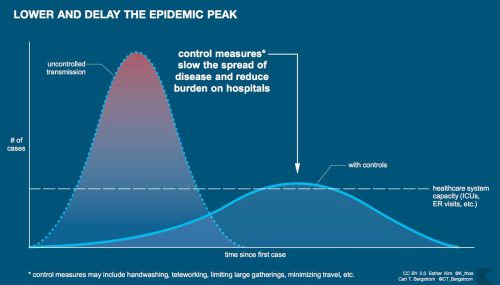

Yikes. I just read this comment about the coronavirus shut down in Poland — 22 cases in the whole country, so all university classes are suspended for the next month. That’s taking the issue seriously and taking major steps to slow the spread of the disease.

At my university, it’s only provosts and deans and chancellors and department heads talking about contingency plans, with no imminent threat of a shut down. But it could happen! With the number of cases doubling every week, I might come back from Spring Break to find my students have been ordered to stay away. I’ve scribbled up a quick contingency plan for my genetics course, just in case.

Contingency plan for Genetics (Biol 4312)

Genetics is an unusual lab course in that it already doesn’t fit the mold of the weekly intensive lab session. We’re working with Drosophila, and are at the mercy of their 9 day reproductive cycle, so we have to be more flexible. Typically, we meet for a half hour to an hour at the scheduled lab time, during which I explain the steps that the students need to take that week. The students need to come in frequently during the course of that week to maintain their flies, set up crosses when they’re ready, and count phenotypes. Some weeks this is a light load, coming once or twice on their own time to check on flies; other weeks they may have to come in 3 or 4 times a day to collect flies for a cross; and on several occasions they have to come in for long sessions of fly screening. The variability and flexibility suggest one fairly non-disruptive way to protect students.

Staggered, scheduled lab times. To minimize exposure, I could set up specific, individual lab times for each student. Right now, it’s a free-for-all with students doing their work whenever they can, but we could switch to exclusive lab sessions for each. So far this semester we have completed one whole experiment involving 3 different crosses, so students are familiar with the details of the methods, and they are experienced enough to not need direct instruction from me; I could manage with an explicit set of detailed instructions on Canvas for the steps in the next experiment.

They would still be using a shared lab facility, so we’d couple this scheduling with instructions on using sanitizers and sterilizing lab benches with alcohol between students.

In a worst case scenario, in which the university is shut down, another alternative is:

Drosophila genetics kits. I could assemble a kit with two fly stocks, a half dozen fly bottles, a small supply of medium, some anesthetic, and a hand lens for each student or pair of students. They could then carry out the whole experiment at home, again with detailed week-by-week instructions on Canvas. Data would be shared between students online.

Potential problems: Lack of an incubator would mean developmental rates might vary significantly. A hand lens is going to make it harder for students to score phenotypes. Currently, if one student’s cross fails, they can share specimens with other students and complete the experiment; in isolation, if one cross fails, they’ll be unable to finish. The final assays are somewhat labor intensive, alleviated by the fact that a group can share the load of counting thousands of flies.

Please note that these alternatives are only feasible because the students have completed an experiment with multiple crosses in the first half of the semester, with direct instruction and demonstration from me on how to set up a cross, how to maintain flies, and how to analyze phenotypes. The second half of the semester is repeating these same methods with a very different kind of cross and different mutant phenotypes. These stop-gap procedures would not be applicable to teaching a full semester lab course in fly genetics.

Setting up staggered lab times looks like wishful thinking now, if entire countries are locking out universities in the face of the threat. I might have to spend my spring break boxing up flies and media for distribution.