warrants discipline.

Then more problems are exposed.

When Cho’s lawsuits went public, a graduate student I’ll call Nola Hartley came forward. Ludlow and Hartley had had what was, at the time, a consensual three-month relationship some two years earlier. Hartley now charged that Ludlow had raped her on one occasion when she was asleep in his bed after drinking too much, though she didn’t actually remember it happening. (They had sex on another occasion, she acknowledged, but that was consensual.) Hartley had also decided, in retrospect, that the entire relationship with Ludlow had never been consensual. She was 25 at the time, well over the age of consent.

Good grief. He had a sexual relationship with a grad student in his department? This faculty member spells trouble all around. This author is also trouble. The fact that the accuser was over the age of consent says nothing about whether the relationship was consensual — when a woman turns 21 it does not mean she has suddenly agreed to everything. You can be 25, 50, or 80 and still refuse consent to sex.

A surprisingly large chunk of this story is also focused on a character witness who was brought in to testify about how wonderful and charming Ludlow is, sentiments the author clearly shares.

Wilson had known Ludlow for 15 years, she said, first as his student and then in two departments as a colleague, and spoke movingly about him as a mentor and a person. Being around him had been a sort of “effervescent philosophical situation” for Wilson and her then-boyfriend, also a philosopher, when they were all in the same department. When she and her boyfriend decided to get married, they chose Ludlow as the officiant “because he was the most erudite, witty, wonderful person that I knew.”

Yes? So? A psychopath can be witty and charming, that doesn’t mean they are innocent of ever committing any wickedness. I can well believe that Ludlow had a perfectly appropriate, reasonable professional relationship with this witness, and even that the witness had never heard a word of complaint about Ludlow — I’ve been in that same position where I’d been stunned to learn people I thought well of were perfidious scumbags in other relationships. It happens. It also actually supports the complaint by Hartley that she hadn’t been in a consensual relationship: she’d been snowed by a charismatic charmer, as Ludlow apparently is.

The story takes a weird turn with the author’s response to the witnesses testimony.

It probably sounds bizarre to say, given the circumstances, but it felt as if there was an erotic current in the room. It reminded me of my own student days, when the excitement of learning made me feel alive in such profoundly creative, intellectual, erotically messy ways — which were indistinguishable from one another, and no one thought it should be otherwise.

WTF? This is a hearing, which she already characterized as a witch trial, and now she’s talking about an “erotic current”? Jesus. I guarantee you the lawyers didn’t feel that way on either side, nor did the defendant who was trying to protect his career, nor would any of his accusers. This was a hearing, a terrible tedious committee meeting with significant consequences. It sounds like someone was enamored with Ludlow.

By the way, this was serious business. The hearing stretched over a month, with lawyers and peers reviewing the evidence. Here’s how it’s characterized:

It was the campus equivalent of a purification ritual, and purifying communities is no small-scale operation these days: In addition to the five-person faculty panel, there were three outside lawyers, at least two in-house lawyers, another lawyer hired by the university to advise the faculty panel, a rotating cast of staff and administrators, and a court reporter taking everything down on a little machine. Ludlow had his lawyer (and on one occasion, two).

How would the author prefer this be handled? The accusations were serious, the impact on the defendant substantial, and there was a massive investment in addressing them formally and seriously. It was not the kind of thing where it would be appropriate to flippantly dismiss either side — the young woman was distressed enough to have attempted suicide, the professor was at risk of losing his tenured position and his career. Damn right it was going to be handled with due attention to all the details. It was actually overkill in giving due process to a faculty member who had essentially admitted to gross impropriety with at least a couple of students, and the conclusion was essentially foregone once he’d admitted to the behavior, even if he does believe that he has sexual privileges with students because he’s erudite and scholarly. That’s not a “purification ritual”, that’s granting the professor full opportunity to justify his actions.

He lost, too. The author even admits, in a roundabout way, that he’s guilty.

Yes, Ludlow was guilty — though not of what the university charged him with. His crime was thinking that women over the age of consent have sexual agency, which has lately become a heretical view on campus, despite once being a crucial feminist position. Of course the community had to expel him. That’s what you do with heretics.

Goddamn. This is not about the age of consent. It’s not about a 60 year old man having having consensual relationships with younger women. It’s about a power differential, and how someone in a position of greater power can abuse it. He was not a heretic, just a professor who took advantage of students. That’s an already difficult situation, and he made it worse by stupidly getting a student drunk and traumatizing them.

He got a fair and perhaps even too deferential hearing, and his poorly thought-out behavior led to his own resignation.

I have to admit, I sometimes wonder if they were all raised by Harry Harlow’s fake mothers made of chicken wire and cotton, because they sure seem to be lacking in something. This guy at the Federalist, Hans Fiene, has an essay that reads like something from an alien.

The latest numbers on American birth rates are in, and they yield only one reasonable conclusion: All of us need to start having more babies or else the upcoming demographic tsunami will consume our nation, cripple our social programs, and leave us with a future so bleak that our only source of joy will be the moment we’re chosen to receive the sweet, fatal kiss of the Obamacare Death Panels, the Trumpcare Firing Squads, or the OprahCare Hemlock Squadrons.

We do not have a problem of underpopulation — we’re doing just fine, maybe growing too fast for our environment. The “demographic shift” is merely the typical natural change in a population over time. There was an era when there were relatively few Irish in North America, and now there were lots of people of Irish descent. It wasn’t a tsunami, it didn’t cripple us. It’ll be the same with an increase in the proportion of Latin and black families — we’ll be fine. There is a kind of demographic tsunami that would be destructive, like the one that overwhelmed the Indian population of this continent, but there’s no threat of that. Maybe Mr Fiene has a guilty conscience?

Maybe the real problem is his use of the word “us” — it doesn’t seem to have the same inclusive meaning to him that it does to me. He’s using the racist “us”, referring to only people with his skin color.

What is his solution to the “tsunami”? He wants “us”, you know, the white “us”, to have more children than the brown “them”. How does he hope to do that?

Perhaps I’m overstating the danger a bit, but the point remains: Americans need to raise our sagging birth rates. One of the best ways we can do so is by reversing the trend of Americans waiting longer to get married. So, apart from tearing down America’s institutions of higher education, which tend to slow down the recitation of wedding vows, how do we do that? It’s quite simple. We tear down the Friend Zone.

But we Americans don’t have a sagging birth rate…oh, wait, he’s using the racist version of “Americans”, that doesn’t include every American citizen.

I’m relieved that he’s not advocating tearing down universities, but his reasoning is weird. Having children a little later is a fine idea, especially since child-rearing is a difficult and important job that would benefit from a little more emotional and intellectual maturity (trust me, I work with 18-22 year olds all the time, and there’s a huge amount of growth in that span. Because someone is physically capable of getting pregnant at 14 does not necessarily mean they’re mature enough to raise them well…but then, if your vision of parenting is chicken wire and cloth, you may not get that).

Instead, he thinks we need to tear down the Friend Zone. There’s that strange, alien “we” again — now it seems to exclude women. “We” White Men are going to insist that if “You” Women want to have dinner with us, you must also consent to be impregnated.

Every year, countless young men find themselves trapped in the Friend Zone, a prison where women place any man they deem worthy of their time but not their hearts, men they’d love to have dinner with but, for whatever reason, don’t want to kiss goodnight.

Being caught in the Friend Zone is an inarguable drag on fertility rates, as a man who spends several years pledging his heart to a woman who will never have his children is also a man who most likely won’t procreate with anyone else during that time of incarceration. Free him to find a woman who actually wants to marry him, however, and he’ll have several more years to sire children who will laugh, create, sing, fill the world with love and, most importantly, pay into Social Security.

Quite simply, for the sake of our future, the Friend Zone must be destroyed. For the Friend Zone to be destroyed, women must accept the following truths: you don’t have any guy friends and, in fact, you can’t have any guy friends.

I can simplify that rule a lot. Don’t be friends with Hans Fiene, or anyone like Hans. Hans needs to realize, though, that this isn’t a binary situation, where one is either friends with Hans, or is fucking Hans–there is the possibility of accepting neither.

He goes on and on about his fantasy of a world where women either have sex with him or obligingly vanish into the woodwork, never to speak to him again, but I think we get the message. Hans Fiene does not consider women or minorities to be fully human, and not part of his “us”.

Hans is a Lutheran pastor, by the way.

His mother was probably just fine. He just thought she was made of chicken wire.

A topiary thief struck the UNC Charlotte Botanical Garden! This is the victim:

Fortunately, we don’t need to dispatch the Pharyngula vigilantes to hunt down the shrubbery-napper — it’s already been returned, with a nice apology even.

There’s a lot to despise about Twitter, but at the same time, it’s become one of those social necessities, like those calling cards you had to have handy when visiting Victorian homes. But at the same time, Twitter totally sucks. It’s a haven for Nazis and shit-posters and harassers, and Twitter management has zero interest in making it better for users. Another problem is that they don’t seem to have any competition.

So let’s see some! Sarah Jeong explains a promising alternative called Mastodon. It’s similar in function to Twitter, but has a different underlying philosophy, relying on distributed clusters of users called instances, which then share conversations with users you follow more widely. I haven’t figured out all the mechanics yet, it’ll take time. The big difference is that the instances have zero tolerance for fascists, racists, and harassers, and they say so — and they’ll cut you off if pull any of the crap that is routine on Twitter. That sounds good to me!

If you’re interested in trying it out, go to the list of instances and pick one out — they’re rated for their reliability and number of current users. Jeong signed on to mastodon.social, but that one is closed right now, so pick a different one — they should all allow exchanges between one another, so it shouldn’t make a difference, I don’t think. I chose octodon.social, just because something about the name appealed. Don’t know why. I also kind of liked the manager’s rules:

It should be similar to mastodon.social’s.

NSFW/any legal porn is allowed, but tag it as NSFW or make it unlisted or something.

Trolls are only allowed if they’re quiet; you can shitpost but not harass someone, and my threshold is pretty low.

I’m not Twitter, I’ll fuck up nazis and bullies for fun, and get an AI to do it if I get bored.

I’m your nice cyberpunk queen but I intend to keep this place decent and safe for everyone.

So now I’m signed up as pzmyers@octodon.social. I haven’t done anything with it yet — you know the general principle with any social medium, right? Listen for a while before blaring — but the environment seems pleasant, if a little more quiet. The problem with these things is that they require a critical mass of users, or they fall flat and die, so that may happen here, too.

Oh, and another problem: you don’t “tweet”, you…”TOOT”. Ugh. Why do the people who have the smarts to set up this kind of thing always have a tin ear?

Anyway, if you’d like to take a small step in disrupting the Twitter hegemony, try it out.