I’ve complained before about music theory, and how it fails to actually address any of the music I actually like. One kind of music I have in mind is drone music. Consider, for instance, this reddit thread on the music theory of SUNN O)))

Honestly most drone is fifths and minor scales, it’s not really complicated.

The attitude being expressed is that drone music is too simple to require any music theory. This is a failure to engage with the music on its own terms. If that’s all there is, then what, pray tell, distinguishes different songs and artists? Are they just all interchangeable?

While it may be the case that drone music is particularly simple, I feel that this only makes the lack of a music theory all the more frustrating. Most music theory is frankly too complicated for me to understand, and it would actually be nice to have some simple music theory for once, if only music theorists didn’t think it was beneath them. In any case, I think the theory behind drone music is likely more complicated than they are making it out to be. Drone is highly preoccupied with texture (aka timbre)–a subject so difficult that music theory as a field has basically given up on it.

Anyway, in the spirit of being the change I want to see, I analyzed the spectrograms of a couple SUNN O))) songs.

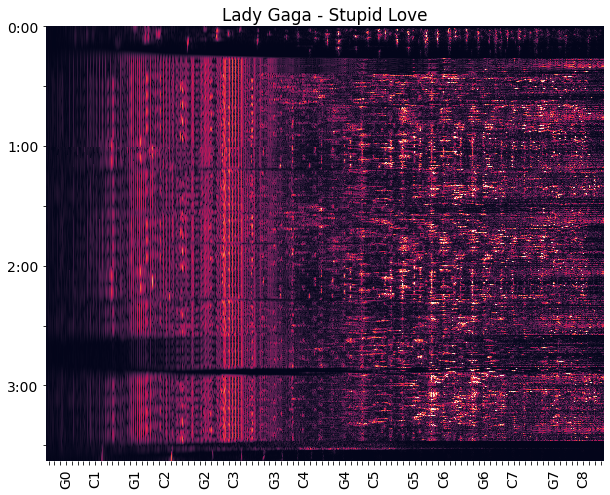

But before I get to SUNN O))), I feel like I should maybe establish what a spectrogram is, especially for people who have never seen one. Here’s a spectrogram of a pop song.

Lady Gaga – Stupid Love. No mockery is implied in this choice, Lady Gaga is fine. I made these spectrograms in Python, but if you look around the internet there are easier ways to produce spectrograms, accessible to anyone.

The vertical axis shows time, the horizontal axis shows frequency. Brighter colors represent larger volume. The frequencies are labeled with letters and numbers, where the letter represents the note and the number represents the octave. So C2 is one octave above C1, C3 is one octave above C2, and so on. The frequency tick marks represent all notes in standard tuning, so the first tick after C is C#/Db, the second tick is D, the third tick is D#/Eb, and so on.

The first thing that might jump out about the spectrogram, are the vertical bars in the G1 to C3 range. I believe this represents the song’s thumping bass. You might also notice a gap in the bass around 2:30 to 3:00–this is the song’s bridge.

Of course, when you actually listen to the song, what stands out the most is the singer’s voice. I think the voice is somewhere in the C6 region, but I can’t really distinguish it in the spectrogram. There are just so many other things going on in this song (typical in popular music), and it doesn’t help that we’re basically cramming three and a half minutes of information into small image.

You should have two takeaways from this image: Spectrographic analysis is limited in what it can do. And what stands out in the spectrogram is not necessarily the same as what stands out when you listen to the music.

Let’s move on to SUNN O))).

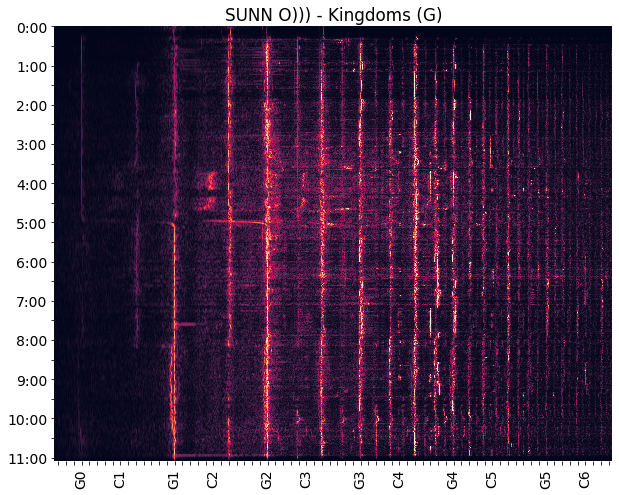

The difference is stark. Despite 11 minutes of information being crammed into a small space, the texture is so lucid that you can tell exactly what notes are being played. And at first glance, it’s basically the same notes for the entire song.

I know people joke about drone music being all about sustaining one giant chord for ten minutes straight, but this is not literally true for most drone music, or even most SUNN O))) music. It is, however, the literally true of Kingdoms (G) (as well as the other tracks in the same album). This makes Kingdoms (G) a good subject for study, and unusually amenable to spectrographic analysis.

Since it’s mostly just one chord, what is that chord? As the title suggests, it is a G chord. Each vertical bar represents one of the harmonics of G—that is, all the integer multiples of the G frequency. The fundamental note is the faint vertical bar at G0. The first bright bar is G1, which is twice the frequency of G0. And then D2, which is three times the frequency. G2 is four times the frequency and so on. At higher frequencies, the bars get closer and closer together, because the plot is on a log scale.

Harmonics, by the way, are not unusual. Almost everything we think of as a single note actually contains many harmonics, and those harmonics contain the information that allow us to identify the instrument. What’s unusual here is that the harmonics are so discernible, even up to very large numbers.

One thing about harmonics, is that they do not line up with the standard tuning system. For example, the fifth harmonic is close to B3, but is slightly flatter, by about 13 cents (ie it’s 13% of the way from B to B flat). And by the way, I checked the precise frequency of this note, and I found that it is about 13 cents flat. You could point to the B3 and say this is a G major chord, but I think it’s better to just describe it as G plus all its harmonics. (Guitarists would call it a G power chord.)

When I listen to the song, what stands out from moment to moment are the high notes played on top of the G chord. Most of these high notes are simply strengthening some of the harmonics of G. For example, around 3:00 to 3:30, I hear (and see in the spectrogram) a bit of the 21st harmonic, which is otherwise very quiet. The 21st harmonic lies at C5 (perfect 4th), but is 30 cents flat. That’s right, SUNN O))) is microtonal!

There are also many notes that don’t line up with the harmonics, which provide a source of dissonance and tension. For instance, there’s a noticeable streak near C2 (perfect 4th) at the 4:00 mark Also at the same time there’s a note at E4 (major 6th). Together these imply a second-inversion IV major chord. Does this mean that it’s not actually one single chord played for the entire ten minutes? Perhaps.

There are many other things I could point out in the spectrogram, but let’s take a look at another SUNN O))) song.

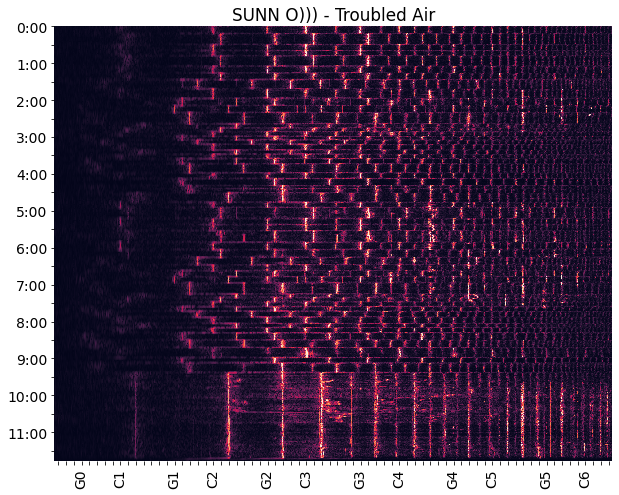

Troubled Air is a more typical SUNN O))) song, in that it has lots of chord changes. Well, it changes chords 4-8 times a minute. As explained in an Adam Neely video, the slowest beat that humans can experience as “rhythm” is about 33 beats per minute. This song is slower than that, so we could say that it basically doesn’t have any rhythm as far as the listener is concerned.

Much like the previous song, I would describe each chord as being one fundamental note along with all its harmonics. Here’s a transcription of each fundamental note:

0:00 – 1:00 C, Db, C, Db

1:00 – 2:00 C, Db, Bb, C

2:00 – 3:00 Ab, G, A, Eb, Db, C

3:00 – 4:00 Ab, Bb, C, Eb, C, Ab, A

4:00 – 5:00 C, Ab, A, D, C

5:00 – 6:00 Db, C, Db, C

6:00 – 7:00 Db, Bb, C, Ab, G

7:00 – 8:00 A, Eb, Db, C, Ab, Bb, C

8:00 – 9:00 Eb, C, Ab, A, C

9:00 – end Ab, A, D

I’m not going to analyze all that, although I observe that it’s all in the Phrygian mode of C, with the notable exception of the A chords and the final D chord.

When I listen to the music, one thing that particularly stands out within the first 20 seconds is the E5, which sustains through the C to Db chord transition. This is the 20th harmonic of C, and the 19th harmonic of Db. In the C chord, it is a major third, and in the Db chord it is a minor third, allowing us to interpret these chords as C major and Db minor.

Now the odd thing about this is that the minor third is usually thought of as an approximation of the ratio 6/5, but in this case it’s a 19/16 ratio. Is 6/5 equal to 19/16 now? It is, if we set 96/95=1. In music theory, if we have a ratio that’s very close to 1, we call it a “comma”. When we tune our notes to ignore a comma (setting it to 1), we say that we have tempered out the comma. When we have a chord progression that implies a comma, it’s called a comma pump. So, with just two chords, we’ve heard a 96/95 comma pump. Fun.

There’s a lot more to say about these two songs, about SUNN O)))’s larger body of work, as well as the work of other drone artists. But I think this analysis suffices to show that there are things to understand and talk about in drone music, despite its simplicity. Understanding the theory of drone is not a requirement to either produce or appreciate the music–obviously not since at this point nobody understands the theory of drone. But I feel that a bit of theoretical discussion couldn’t hurt.

“The attitude being expressed is that drone music is too simple to require any music theory. This is a failure to engage with the music on its own terms. If that’s all there is, then what, pray tell, distinguishes different songs and artists? Are they just all interchangeable?”

One of the biggest issues I’ve found is that soooo many people equate “music theory” with “harmonic analysis”, and even then usually only through the perspective of Classical European harmony from the 17th-19th centuries, which is an incredibly narrow view of the whole thing. Part of it is of course that music used to only be recorded by using notation, but we’ve had recorded audio music for over century now, not to mention that staff notation itself is a relatively recent invention. A lot of the things that you address here are things that audio engineers and producers are more concerned with, but it isn’t usually thought of as “theory”, even though it’s dealing with music at its most basic form.

“There’s a lot more to say about these two songs, about SUNN O)))’s larger body of work, as well as the work of other drone artists. But I think this analysis suffices to show that there are things to understand and talk about in drone music, despite its simplicity.”

The focus of drone music, based off your analysis, seems to be about timbre, which is created by all of these harmonics. Applying the lens of Classical European music to it is silly, because while there was some focus on that at the time when it comes to orchestration, that /also/ isn’t every really considered “music theory”. Not to mention its generally not spoken about in such a mathematical way.

Spectographs are a really interesting way to look at this too. Again, I really only ever saw them in our audio production textbooks, but even then they weren’t really used to look at a whole song, just showing off the timbre of different instruments and explaining the basics of harmonics. DAWS will sometimes use spectographs as visual aids, but again its more moment-to-moment, instead of showing the piece as a whole.

I took (most of) an online music theory course to try to understand why I’ve been missing all these years, and it was pretty quick with the disclaimer that it dealt with classical music theory in Western scales and was in no way exhaustive of music. I’m not going to say music theory is not complicated, but I feel it would be a lot simpler for me to grasp without the stumbling block of arbitrary and archaic notation for things that can be expressed uniformly and mathematically.

I don’t know enough about drone music to say, but it sounds at least as “serious” as Steve Reich’s tape loops. The interesting question is how does your brain respond to sound, and why is it (hopefully) a satisfying experience for one reason or another? This is broad enough to encompass many kinds of analysis. (And to be honest, I am not a huge fan of Steve Reich, but some of it works as a kind of meditation if not a really enjoyable listening experience.)

If I’m not mistaken (pardon my weasel words), Leon Theremin took special pride in the pure sine waves produced by his instrument. These seem trivial to produce now but I guess they had to wait for electronics.

@assignedgothatbirth #1

Yep, I agree. I don’t like how music theory confines itself to a particular kind of analysis, and declares the music it cannot analyze as uninteresting.

Yeah, something that motivates me to look at this is dabbling in electronic music production. I don’t really have a method (or the skill) to just jam on an instrument, so I actually need to think about what is happening.

@PaulBC #2,

I took music theory in high school, and have otherwise learned it from the internet. So my knowledge is spotty in some places and augmented in others.

I’m not familar with Steve Reich’s tape loops, but Reich is at least in the same general area as drone. The one drone composer that I’ve seen get attention from the academy is Phill Niblock.

@4 See, e.g. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/It%27s_Gonna_Rain

Time normally goes left to right on spectrograms. It’s a little disorienting, but I can just tilt my head to the right I guess.

The frustration is understandable, but you don’t expect much from a reddit thread, right? (That applies to most things on the internet, unfortunately.)

The literature has had lots to say about various forms of minimalism, ambient electronic music, and so forth. I don’t know, maybe what people call “drone music” hasn’t gotten enough attention of its own…. What I’ve heard is pretty simple in many respects, as you also noted. I just don’t know what there may be to say which hasn’t already been said. (That is, beyond coming up with a more comprehensive theory of timbre, which is a ridiculously big/complicated project. But once we understand our brains a little better, maybe decades from now, we’ll be more prepared to tackle that in more detail. It’s still not going to be pretty or easily comprehensible.)

As an aside, there’s never been a really satisfactory way to classify works into genres, as many listeners of popular music are inclined to do. It’s kind of a tricky or tendentious question to ask what a “genre” even is in the first place. With regard to musical features (not extra-musical stuff like the singer’s haircut, political affiliation, etc.), many simply do not know where to begin; and some seem almost insulted or threatened by the fact that there’s anything to learn about music. That doesn’t stop them of course. It’s as if there were billions of amateur taxonomists running around, and the people who actually know more than just a handful of things about biology are expected to validate whatever folk theories they might concoct. It’s pretty frustrating, and it never ends. Sorry, no real point in complaining here, and I don’t know why I bother….

Anyway, the fact is, we don’t have a giant industry to play with in musicology, like you’re familiar with in the physics world or in the other sciences. There aren’t that many people involved, resources are extremely limited, and they can only spend so much time studying topics that are the most interesting or important for them. I’d like it to be different, but that’s how it is. I mean, if somebody feels like donating a billion dollars to music departments around the globe, I’m sure they’d very quickly find a use for it and make a lot more progress.

But there’s really a huge amount of ground to cover. Music has existed in some form since prehistoric times, at any given time it’s being made by countless people all over the world, and you can look at it from a bunch of different angles. You can try to understand it in historical or sociological terms. A lot more attention has shifted in the past few decades to recent developments in the cognitive sciences, to better understand it an individual level. Philosophers have made some important contributions every now and then. And of course it’s always involved math and physics at some level. That’s sort of nice in some ways – I like that it’s not a very narrow topic and all kinds of stuff is interesting about it – but that’s also what makes studying it extremely challenging.

Well, that seems like stretching the meaning of the term as it’s normally used. It’s just a naturally occurring harmonic, and except for octaves those are never the 12 EDO notes (not exactly). So, you’d find the same in all sorts of music that is not regarded as microtonal, like Beethoven and Mahler and whatnot.

The idea kind of breaks down when we’re talking about timbre – when we hear for example a single unified voice/instrument, performing “one note” that has certain characteristic properties, qualities, colors – and not really talking about the harmonic/melodic relationships of multiple pitches which at least seem to come from different sources and can be differentiated in that way. The latter is more or less when it’s useful to distinguish between music that is or isn’t microtonal, because the former covers nearly everything.

PaulBC:

Well, you need to read and understand it, but we do use tons of things other than notation. There are graphics of all kinds (charts, graphs, diagrams, etc.), and of course, notation itself is just a sort of heavily stylized graph of frequencies over time. Numbers and the like are also heavily used, to represent all kinds of things in different contexts.

But no notation? That’s not happening. It’s sort of a lingua franca for musicians, which we all learned anyway before we’re ready to go deep diving into the theoretical waters. It’s not always the best option, certainly, but it can be very convenient. For me it’s about like reading and writing English, because I can immediately understand what I’m seeing, and I know other musicians are in the same boat, so we can use that to communicate with one another.

consciousness razor@7 I’m not expecting it to change. However, there are a lot of things that make a lot more sense to me if I translate them into equivalent math, e.g. modular arithmetic. I was quite excited (though it’s trivial) when in my late 40s I finally understood why the black keys were placed the way they are (and that was only because I was helping my kids with piano lessons and finally got curious). But this, again, is something that is simple to understand in terms of arithmetic mod 12 but is usually presented with additional complication (circle of fifths, etc.) in traditional music theory.

If I were writing a brief note about music to my younger self, I would summarize: the octave doubles the frequency, you go up evenly by the twelfth root of 2 on each step (at least the way pianos are usually tuned). A few of the places in between are very close to small integer fractions: 3/2, 4/3, and we give them names (and there are some other reasons why we hear these harmonics as sounding nice). Actually, I did know that frequencies went up by 2^(1/12) and had used that to generate musical scales on an ancient microcomputer, but I had no idea what fifths were or why they were called that. (And for whatever reason my K-12 education omitted music theory or any music instruction, which is a shame. I might have even liked it, but by the time I got to college I felt intimidated by the whole thing.)

This isn’t fresh in my mind anymore, but I remember struggling to enumerate all possible four-note chords the way it was explained and finding it significantly easier with integer notation (which I started to reconstruct by myself and then looked up).

I don’t dispute the need for having some notation. I’m not persuaded that the notation used by musicians is even close to good notation, let alone the best. However, I also get that they need a lingua franca, obviously it works and people learn it, and given the sheer mass of human beings involved, it’s not likely to change.

My point (if any) is that some of the initial terminology makes it unnecessarily mysterious. Once you get to a certain point in any notational system, the learning curve probably doesn’t matter all that much.

To be a little more clear, I actually do get why its useful to have names like diminished, half-diminished, minor, minor major, dominant, major, augmented major for chords instead of tuples of numbers, since these carry meaning and history.

But maybe owing to my own peculiarities, I found it much easier to write out a table of all possible chords with 3 or 4 half steps between notes and then learn the names for them than to go the other direction, which seemed to be the way it was taught (in this one particular course, which is all I have to go by).

I’m pretty good with musical notation, so I don’t have an issue with it. I think it’s actually an advantage that archaic notation is somewhat resistant to change, because otherwise you would have a hundred proposed notations that nobody would agree upon. The difficulty is when archaic notation fails to capture certain possibilities (as occurs when you go beyond 12TET).

@CR #6,

You’re thinking of “microtonal” as a class that contains some kinds of music and not other kinds of music. And while that’s a useful concept I think there’s also some value in thinking of microtonality as a dimension of analysis that can be applied to any music.

In any case, I do think that SUNN O))) belongs in some sort of class of microtonal music, because to my understanding these are not just naturally occurring harmonics, they’re naturally occurring harmonics that have been amplified through some sort of deliberate feedback loop.

I studied ALL the (Western) music theory, taking the equivalent of SEVEN different classes studying it between the ages of 12-17 (theory, harmony and counterpoint classes for which I wrote exams with the Canadian Royal Conservatory of Music…I also studied music history…which I loathed…and piano – I passed my Grade 10 exam* with Honours! – with the Conservatory). This included information on everything from Renaissance and Baroque music to a small amount of late Romantic and early Impressionist music (not a focus, but at least it was there). Most of it was Baroque and Classical though. And as I was also stumbling my way into learning how to WRITE music at the time, the theory I learned definitely informed my compositions (for example, fugues – I tried and tried to write fugues, and only successfully completed 2 of them over a period of 4-5 years, both 3-voice fugues…I tried to go 4-voice, but my brain just couldn’t handle that extra voice). Which is why I REALLY wish they’d gone beyond Western music in those courses; there’s a whole world of music out there, and it would’ve been nice to be exposed to the theory of at least a few other cultures. I would have definitely written better music – as it stands, the best music I wrote were those pieces that took some crazy idea I worked out in my head during some boring school/university class and applied some of the theoretical constructs I had learned to it (breaking a few rules along the way of course). A wider theoretical base would have given me many more opportunities. Oh well.

Anyway, youtuber and bassist extraordinaire Adam Neely discusses this very issue (the extremely narrow focus of music theory education in the West, particularly the US) in his most recent video: Music Theory and White Supremacy (original title: Music Theory is Racist – I really think he should’ve stuck with that title, clickbait-y though it is, but whatever). Check it out – it’s REALLY interesting: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kr3quGh7pJA

*Grade 10 is the highest grade. However, you could go one step further and take the ARCT – Associate of the Royal Conservatory of Music – exam (which is effectively grade 11, thought they don’t call it that – it qualifies you to be a teacher registered with the Conservatory). Unfortunately, I was ineligible as they require a passing grade on every SECTION of the Grade 10 exam to progress, and I just suck at sight reading. REALLY SUCK. So I failed that part of the exam, and failed again in a supplemental, a year later. Incidentally, I also failed the technique portion (scales, arpeggios, etc.) the first time as well, but passed THAT supplemental (it turns out that a ludicrous amount of practising can improve my technique…but NOT my sight reading). And as they allow you just one supplemental before requiring you to re-take the whole Grade 10 exam if you want to progress, I decided all that work wasn’t worth it (especially since I wasn’t convinced I should even TRY to pass an ARCT, if the option was available to me). It took me a whole year to prepare the first time, practising an average of 15 hours a week.

@VolcanoMan #11,

I really like Adam Neely’s video. It was in my link roundup a few days ago. I was thinking about that when I wrote this, because I was trying to envision a music theory that isn’t bound to the harmonic practices of 18th century European composers. I’m still pretty grounded in western traditions here, but at least these are newer western traditions.

(Also, for context, I’m also really into xenharmonic music. That’s why I’m pretty keen to spot microtonality, and where I learned about comma pumps.)

Sure, I get it. And I realize this is something I’ve known since I was very young, so I’m not the person to ask about difficulties in learning it later on. Much of the introductory material that’s taught to music students is about getting them accustomed to European music from around 1750-1850 for the most part, so lots of the strangest and most obscure aspects of tonality and so forth are give much more prominence than they ought to have. Your confusion and frustration is a result of those pedagogical choices.

Obviously, that isn’t about learning music in general. So you eventually have to unlearn some of it or at least understand those things in a different way, as a tiny part of a much bigger musical world. I would be happy if elementary music teachers took a different approach, but on the other hand, this is the kind of thing many are interested in learning about right away (especially younger kids), so it’s kind of tough to deny them that.

We do something kind of similar in math, for example. You first learn some very basic stuff about arithmetic and such, because those things will be useful to you in life and will be needed for a lot of other subjects you’re about to learn. More advanced ideas, many of the proofs required to put all of it on a solid foundation, the history, etc., are not usually covered until much later. The big difference is of course that basically everyone gets at least a dozen years of pretty solid math classes in a highly-structured curriculum, while the general music “appreciation” classes (not band/choir) that some may take don’t even begin to scratch the surface, if they are even taken, because they’re typically considered optional.

I remember talking to my dad about it: back in his day, growing up on a farm in a rural school district, there was simply nothing at all related to music. Honestly, it’s hard to say what they actually did teach, because it sounds like almost nothing compared to what I went through, but he came out smart anyway.

Another thing to keep in mind is that our notation system was developed for performers (and to make things relatively easy for the composers who write for them). People who are analyzing a piece of music or coming up with a theories about music are at best an afterthought. (Earlier forms of notation were also much more vague about tons of stuff, but some improvements were very gradually introduced over the centuries.) I still maintain what I said about it being useful, but that’s not to say it’s unproblematic.

So, it’s “for performers” in some sense….. But do you wonder why treble clefs or bass clefs look like that, for example? Don’t. Just don’t. Those are elaborate ways of marking the G and F lines, respectively, and they’re doing that because … well, it’s a very long and convoluted bit of history that you probably don’t care about. And you didn’t actually need it, because that’s probably not how you learned to identify the notes on the staff, but like it or not you’re getting that information anyway.

The thing is, that is the type of thing you should unlearn, because it presumes there are “chords” which are triadic (spaced apart by 3 or 4 semitones), and it’ll end up giving you something that fits pretty well into the framework of tonal music. Outside of that, though, what good is it?

Assuming twelve notes per octave, as we do, there are 116 possible tetrachords. Those are sets with four elements (including multisets, and not treating inversions as equivalent because we do hear a difference between “up” and “down”). If you leave out multisets, meaning that all four elements need to be distinct pitch classes, then there are just 43. So 73 multisets and 43 “regular” ones, for a total of 116.

Most of them don’t have names, like “dominant seventh” or “half-diminished seventh,” and those names won’t help you understand much anyway. Just use the numbers 0 through 11 (modulo 12) and you’ll be fine. But actually, you can do better than a table with a bunch of numbers: they can all be mapped (or put into a configuration space, to borrow a physics term). The topology is kind of weird, but it isn’t really too hard to grok in the case of four notes.

There are also 43 regular octochords with eight distinct pitch classes, because they are complements of the tetrachords — the “gaps” between notes in a tetrachord are the same as the “notes” of some complementary octochord. Again, that is excluding cases where there are multiple notes with the same pitch class. There are many more eight note multisets (thousands of them), but in practice those may not be useful to consider when analyzing most pieces of music, so you may not need to worry much about such things.

The general pattern for what I’m calling “regular” sets is not too hard to remember, and it’s nicely symmetrical. (However, the number of multisets just keep growing as the sets increase in size.) Without going through any proofs here, I’ll enumerate the results:

0 and 12 notes: 1

1 and 11 notes: 1

2 and 10 notes: 6

3 and 9 notes: 19

4 and 8 notes: 43

5 and 7 notes: 66

6 notes: 80

Note that what I’ve been lazily calling a “set” is really a set class. If you rotate these shapes around in pitch class space, that’s just a transposition (in music theory terms). Those are considered equivalent, because they’re the same shape which is just rotated, so they go into the same class. And we’re not worried about the order of the elements in a set (whether that’s a temporal order, going from low to high, or whatever kind of ordering you like) — there are a bunch of permutations of each, which again all go into the same bucket. Because we can. And do note that we’re building these with pitch classes, not pitches in a specific octave.

So out of the vast number of possibilities, we can simplify the picture a huge amount by classifying things in this way. Importantly, it’s just using the structures themselves to do the job, not imposing any other restrictions that depend on the preferences of Europeans in the 18th or 19th centuries. Then, if you want to, you can go back to looking at classical music or whatever, to try to see how it fits into the bigger picture.

My goal was less to really get a deep understanding of music (at 55 I think I may have missed that boat long ago) than at least to have a rough understanding of what people are talking about when they discuss Western tonal music the usual way and not feel like a complete idiot. I’m going to confess that I’m still not sure I can actually hear if something is played in a minor or major key, though I at least know what these are. I thought it was also kind of interesting to learn about switching between keys by changing one note in a chord (it reminded me of something… maybe a Gray code would be a good analogy). Most of the rest (this was introductory) was about the names of different chord progressions.

I think your explanation makes more sense than the typical one, but this is sort of what I was getting at. There is a uniform structure that gets obscured by all the names. If you learn early enough, it probably doesn’t make a difference.

Heh. How long has it been since your last confession?

If it’s any consolation, there’s plenty of great music which is neither or which is ambiguous (sometimes that’s deliberate). And even if something is unambiguously in a major key, let’s say, then there are still minor or minor-flavored chords in it most of the time, so hearing them may be confusing for you too. Also, the chords (037) and (047) are inversions of one another — flipped upside down, or going the opposite direction around the pitch class circle if you like. Also, major and minor (meaning keys or scales) are just modes of the same diatonic scale but with a different starting point.

So, you have a bunch of pretty reasonable excuses.

Identifying notes and chords by ear is hard. That’s why I made spectrograms instead. A while ago I had a project to identify chords using machine learning. Turns out it’s hard even for a computer.

It definitely takes a lot of practice. I was trained specifically to do it, and it’s part of the job, meaning I get to exercise those muscles regularly. So there is that. But honestly I still don’t really get how I do it … it just happens. It’s like identifying the color purple when I see purple. No big deal.

But if really complicated things are happening in the music, that’s not so easy, in the same sort of way that a complicated image can be hard to take in all at once. (Do I remember seeing green there, or was it blobs of yellow and blue next to each other, or what was that?) It can also be tricky to sight-read something and sing all of the pitches (accurately), particularly if the line has a bunch of unusual intervals one after another. If I had to do that more often, then maybe it wouldn’t be so tough either.

I like that analogy. I wonder if very young kids were taught intervals with the same frequency and routine nature they are taught color blending, if that would be the normal situation and no one would find it remotely mysterious (unless they really could not distinguish notes).

As for me. I don’t think I’m tone deaf, though I played around with a phone app long enough to conclude that I don’t have absolute pitch (could I develop it? no idea). I think I have a good memory for melodies, but it is hard to persuade anyone else of what goes on in my head. I found “Bad Singer” by Tim Falconer really interesting. https://www.amazon.com/Bad-Singer-Surprising-Science-Deafness-ebook/dp/B019G1R0V0