Within the hour! Tune in!

If you’re one of those genetic determinists who still believes that DNA defines everything about you, you’re especially urged to watch.

Within the hour! Tune in!

If you’re one of those genetic determinists who still believes that DNA defines everything about you, you’re especially urged to watch.

This is more like it. This is how I like to start my mornings: a time-lapse movie of rotting whales in Patagonia. And now you can watch, too.

It’s tragic, but it’s also scientifically interesting. These events have major effects on the local ecology.

If you read Nathaniel Comfort’s scathing review of Robert Plomin’s book, Blueprint, you ain’t seen nothin’ yet. He was holding back, maintaining the decorum of the journal as best he could. He gives a more thorough criticism on his blog, Genotopia, and wow, it’s even more brutal. Sometimes a more thorough and nuanced analysis just leads to an even stronger condemnation.

…Plomin’s argument is socially dangerous. Sure, genes influence and shape complex behavior, but we have almost no idea how. At this point in time (late 2018), it’s the genetic contributions to complex behavior that are mostly random and unsystematic. Polygenic scores may suggest regions of the genome in which one might find causal genes, but we already know that the contribution of any one gene to complex behavior is minute. Thousands of genes are involved in personality traits and intelligence—and many of the same polymorphisms pop up in every polygenic study of complex behavior. Even if the polygenic scores were causal, it remains very much up in the air whether looking at the genes for complex behavior will ever really tell us very much about those behaviors.

In contrast—and contra Plomin—we have very good ideas about how environments shape behaviors. Taking educational attainment as an example (it’s a favorite of the PGS crowd—a proxy for IQ, whose reputation has become pretty tarnished in recent years), we know that kids do better in school when they have eaten breakfast. We know they do better if they aren’t abused. We know they do better when they have enriched environments, at home and in school.

We also know that DNA doesn’t act alone. Plomin neglects all post-transcriptional modification, epigenetics, microbiomics, and systems biology—sciences that show without a doubt that you can’t draw a straight line from genes to behavior. The more complex the trait in question, the more true that sentence becomes. And Plomin is talking about the most complex traits there are: human personality and intelligence.

Plomin’s argument is dangerous because it minimizes those absolutely robust findings. If you follow his advice, you go along with the Republicans and continue slowly strangling public education and vote for that euphemism for separate-but-equal education, “school choice.” You axe Head Start. You eliminate food stamps and school lunch programs. You go along with eliminating affirmative action programs, which are designed to remediate past social neglect; in other words, you vote to restore neglect of the under-privileged. Those kids with genetic gumption will rise out of their circumstances one way or another…like Clarence Thomas and Ben Carson or something, I guess. As for the rest, fuck ’em.

I can see how that wouldn’t get printed in Nature, but he’s exactly right on every single point. Plomin, no matter what his own political views, has written a garbage book that plays right into the hands of the right wing, from the title onwards. It’s shocking that Plomin is completely oblivious to how crude and wrong his understanding of modern genetics is…a lock of understanding that allowed him to write a whole book on his ignorance. It’s a bit like Nicholas Wade’s book, A Troublesome Inheritance — another instance of Dunning-Krueger fused with 19th century racism.

Hey, though, if you care about this stuff, and are interested in how good science can be communicated well, I have a treat for you: tomorrow, Tuesday, at 6:30 Eastern, you can tune in to an online discussion between Jennifer Raff and Carl Zimmer on Why You’re You: Explaining Heredity to a Confused Public.

Heredity, genetics and #SciComm, let's talk about it! Featuring @carlzimmer (who has a new book!) @JenniferRaff and @leHotz. Join us TOMORROW (10/9) at 6 p.m. at @nyu_journalism or online at 6:30 at https://t.co/dqGjQIOTRX and tweet your questions with the #kavliconvo hashtag! pic.twitter.com/5d9w937cet

— Dan Fagin (@danfagin) October 8, 2018

Note that this is not a debate — it’s a conversation between two well-informed individuals on good science, and how to explain it. I’ll be checking in!

Just another mundane spider update. This batch of babies are now 18 days post-fertilization, and they’re just rockin’ out in their dish.

I also got some good news: I was awarded a small in-house grant to pick up a bunch of supplies for embryo imaging, so that’s in the works. I ordered a few necessities today.

And now everywhere I go on the internet, ads for halocarbon oil pop up everywhere. Or does everyone get those?

Everyone has been telling me about this time-lapse video from the Nikon Small World competition. I twitch a bit when I see it. It’s just too familiar, because I used to work on those cells.

Just to orient everyone, that’s an embryonic zebrafish, head to the right, tail to the left, lying sort of upside down with a 3/4 twist, so you’re looking down on the dorsal side and also seeing the left flank of the animal. Does that help?

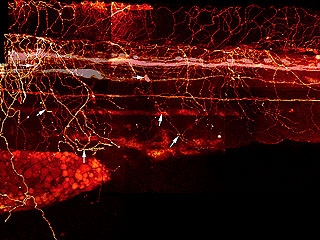

As you watch it, you’ll initially see two parallel rows of cells located in the dorsal spinal cord — those are called Rohon-Beard cells, and what they’re going to do is a couple of things. They build a longitudinal pathway within the spinal cord so you’ll see they’re all connected by a bright line of labeled nerves running through the spinal cord, from tail tip to hindbrain. They also start sending out peripheral growth cones, building a network of fine axons that cover the animal just beneath the skin. These mediate tactile sensation in the fish.

About a third of the way through, another pathway will become obvious: it’s the lateral line nerve, which starts growing out of a primordium just behind the ear and makes a bright pathway along, in this case, the left side of the fish. I presume there’s another one on the opposite side that we just can’t see.

What makes me twitch is that years ago, I tried to figure out how the Rohon-Beard cells make that meshwork. I had a Ph.D. student, Beth Sipple, who collected a lot of data the hard way, by labeling one or a few cells at a time, fixing them, and then trying to reconstruct the interactions from these single cell, single time-point observations to get an idea of how the growth cones were crossing over each other. She also injected dye into that longitudinal pathway to fill a subset of the Rohon-Beard cells and see how their peripheral arbors were organized, as in this image from her thesis.

DiI Labeling of Rohon-Beard and Dorsal Root Ganglia Processes in a 3 d Embryo

Rohon-Beard and DRG processes were labeled by injecting DiI into the DLF and back-filling cell bodies and processes. * indicate the Rohon-Beard dorsal fin processes. Long arrows indicate position of Rohon-Beard cell bodies. Short arrows indicate the position of DRG peripheral processes

It would have been so much easier if we’d been able to just label the whole mess and watch them develop. There’s as much information in this video as there was in hundreds of samples made the old-fashioned way.

This is how we framed it, a few decades ago.

If one looks at the network of Rohon Beard cell sensory arbors once they are well established, the pattern of innervation is quite dense and complex. It is almost as if someone laid a series of irregular nets, one on top of another in random fashion, over the surface of the skin. There appears to be no regular morphological pattern to the arbors individually or as a whole. This is unlike the situation seen in the Comb cell projections of the leech (J. Jellies) which have a distinct shape and a well distributed outgrowth pattern. So how does a Rohon Beard cell arbor (or any developing sensory arbor for that matter) ‘know’ how to grow and branch its dendrites optimally in order to cover an entire receptive field (the skin)? An optimal pattern would arborize over a region such that:

- no point in the field is further than a given distance from a neurite

- no point in the field is excessively innervated

- all regions are equally densely innervated

In other words, each arbor should have a few holes and no clumping regions, as is seen in this image of a Rohon Beard cell arbor at about 23hpf below:

The question I was interested in was how to form a distributed network, with minimal clumping or gaps, and I measured all kinds of lengths and angles and rates and densities to try and figure out how it assembled itself. We inferred a couple of things: that individual axons avoided fasciculating with each other, but that there was no aversion to crossing over each other, and we also inferred that the growth cones had a weak preference for regions of the skin that were not already innervated.

I’m looking at the video and saying, “we were right”, but still wanting to get in there and measure branch angles and trajectories. And also, “oh, man, this technology would have made everything so much simpler.”

I really was considering going to the Nuttings’ creationist seminar in Minneapolis this week, but I decided not to. I’m sure it will be totally pants, but then I discovered that a student, Elliott Jungers, will be presenting his senior seminar in Science 1020 at 5pm today on “Pax6 mutation in the model organism Astyanax mexicanus“, and a colleague in geology, Keith Brugger, will be presenting a faculty seminar in HFA at 5pm Thursday, titled “Small Science to Global Climate Models: or Why Anyone Would be Interested in Colorado’s Weather 20,000 Years Ago”. All are open to the public.

Why should I drive 3 hours to hear garbage people lie and talk garbage science when I can stay right here and listen to good stuff? In fact, I bet there are better talks going on at the Twin Cities campus all of the days that the Nuttings are babbling.

It’s October. That means I’ve got free rein to post horrifying spider videos, right?

I’ve got a feeding schedule for my colony, so every Monday and Thursday I open up the incubator and fling a bunch of living, walking, wingless Drosophila into every spider tube.

Today is Monday.

Now usually, the spiders sit unperturbed by the intrusion of insects into their domain, and they’ll just watch and wait, and the next day I find the withered corpses of their prey in their webs. Today, I guess Betty was hungry, because she leapt unto one of the hapless flies within seconds of it landing on the web. She was so fast she had it trussed like a Christmas turkey before I could get her under a camera.

I got a bit of the aftermath in a video, at least. It’s below the fold. It’s probably not a good one for the arachnophobes to watch.

Now you’ll understand why I regurgitated that awful Simmons debate: because I made a video about precisely the phenomenon he claims never happened.

I’ve got these spider babies that I now know are exactly 8 days old after they were laid in their mamma’s egg sac, and we’re seeing the transition from spherical egg to lightly sculpted leggy thing wrapped around a spherical ball. So I took some pictures. I also tried putting them on my compound scope and seeing if I could visualize cells in the tissue — it didn’t work. The spider embryos are thick and round and opaque, and further, I was just looking at them dry — I’ve got to work on getting them in a better medium and improving the optics.

Also, the more bloodthirsty of my followers have asked me to catch the babies in the act of feeding, so just to appease them (please don’t hurt me!), I’ve also included a short clip of what happens when I dump a bunch of flies into a tube of baby spiders.

Sea lions really are the bad guys.