We all know that some hot days feel fairly comfortable while others at the same temperature feel clammy and muggy. We tend to identify the difference as caused by the relative humidity and this sentiment is often expressed by the statement “It’s not the heat, it’s the humidity”. But actually, the humidity is not the best measure to use to measure the level of discomfort. A better measure is the lesser-known ‘dew point’. The National Weather Service explains what ‘dew point’ is and why this is the case.

The dew point is the temperature the air needs to be cooled to (at constant pressure) in order to achieve a relative humidity (RH) of 100%. At this point the air cannot hold anymore water in the gas form. If the air were to be cooled even more, water vapor would have to come out of the atmosphere in the liquid form, usually as fog or precipitation.

The higher the dew point rises, the greater the amount of moisture in the air. This directly effects how “comfortable” it will feel outside. Many times, relative humidity can be misleading. For example, a temperature of 30 and a dew point of 30 will give you a relative humidity of 100%, but a temperature of 80 and a dew point of 60 produces a relative humidity of 50%. It would feel much more “humid” on the 80 degree day with 50% relative humidity than on the 30 degree day with a 100% relative humidity. This is because of the higher dew point.

So if you want a real judge of just how “dry” or “humid” it will feel outside, look at the dew point instead of the RH. The higher the dew point, the muggier it will feel.

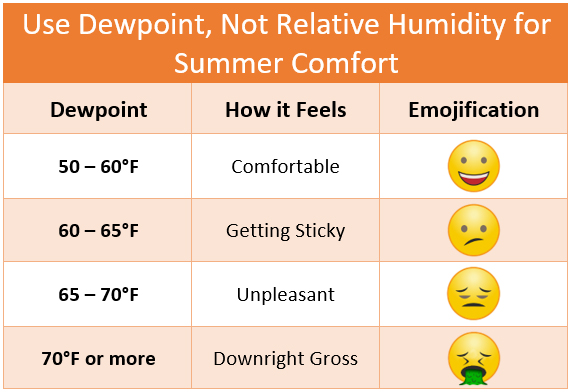

General comfort levels that can be expected during the summer months:

- less than or equal to 55: dry and comfortable

- between 55 and 65: becoming “sticky” with muggy evenings

- greater than or equal to 65: lots of moisture in the air, becoming oppressive

For those who like to get their information in emoji form, here’s one.

I noticed this myself about ten days ago when it was hot. I was outside and noticed that it felt very muggy. When I checked, the temperature was 91F but the relative humidity was only 42%, which would normally be felt as comfortable. But the dew point was 65F.

Of course the three things (actual temperature T, the dew point temperature TD, and the relative humidity RH) are related. Given any two, you can calculate the third. This website enables you to obtain any one of them given the other two and provides the actual formulas used, where temperatures used in the formulas are measured in Celsius.

The reason why the dew point may be a better indicator than the relative humidity, even though they are related to each other, is that the relationship is not linear. For a given temperature, the relative humidity rises more rapidly as the dew point rises.

This seems to me like a roundabout way of saying the total amount of water in the air (or density or whatever). The dew point just the contour of temperature as a function of humidity where humidity = 100%.

I didn’t read closely enough and it seems they do indeed say that: “The higher the dew point rises, the greater the amount of moisture in the air.”

Perception of temperature also has a lot to do with inner states as well -- whether you’re being active and have an elevated heart-rate, etc.

It’s quaint when Americans talk temperature. “°F” is like “thee” and “thou”. Forsooth, ’tis warm!

The temperature/moisture ratio does not completely define comfort levels.

When I moved from inland Mississippi to peninsular Florida, the summer air felt nicer -- though just as humid and a bit higher on the thermometer. But in the Gunshine State, we almost always have a slight breeze, just enough to make the Spanish moss sway a little, whereas back in Magnoliastan the hot air and all the water in it Just Sit On You.

Good explanation.

It also explains how a air conditioning unit is more than just dropping the temperature. A/C , when properly sized and working properly, pulls water out of the air.

A common problem down here in Florida is that people think that a more powerful A/C unit is better. The problem is that the A/C unit works on a thermostat that measures temperature and largely ignores humidity. A large and powerful A/C unit drops the temperature so quickly that there is not enough time to condense and drain off the water. Temperature goes down but the humidity stays the same.

The result is that the people feel uncomfortable and, trying to feel better, drop the setting on the thermostat a few more degrees. The result is a building like a cold, damp cave.

A trick for testing if the A/C unit is oversized is to simply block off about a third of the air return inlet. Cardboard and masking tape work well but anything that blocks air will work. Let the A/C unit run. It will run far less efficiently and will be forced to run longer. This extra time gives it time to condense and drain off the water to bring the humidity down.

Another clue is if the air feels better with a dirty filter in it and clammy if the filter is replaced or cleaned. Same principle. as the test above.

Then there is the problem here in the southwest where the dew point gets down into the single digits. The skin ends up cracking and flaking, sinuses and mouth get uncomfortably dry, even if the temperature is “mild”, like 75F with a dew point of 4F.