Charlie Stross has written a story, A Bird in Hand, which rather pushes a few boundaries. It’s about dinosaurs and sodomy, as the author’s backstory explains. And as everyone knows, every story is improved by adding one or the other of dinosaurs and sodomy, so it can’t help but be even better if you add both.

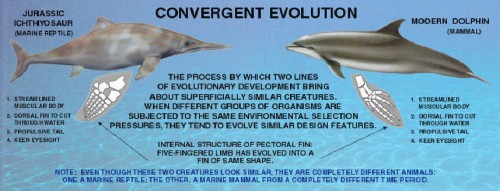

A note of caution, though: Charlie is really, really good at spinning out all the latest scientific buzzwords and deep molecular biological concepts into an extraordinarily plausible-sounding mechanism for rapidly recreating a dinosaur — it’s much, much better than Crichton’s painfully silly and superficial dino-blood-from-mosquitoes-spliced-with-frog-DNA BS — but I was a bit hung up on poking holes in it. It won’t be quite that easy, and it rather glibly elides all the trans-acting variations that have arisen in 70 million years and the magnitude of the developmental changes. But still, if we ever do manage to rebuild a quasi-dinosaur from avian stock, that’ll be sort of the approach that will be taken, I suspect. Just amplify the difficulty a few thousand fold.

Also, it’s way too technical to survive in the movie treatment.