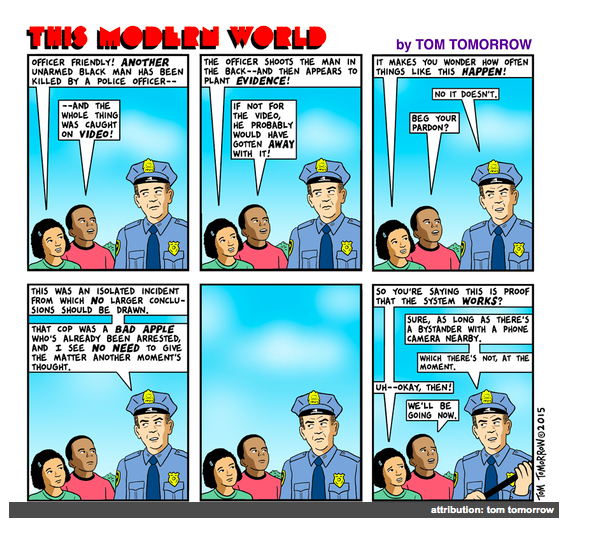

Once in a while, you get a revealing glimpse about the nature of privilege, especially the fact that those who are the biggest beneficiaries of it are also often the most oblivious. David Brooks, the kind of person who is seen as a serious thinker by The New York Times and NPR, has a column on the new recommendations requiring police to war bodycams that is very revealing of the mindset of the privileged.

He begins by sadly acknowledging that the use of such cameras is necessary because recent events have shown that they will likely result in less abuse by police and less confusion about what happened in any confrontation. But at the same time, he sees a serious downside in the introduction of cameras as undermining police-civilian relationships and a loss to privacy.

The cameras will undermine communal bonds. Putting a camera on someone is a sign that you don’t trust him, or he doesn’t trust you. When a police officer is wearing a camera, the contact between an officer and a civilian is less likely to be like intimate friendship and more likely to be oppositional and transactional. Putting a camera on an officer means she is less likely to cut you some slack, less likely to not write that ticket, or to bend the regulations a little as a sign of mutual care.

Putting a camera on the police officer means that authority resides less in the wisdom and integrity of the officer and more in the videotape. During a trial, if a crime isn’t captured on the tape, it will be presumed to never have happened.

Cop-cams will insult families. It’s worth pointing out that less than 20 percent of police calls involve felonies, and less than 1 percent of police-citizen contacts involve police use of force. Most of the time cops are mediating disputes, helping those in distress, dealing with the mentally ill or going into some home where someone is having a meltdown. When a police officer comes into your home wearing a camera, he’s trampling on the privacy that makes a home a home. He’s recording people on what could be the worst day of their lives, and inhibiting their ability to lean on the officer for care and support.

Cop-cams insult individual dignity because the embarrassing things recorded by them will inevitably get swapped around. The videos of the naked crime victim, the berserk drunk, the screaming maniac will inevitably get posted online — as they are already. With each leak, culture gets a little coarser. The rules designed to keep the videos out of public view will inevitably be eroded and bent.

Does he really think that poor and people of color have an “intimate friendship” with the police? The slogan “to serve and protect” is associated with police departments but who are the people who feel they are being served and protected by the police? And who are the people whom the police think they are serving and protecting? What Brooks does not seem to realize is that it is people like him who are less likely to pulled over in the first place and if they are, are more likely, in his words, to be cut some slack, to not get a ticket, or to have regulations bent as a sign of “mutual care”. It is because the police know that obviously rich people are the ones they are meant to serve and protect.

His concerns about privacy are also revealing. People like Brooks have little fear that they will be shot dead by police. They do not have broken tail lights, warrants for non-payment of fines, and the other small infractions of the law that can make even a minor traffic stop a major concern for poor people. But people of his class could well be stopped for driving drunk or have police come to their homes because of some intra-family disturbance, because such things can happen to people of any class. Videos of such things can be very embarrassing to prominent people. For people like Brooks, being caught drunk or in an otherwise embarrassing situation is a far greater risk than being shot by police.

In the 1959 comedy Our Man in Havana that takes place in pre-revolutionary Cuba, there is an interesting exchange between the chief of police and someone working for the British secret service. They are talking about a Cuban engineer whom the British tried to recruit as a spy.

British spy: “How did you make the engineer talk? Thumb screws?”

Chief of police: “The engineer does not belong to the torturable class.”

British spy: “Are there class distinctions in torture?”

Chief of police: “Some people expect to be tortured. Others are outraged by it. One never tortures except by mutual agreement.”

British spy: “Who agrees?”

Chief of police: “Usually the poor.”

The police know that people like Brooks do not belong to the torturable class nor to the shootable class not to the ‘assault and throw in jail’ class. They would be outraged by it. But he does belong, like all of us, to the embarassable class. And so naturally he sees that as the main source of concern.

“Once in a while, you get a revealing glimpse about the nature of privilege, especially the fact that those who are the biggest beneficiaries of it are also often the most oblivious.”

--

Oh you get that ‘glimpse’ every time Brooks opens his mouth…It’s his entire persona: Clueless privilege dude

Did you see that Walter Scott’s broken taillight didn’t even violate South Carolina law? The cop didn’t even have probable cause to stop him. See Ignorance of the Law on Slate.

To the argument that body cameras would build a barrier between police and the public, I suggest that good fences make for good neighbors.

The “Our Man in Havana” exchange reminds me of Matt Taibbi’s chats about his book The Divide. https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=matt+taibbi+the+divide When he talks to prosecutors about white collar criminals going to prison, and they respond by basically saying something like “Prisons are terrible places; ‘they’ don’t belong in prison” … implication being that there are some people who do “belong in prison”.

“Putting a camera on someone is a sign that you don’t trust him,”

Is Brooks aware of all the cameras out there already pointed at non-police? Hey, if there is a camera war then the cops started it.

Ahcuah,Scott was a black man driving an expensive car. There’s your probable cause right there.

*lolsob*

Well, there are real privacy concerns with putting cameras on police, but not for the reasons that Brooks mentions in the article. A cop walking into your house would imply a camera sweeping your house, for instance. There are privacy concerns there.

But Brooks doesn’t really mention that.

So, being under surveillance makes a cop feel untrusted? Tell that to every warehouse worker, bank teller and loads of other jobs that don’t run the high risk of violent escalation. Trust but Verify sounds like a very good idea.

Perhaps with mandatory streamed video monitoring we’d see more ticketing of drunk judges and senators along with the disciplining of misbehaving cops. Less privacy is not always a bad thing; it helps us adjust our perceptions to reality allowing the creation of better mitigation strategies and laws.

I’d also like to see some money going toward de-escalation training. What I commonly see in police abuse videos is a “Obey now or i escalate” mindset of petty bully power trips, not one of “protect and serve”.