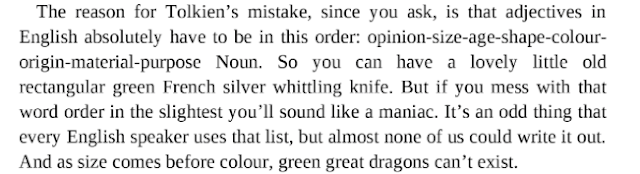

A lot of my friends and acquaintances have been Facebook-sharing the following excerpt from a book by Mark Forsyth, The Elements of Eloquence:

Forsyth gives a good general rule for English, but like most grammatical rules, it’s easy to find exceptions. For example, the American poet Benjamin Ivry wrote, in his poem “Ici Mourut Racine”, of a “square little cottage”.

So a challenge to readers: come up with the best natural-sounding exception to Forsyth’s rule of English. You get bonus points if you violate Forsyth’s order in multiple ways, and even more bonus points if you can find it in the published work of a native English-speaking author. No prizes for citing non-native speakers clearly lacking English skills.

I do not know, but this supposed-“rule” (which I’ve do not recall ever hearing before) sounds like something derived from Latin. There was a plague of that nonsense back in the the 19th(?)C., all of which can be dismissed by simple observation “Latin is not English”.

blf, #1

It’s not a borrowing from Latin this one. Word order in inflected languages – Latin included – is generally a lot freer, and Latin adjectives usually go after the noun, not before it. In fact, in Latin you can vary the emphasis on particular words by moving them to emphatic positions at the beginning and end of a phrase – so if you did pile up the adjectives after a Latin verb then the ones at the beginning and end of the selection would be the most significant ones.

English can put adjectives after a verb too – “an old, wooden staircase, ascending perilously, polished to a shine”. Which rather complicates the “rule”. And not all English adjectives fit one of those eight categories. Some imply conditions, qualities or characteristics that cannot be classified thus – what about “fast”? or “rickety”? or “salubrious”? or “running”? Most participles tend to fall into this category. And some adjectives can imply more than one category. “Silver”, from the above example, can be either a colour or a material for instance. Is it that obvious that a Spanish silver fork is made from silver (mined in Spain?), but a silver Spanish fork is just silver-coloured? I don’t think it is.

One of the charms of heraldry, in addition to the archaic adjectives, is their bizarre positions (for native speakers of modern English): “Paly argent and azure, a bend gules, and on the bend three eagles Or”.

Also, adjectives can associate strongly with nouns to create a semantic unit that gets further modified. Such as “roll out the Hollywood red carpet” or “he swung his Toledo steel short sword”. And you can use word order for emphasis in English to some extent: “crescent-shaped ancient swords are more elegantly made than straight-bladed ones”.

If one has an array of great dragons, how else could one verbally draw attention to the green one(s)?

The example offered, to me at least, makes the writer sound like a maniac (or rather, sound incompetent). Knives aren’t rectangular. Knives made to whittle wood aren’t made of silver (it’s too soft). If it’s made of silver, how can it be green? Is it the handle that’s supposed to be green, and maybe rectangular?

Anyway, it just sounds weird.

As for counterexamples to the proffered order: The phrase “a long strange trip” has the size before the opinion, and “a strange long trip” sounds wrong.

I see that Language Log has tackled the claim, with some data.

From an article about the Queen’s corgis, as English a subject as English was ever written on: “No animal is more synonymous with royalty than these squat little pups…”

Green great dragons may be an endangered species, but red giant stars are common enough. Given the lamentable state of science funding, the astronomers who study them often drive sagging, rusty old cars.

Apparently some linguists feel inserting commas let you do pretty much what you want in terms of word order.

I have to recommend this nice video on the same topic: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mTm1tJYr5_M&list=PL96C35uN7xGLDEnHuhD7CTZES3KXFnwm0&index=8

The other related linguistic videos are good too – the one on the colour “grue” is one of my favourites.