Well, actually, Yoshinori Ohsumi has won the prize for his work on autophagy, a cellular process you may have never heard of before. The word means “self eating”, and it’s an important pathway that takes chunks of the internal content of the cell and throws them into the cell’s incinerator, the lysosome, where enzymes and reactive chemicals shred them down into their constituent amino acids and other organic compounds for reuse. What makes it interesting is that the cell doesn’t want to just indiscriminately trash internal components; there are proteins that recognize damaged organelles and malfunctioning bits and packages them up in a tidy little double membrane bound vesicle that fuses with the lysosome and destroys them.

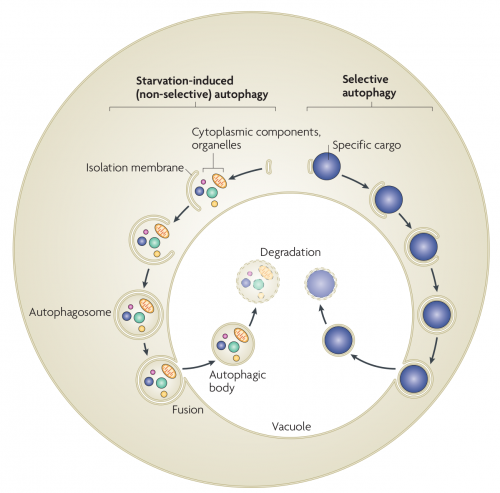

At least, most of the time it’s selective. It was first characterized by Ohsumi in yeast, where, if you starve the cells, they start self-cannibalizing to survive. If you use mutant yeast that lack some of the degradative enzymes, they are unable to break down the materials being dumped into the lysosome, and the vacuoles just get larger and larger, making it relatively easy to screen for changes in the machinery for autophagy.

Autophagy in yeast. In starvation-induced (non-selective) autophagy, the isolation membrane mainly non-selectively engulfs cytosolic constituents and organelles to form the autophagosome. The inner membrane-bound structure of the autophagosome (the autophagic body) is released into the vacuolar lumen following fusion of the outer membrane with the vacuolar membrane, and is disintegrated to allow degradation of the contents by resident hydrolyases. In selective autophagy, specific cargoes (protein complexes or organelles) are enwrapped by membrane vesicles that are similar to autophagosomes, and are delivered to the vacuole for degradation. Although the Cvt (cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting) pathway mediates the biosynthetic transport of vacuolar enzymes, its membrane dynamics and mechanism are almost the same as those of selective autophagy.

Taking out the trash is a vital procedure for cells, as well as for maintenance of your household, and there are cases where autophagy is implicated in human diseases. For instance, mitochondria are intensely active metabolically, and experience a lot of wear and tear. Your cells take old, busted mitochondria, tag them with proteins, and recycle them with a specific subset of autophagy called mitophagy, or mitochondria-eating. Some forms of Parkinson’s disease seem to be caused by defects in the mitophagy machinery, causing defective mitochondria to accumulate in the cell and impairing normal function.

Autophagy also seems to have some complex roles in cancer. It can be a good thing, in that early on if defective proteins and organelles accumulate, they can be sensed and destroyed, so autophagy in that case is a defense against cancer. However, cancer can also subvert that machinery and route the cell’s defenses right into the trash.

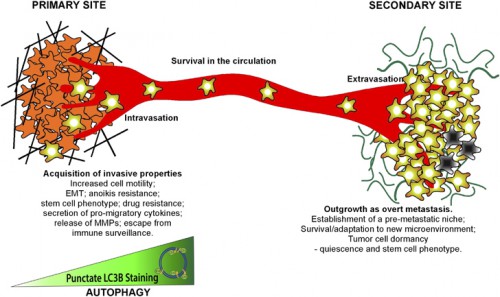

But also, autophagy seems to be involved in every step in cancer metastasis. This shouldn’t be a surprise, since autophagy is used to regulate the activity of the cell in all kinds of behaviors.

Schematic illustrating roles of autophagy in the metastatic cascade. Autophagy increases as tumor cells progress to invasiveness and this in turn is linked to increased cell motility, EMT, a stem cell phenotype, secretion of pro-migratory factors, release of MMPs, drug resistance and escape from immune surveillance at the primary site in some tumors. Many aspects of these autophagy-dependent changes during acquisition of invasiveness also likely contribute to the ability of disseminating tumor cells to intravasate, survive and migrate in the circulation before extravasating at secondary site. At the secondary site, autophagy is required to maintain tumor cells in a dormant state, possibly through its ability to promote quiescence and a stem cell phenotype, that in turn is linked to tumor cell survival and drug resistance. Emerging functions for autophagy in metastasis include a role in establishing the pre-metastatic niche as well as promoting tumor cell survival, escape from immune surveillance and other aspects required to ultimately grow out an overt metastasis.

It may also affect Crohn’s disease and other inflammatory syndromes. There are mutated proteins associated with Crohn’s that are part of the autophagy pathway; macrophages carrying these mutations deliver bigger doses of inflammatory cytokines when stimulated. Selective autophagy plays a role in regulating the balance of exports from the cell.

Those are the mild diseases caused by defects in this pathway. Look up Vici syndrome, a heritable disorder that causes devastating problems for those afflicted. It’s caused by mutations in the EPG5 gene, which is an important regulator of autophagy.

It’s not just about human diseases, though. Autophagy is universal in eukaryotes: yeast have it, plants have it, animals have it. Genes in the pathway are studied in yeast and nematodes and flies and mice, so this is a common mechanism of regulating the internal traffic of the cell.

Jiang P, Mizushima N (2014) Autophagy and human diseases. Cell Res 24(1):69-79.

Nakatogawa H, Suzuki K, Kamada Y, Ohsumi Y (2009) Dynamics and diversity in autophagy mechanisms: lessons from yeast. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10(7):458-67.

Mowers EE, Sharifi MN, Macleod KF (2016) Autophagy in cancer metastasis. Oncogene doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.333.

This work is incredible. The actual mechanism of life.

Thank you for such a clear explanation of what autophagy is. Even a layman like me understood it, someone who had to give up studying Biology when I was 12 so that I could study Latin!