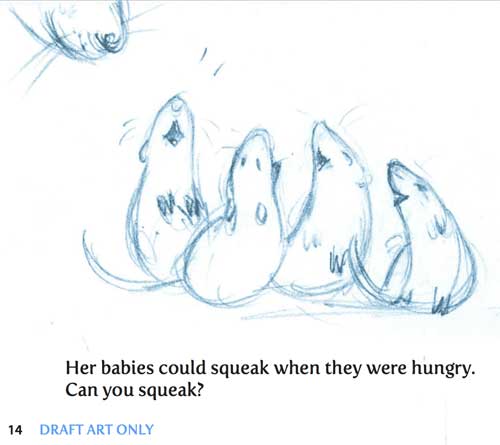

I got to meet someone in Seattle who is working on an evolution book for four year olds — this is a great idea, because I remember shopping for kids’ books and their usual idea for introducing zoology was something about Noah’s Ark. But the real story is so much more interesting!

Rough sketches of the book, Grandmother Fish, are available online; those aren’t the final drawings, and the work will be done by KE Lewis, once funding is obtained. You can see the challenges of getting a sophisticated scientific concept across to very young children, but I think the current story does the job very well.

There will be a kickstarter later this week to get the project off the ground.