And then I felt intimidated.

(via Echinoblog)

I don’t mind the portrayals of dinosaurs in coitus, but look at those two: did they have to have such lecherous grins?

The disturbing thing is that that is the same expression they’d have on their face when they were ripping up a hadrosaur. Being a monkey-faced primate with a dependence on facial expressions really sets up inappropriate expectations when looking at stone-faced reptiles.

We had another fun Google+ Hangout this morning with Esteleth, James Rook, Tommy Leung, and Yankee Cynic, building on a couple of articles I mentioned before. Basically, we talked about the attractiveness of the premises of evolutionary psychology vs. the extravagance of their conclusions, and the unreliability of brains and how we have to work hard to overcome them. It turned into a kind of discussion about psychology, of all things.

And now you can watch it all, too.

Isn’t it amazing how you can assemble a small group of people, give them the seed of an idea, and then they can go on to talk about it for an hour, easy?

We’ll probably do another one in about two weeks. Make suggestions! I’m also planning to do the next one at sometime in my local evening, so maybe we can bring in an Australian or two.

Oy, singularitarians. Chris Hallquist has a post up about the brain uploading problem — every time I see this kind of discussion, I cringe at the simple-minded naivete that’s always on display. Here’s all we have to do to upload a brain, for instance:

The version of the uploading idea: take a preserved dead brain, slice it into very thin slices, scan the slices, and build a computer simulation of the entire brain.

If this process manages to give you a sufficiently accurate simulation

It won’t. It can’t.

I read the paper he recommended: it’s by a couple of philosophers. All we have to do is slice a brain up thin and “scan” it with sufficient resolution, and then we can just build a model of the brain.

I’ve worked with tiny little zebrafish brains, things a few hundred microns long on one axis, and I’ve done lots of EM work on them. You can’t fix them into a state resembling life very accurately: even with chemical perfusion with strong aldehyedes of small tissue specimens that takes hundreds of milliseconds, you get degenerative changes. There’s a technique where you slam the specimen into a block cooled to liquid helium temperatures — even there you get variation in preservation, it still takes 0.1ms to cryofix the tissue, and what they’re interested in preserving is cell states in a single cell layer, not whole multi-layered tissues. With the most elaborate and careful procedures, they report excellent fixation within 5 microns of the surface, and disruption of the tissue by ice crystal formation within 20 microns. So even with the best techniques available now, we could possibly preserve the thinnest, outermost, single cell layer of your brain…but all the fine axons and dendrites that penetrate deeper? Forget those.

We don’t have a method to lock down the state of a 1.5kg brain. What you’re going to be recording is the dying brain, with cells spewing and collapsing and triggering apoptotic activity everywhere.

And that’s another thing: what the heck is going to be recorded? You need to measure the epigenetic state of every nucleus, the distribution of highly specific, low copy number molecules in every dendritic spine, the state of molecules in flux along transport pathways, and the precise concentration of all ions in every single compartment. Does anyone have a fixation method that preserves the chemical state of the tissue? All the ones I know of involve chemically modifying the cells and proteins and fluid environment. Does anyone have a scanning technique that records a complete chemical breakdown of every complex component present?

I think they’re grossly underestimating the magnitude of the problem. We can’t even record the complete state of a single cell; we can’t model a nematode with a grand total of 959 cells. We can’t even start on this problem, and here are philosophers and computer scientists blithely turning an immense and physically intractable problem into an assumption.

And then going on to make more ludicrous statements…

Axons carry spike signals at 75 meters per second or less (Kandel et al. 2000). That speed is a fixed consequence of our physiology. In contrast, software minds could be ported to faster hardware, and could therefore process information more rapidly

You’re just going to increase the speed of the computations — how are you going to do that without disrupting the interactions between all of the subunits? You’ve assumed you’ve got this gigantic database of every cell and synapse in the brain, and you’re going to just tweak the clock speed…how? You’ve got varying length constants in different axons, different kinds of processing, different kinds of synaptic outputs and receptor responses, and you’re just going to wave your hand and say, “Make them go faster!” Jebus. As if timing and hysteresis and fatigue and timing-based potentiation don’t play any role in brain function; as if sensory processing wasn’t dependent on timing. We’ve got cells that respond to phase differences in the activity of inputs, and oh, yeah, we just have a dial that we’ll turn up to 11 to make it go faster.

I’m not anti-AI; I think we are going to make great advances in the future, and we’re going to learn all kinds of interesting things. But reverse-engineering something that is the product of almost 4 billion years of evolution, that has been tweaked and finessed in complex and incomprehensible ways, and that is dependent on activity at a sub-cellular level, by hacking it apart and taking pictures of it? Total bollocks.

If singularitarians were 19th century engineers, they’d be the ones talking about our glorious future of transportation by proposing to hack up horses and replace their muscles with hydraulics. Yes, that’s the future: steam-powered robot horses. And if we shovel more coal into their bellies, they’ll go faster!

A very familiar story: a creationist is told that her views are unsupported by any legitimate science, and in reply she rattles off a list of creationist “scientists”.

Here we are told by a creationist housewife — as she describes herself — defending her belief that the Giant’s Causeway is only as old as the Bible says it is, a claim which assumes, of course, that there is a definite chronology in the Bible which can be used to date the age of the earth, and that this chronology, such as it is, supersedes all other forms of chronology, because the Bible is, after all, the inerrant word of God. In response to Richard Dawkins claim that reputable scientists all agree that the earth is billions of years old, our doughty housewife responds with: “That’s a blatant lie,” And then she lists four “scientists” who accept the creationist dating of the age of the earth (and she might well have named more, because, if you google these names, you end up on sites with many more).

The word “scientist” is simply a label, and if you ignore its meaning, you can stick it on anything. I’ve always considered a scientist as someone who follows a rational program of investigation of the real world, and that the word describes someone carrying out a particular and critical process of examination. But apparently, to people with no well-informed knowledge of its meaning, “science” and “scientist” are just tags you stick on really smart people who reach a conclusion you like, or who have done the academic dance to get a Ph.D. as a trophy to stick on the end of your name.

That’s a shame.

Let me explain the difference with an analogy.

A carpenter is a person who practices a highly skilled trade, carpentry, to create new and useful and lovely things out of wood. It is a non-trivial occupation, there’s both art and technology involved, and it’s a productive talent that contributes to people’s well-being. It makes the world a better place. And it involves wood.

A pyromaniac is a person with a destructive mental illness, in which they obsess over setting things on fire. Most pyromaniacs have no skill with carpentry, but some do; many of them have their own sets of skills outside of the focus of their illness. Pyromania is destructive and dangerous, contributes nothing to people’s well-being, and makes the world a worse place. And yes, it involves wood, which is a wonderful substance for burning.

Calling a creationist a scientist is as offensive as praising a pyromaniac for their skill at carpentry, when all they’ve shown is a talent for destroying things, and typically have a complete absence of any knowledge of wood-working. Producing charcoal and ash is not comparable to building a house or crafting furniture or, for that matter, creating anything.

You can’t call any creationist a scientist, because what they’re actively promoting is a destructive act of tearing down every beautiful scrap of knowledge the real scientists have acquired.

Give me grizzled, battered, and well-worn. Plasticky, smooth, and fresh is so freaking uninteresting.

I’m always telling people you need to understand development to understand the evolution of form, because development is what evolution modifies to create change. For example, there are two processes most people have heard of. One is paedomorphosis, the retention of juvenile traits into adulthood — a small face and large cranium are features of young apes, for instance, and the adult human skull can be seen as a child-like feature. A complementary process is peramorphosis, where adult characters appear earlier in development, and then development continues along the morphogenetic trajectory further than normal, producing novel attributes. You may have encountered examples of this in fiction: the best known are the Pak Protectors in Niven’s science-fiction stories, which are the result of longer-lived humans continuing the processes of aging to reach a novel form. There’s also the story of After Many a Summer Dies the Swan, a novel by Aldous Huxley, in which a paedomorphic species (a human) lives for a very long time and develops to reach the ancestral state — a more primitive apelike form.

Just to make it more complicated, though, this isn’t to say that evolution proceeds by arresting the whole of development, turning the adult into an overgrown baby. What’s going on here is that genes that control the rate of development are being tweaked by genetic change, and there are many of those genes. There can be all sorts of mixing and matching — one organ or feature can undergo paedomorphosis in a species at the same time that another is undergoing peramorphosis.

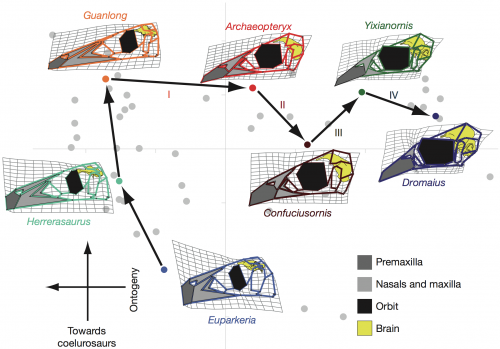

A beautiful example has recently been published in Nature: the evolution of the avian skull. The postcranial bird skeleton can’t be neatly categorized as changes in rate: wings, the correlated changes in the pelvis and thorax, all that is a messy collection of novelties. The skull, though, can at least be broken down into a couple of key avian adaptions: brains and beaks. The cranium has gone through a set of changes with all the behavioral and sensory changes (big eyes, motor aspects of flight, navigation), while the beak has obviously diversified for different feeding strategies. The beak has changed to take over the manipulatory role lost as forelimbs became wings.

Here’s how the role of heterochrony (changes in rate of development) of different species was determined. The authors collected quantitative morphological data on a set of fossil dinosaurs and birds and extant birds for which there were both embryological and adult data. There are some straightforward observations that just leap out at you. For instance, embryonic alligator skulls have the same proportions as the skull of adult Confuciusornis, a crow-sized bird from the Cretaceous.

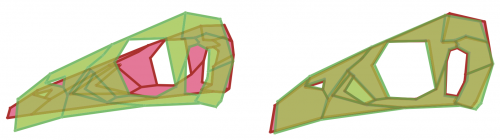

Another common and long-hallowed technique in developmental biology is to trace a standard skull onto a 2-D grid and then determine what distortions of the grid are necessary to reshape the skull into a specific form. This method makes the stretching and skewing and compression that had to have occurred over time to sculpt these skulls from an ancestor. Here are the ontogenetic changes for different species, illustrating how they changed shape as they grew up.

If you can do this kind of assessment of transformations over development, you can also do it over phylogeny. Below are shown the trends observed in dinosaur and avian evolution.

The coordinate system on which those skulls are mapped is a little tricky to explain. With all the numerical data available from their skull measurements, the authors did a principal component analysis, determining metrics that accounted for most of the variability between skulls. What they found were two axes of change: one is in the shape of the cranium, which exhibited paedomorphic patterns of change (although the contents of that cranium, the brain, is known to have undergone more complex heterometric change); the second was in the beak, which shows a pattern of peramorphic change.

But that’s the cool thing about this! We can quantitatively describe the plastic changes in the shape of the skull over evolutionary history as largely the product of two trends: a retention of the bulbous embryonic shape of the skull, and increased extension of the facial bones to form a beak. It’s not magic, it’s the expected incremental shifts in shape over long periods of time, in which we can actually visualize the pattern of transformation.

Now we just need to work out the genes behind these morphological changes, and their mode of action. That’s all. Hey, I think the developmental biologists have at least a century of gainful employment ahead of them…

Bhullar BA, Marugán-Lobón J, Racimo F, Bever GS, Rowe TB, Norell MA, Abzhanov A (2012) Birds have paedomorphic dinosaur skulls. Nature doi: 10.1038/nature11146. [Epub ahead of print]

I’m going to be doing a bit of traveling again starting in August. I’ll be in Washington DC on the 18th, to do a fundraiser lunch for CFI-DC, and I’ll also be doing a talk later that afternoon. The talk title is “Life is Chemistry“, and I’ll be explaining why material causes are sufficient to explain this phenomenon we call life — no ghosts, spirits, souls, or magic Frankensteins in the sky to make it all happen.

Sign up for tickets now! Last time I was there they sold out.

I think she’s just got one thing on her mind.

The insects crawling all over it add a creepy touch, though.

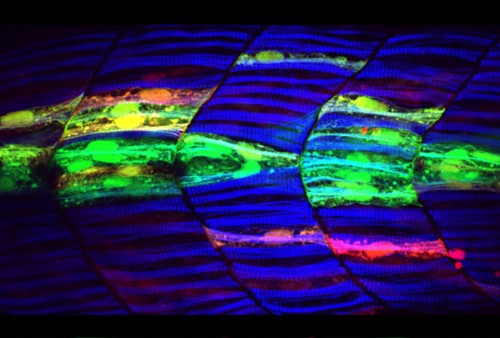

If you ever get a chance, spend some time looking at fish muscles in a microscope. Larval zebrafish are perfect; they’re transparent and you can trace all the fibers, so you can see everything. The body musculature of fish is most elegantly organized into repeating blocks of muscle along the length of the animal, each segment having a chevron (“V”) or “W” shape. Here’s a pretty stained photo of a 30 hour old zebrafish to show what I mean; it’s a little weird because this one is from an animal with experimentally messed up gene expression, all that red and green stuff, but look at the lovely blue muscle fibers stretching across the length of each segment.

But wait—why the chevron shape? Also, the reason I told you to look in a microscope sometime is that a 2-D image can’t illustrate the lovely intricacy of the muscles; they don’t go straight across, but twist in a partial spiral in 3-dimensions. Trust me, it’s beautiful to see. And it’s also nearly universal in chordates — even Amphioxus has this arrangement. And there’s a good biomechanical reason for this arrangment.