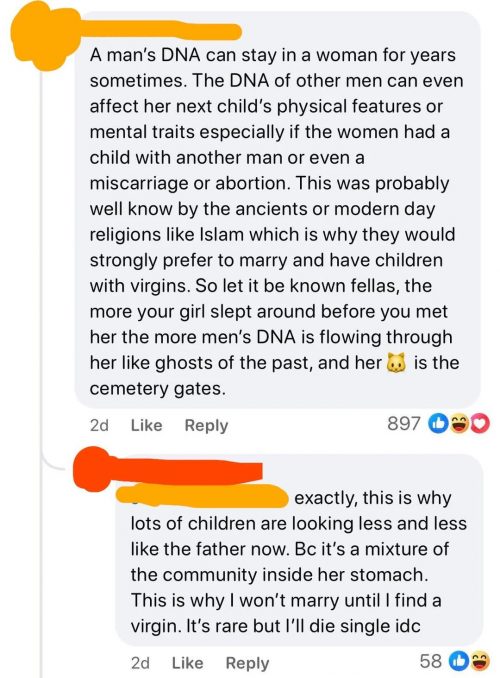

I keep seeing lies about biology like this on social media. This is all wrong.

A man’s DNA can stay in a woman for years sometimes. The DNA of other men can even affect her next child’s physical features or mental traits especially if the women had a child with another man or even a miscarriage or abortion. This was probably well know by the ancients or modern day religions like Islam which is why they would strongly prefer to marry and have children with virgins. So let it be known fellas, the more your girl slept around before you met her the more men’’s DNA is flowing through her like ghosts of the past, and her 🐱 is the cemetery gates

I have embryology textbooks all over the place, and this is what they have to say.

Sperm can survive in a man’s testicles for a few months. That’s a pleasant environment for a sperm cell, but even there they’re undergoing a slow process of maturation, and are eventually going to be broken down and resorbed. That’s the maximum longevity for these cells.

A woman’s reproductive tract is warm and moist and allows for limited survival, but is adapted to protect her from infections by maintaining a mildly acidic environment. It’s a somewhat hostile place that has to tolerate foreign cells, but not for long — sperm will last for 3-5 days, not years.

You may have heard of a phenomenon called microchimerism, in which fetal cells, shed during pregnancy, persist for years. These are somatic cells, not sperm cells. Sperm cells are highly specialized and have minimized their cytoplasm and cannot survive for that long.

The textbooks usually mention that sperm can survive for about an hour outside of a human body. That’s optimistic (or pessimistic, if you want to avoid pregnancy). Evaporation or absorption of the surrounding fluid is going to kill the little fuckers pretty fast.

It’s clear how these bad ideas get around — the hint is in the text. The “ancients” or “religion” are terrible sources of information, since none of them had anything but the vaguest notion of how reproduction or inheritance work, and didn’t even know about the existence of cells until, at best, three hundred years ago. Another obvious source is a cultural bias favoring virginity (a bogus concept already), and this is an attempt to rationalize that belief with made-up “facts”.