Finally, one quack goes down. The notorious anti-vaxxer Sherri Tenpenny has had her medical license suspended, at long last. It should have been done long ago.

Two years ago, a Cleveland area physician strode into the House Health Committee room and told state lawmakers that COVID-19 vaccines magnetize their hosts and “interface” with cell towers.

Her comments, the subject of widespread ridicule, triggered a swarm of 350 complaints to the State Medical Board and a chain of events that led to the regulators indefinitely suspending the medical license Wednesday of anti-vaccine activist Sherri Tenpenny.

Oh, yeah, the magnetized people claim. It’s as stupid as it sounds.

It was June 2021, just as scarcity of COVID-19 vaccines began to wane and health officials focused on the yeoman’s work of convincing hundreds of millions of Americans to take up the novel products. However, many conservatives sought to undercut this campaign, often under arguments about “medical freedom.” Tenpenny, speaking before a crowd of anti-vaccine activists, warned of purported dangers of vaccines with a firehose of debunked and misleading statements.

“I’m sure you’ve seen the pictures all over the internet of people who have had these shots and now they’re magnetized,” Tenpenny said to the panel of lawmakers.

“They can put a key on their forehead and it sticks … There have been people who have long suspected there’s an interface, yet to be defined, an interface between what’s being injected in these shots and all of the 5G towers.”

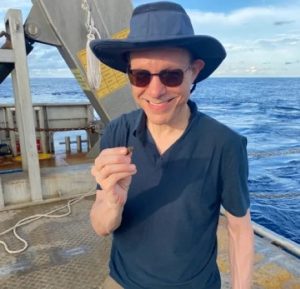

Although…it’s true. I’ve received many vaccinations, and I just tested it, and look, I can make pennies stick to my forehead! I’ve been able to do this for my whole life, though, and I can’t say it’s particularly useful. I guess I could entertain my granddaughter for a minute and a half with that trick. Or drive an anti-vaxxer into a frothing fury for a couple of years.

Unfortunately, stripping Tenpenny of her medical license won’t slow her down in the slightest. It’s not as if she’s been practicing medicine all this time, she instead peddles “alternative” treatments to the gullible. Being denied a license by The Establishment will probably enhance her reputation among her clientele.

Her podcast is still squawking lies into the æther, and she has the ear of influential people — such as Joseph Ladapo, the surgeon general of Florida.

Florida Surgeon General Joseph Ladapo recently appeared on the podcast of a prominent anti-vaccine advocate, where he continued to make claims about vaccines that are contradictory to widespread medical consensus.

Medical experts have said Ladapo’s claims are dangerous, and that his very presence on the podcast — and other recent appearances on shows promoting falsehoods and conspiracy theories — gives credibility and support to anti-vaccine rhetoric.

Lapado’s latest comments are part of a litany of dubious claims that have alarmed public health officials in Florida and across the country since he got appointed surgeon general more than a year ago by Gov. Ron DeSantis.

This is a guy who says the risks of the COVID vaccines outweigh the benefits for most people, who has blocked the use of COVID vaccines in Florida, and refuses to use a mask — but he is a Harvard graduate, you know. He’s also blatantly ideological and conservative, making his comments to Tenpenny particularly ironic.

Despite being the head of Florida’s Department of Health, Ladapo bashed a majority of the nation’s physicians for their vaccine beliefs, saying they cannot separate themselves from their ideologies and politics.

“Our colleagues, for the most part, can’t be brought back into alignment with reality,” Ladapo said on the podcast. “I don’t have any faith that most of our physician colleagues, sadly, can be rehabilitated.”

Tenpenny went so far as to compare current doctors with those in Nazi Germany who participated in or didn’t oppose the mass killing of and experimentation on people, namely Jews, citing a passage written into the first page of the foreword of Ladapo’s own book, which he promoted on the podcast.

Kudos on getting a license suspended after years of talking, but Tenpenny isn’t going to hesitate and is going to continue to poison the discourse for many more years to come — and she’ll make bank off it, too.