The Probability Broach, chapter 14

Win, Ed and Lucy are face-to-face with John Jay Madison, the mastermind who’s responsible for the repeated assassination attempts that Win has been dodging ever since he arrived in this world.

And Madison doesn’t care whether they know it or not. Although he offers rote denials that he had anything to do with the attacks, he leers at them with superficial politeness that disguises barely concealed malice. He relishes the chance to taunt them, knowing they have no proof:

He rose, thrust his hands in his pockets, and paced, almost talking to himself, his eyes intent on some other place, some other time. “Inevitably, your investigations will reveal that my real name isn’t John Jay Madison. I was born Manfred, Landgraf von Richthofen. Quite a mouthful, isn’t it? It was, at one time, a name and family of some influence in Prussia, and of not inconsiderable wealth. The War changed that, of course. So, with perhaps a false start or two, I came to America to repair my fortunes.”

He spread his arms. “As you can see, I have, to a certain extent, accomplished that. I changed my name because John Jay and James Madison were, in my view, men of merit, of historical importance to both my homeland and this organization—certainly very American, something I was determined to become and rather easier to pronounce.”

He remarks that he almost named himself after Alexander Hamilton, but decided against it:

“I should have adopted his name, had I dared. I assure you it is held in the esteem it deserves, elsewhere in the System—still, I must be able to buy groceries without arousing counterproductive passions…

Though you may disagree with what I believe, nevertheless I insist on being allowed to believe it, unmolested.”

There’s a tension here which Smith alludes to, but doesn’t resolve.

On the one hand, he’s insistent that in the North American Confederacy, people have total freedom. Everyone can believe, speak and act as they see fit, so long as they don’t harm others. No one is harassed or oppressed because of their opinions. The vast majority of NAC citizens respect these implicit rights, even though there’s no law forcing them to do so.

On the other hand, in this passage, he admits (reluctantly?) that you can be so unlikable that people will ostracize you and refuse to do business with you. And as he said earlier, that’s effectively a death sentence in a society with no safety nets of any kind.

This shows that, even if the author doesn’t want to admit it, an anarcho-capitalist world wouldn’t be a haven of unfettered free speech. It would have a strong drive toward conformity. Everyone would have a natural incentive to fall in line with the dominant opinions of their community, their landlord, or their employer. Whoever you’re dependent on to supply you with the stuff of life, that person would have immense power over you. Why risk pissing them off by being a gadfly?

Arguably, a world with a comprehensive state safety net is more free for this reason. People can say what they wish, safe in the knowledge that their survival doesn’t depend on pleasing the nearest rich guy. No one can snap their fingers and deprive you of food, housing or health care. If there’s a mob at your door, there are (at least theoretically) police you can call who will come and protect you, even if they dislike you.

Some countries, though not the U.S., go even farther in the pursuit of individual rights by instituting employment contracts which guarantee that an employer can only dismiss you for good cause. You can’t be fired just because your boss doesn’t like your face.

Ostensibly to prove he has nothing to hide, Madison gives them a tour of his house—an enormous, rambling mansion that’s more like a museum. There are artifacts from wars and other political events through the decades that the Hamiltonians played a part in. Win notices one especially significant exhibit:

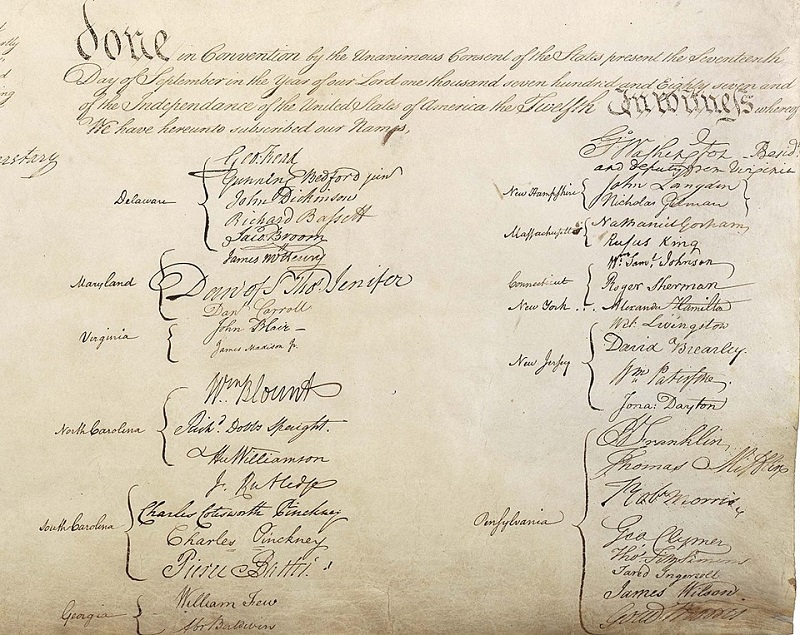

In a sort of chapel, spread like a Bible in a helium-filled glass altar, lay the Constitution of the United States. “We, the People, in order to form a more perfect Union…”

There wasn’t any Bill of Rights.

This is a peculiar line for L. Neil Smith to include.

Obviously, readers are supposed to take this as further proof of Madison’s evil. He wants to conquer the world and impose centralized government, and he venerates the Constitution as symbolic of this. His (presumably deliberate) exclusion of the Bill of Rights shows that his hunger for power isn’t counterbalanced by any concern for people’s rights and freedoms.

But why does Smith think it makes any difference whether it’s there or not?

Lest we forget, Smith described the Constitution as a villainous conspiracy foisted upon an unconsenting nation. He denounced it as an intolerable infringement on freedom, so thoroughly corrupt that it couldn’t be reformed; it had to be scrapped and the country started over from scratch. Those who were responsible for writing it fared little better: George Washington was executed by firing squad, and Alexander Hamilton fled into disgraceful exile.

When you start from that perspective, why does it matter if there’s a Bill of Rights? He’s argued throughout this book that government is evil, full stop. But the fact that Madison, the actual villain of this novel, dislikes the Bill of Rights… doesn’t that imply that maybe the Constitution wasn’t as all-around bad as Smith wants us to think?

This is something he otherwise never concedes: that there can be degrees of government. Maybe, just maybe, it’s possible to have a government which actually values and protects its citizens’ rights, and this is preferable to a government which makes no such guarantees.

New reviews of The Probability Broach will go up every Friday on my Patreon page. Sign up to see new posts early and other bonus stuff!

Other posts in this series:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BfUFh7VAKEI

Are you kidding me? He’s the Red Baron? Aye aye aye…

Why would a Prussian aristocrat admire the US Founding Fathers and revere the constitution in the first place? The founders were liberals, and Prussian aristocrats were reactionaries. And there wouldn’t even be an alliance of convenience between those two groups, considering that the whole reason for this story is that the NAC is more capitalist than OTL America ever was. Frankly, there is no “socialist menace” for them to team up against. (Though ironically, the Prussian government did try to create “bourgeois socialism”— that is, alleviating poverty while keeping the social hierarchy in place— as a relief valve so they could keep their privileges. While Smith likely hates this entirely for not being laissez-faire, I doubt that even then they would team up with Federalists, since the whole point of that was to prevent political freedom by preemptively stopping an antimonarchist rebellion.)

I’m sure I’m beating a dead horse by now, but your middle paragraphs are the very reason why real anarchists want mutual aid and solidarity — basically a safety net without needing a state, as well as other measures to make sure people are provided for even if they piss off the group.

Going back to Madison revering the Constitution and even setting up a shrine to it, even with Prussia’s historical Bismarckian welfare state this would never happen, for these aristocrats don’t want restrictions on what they can do to the lower classes. It’s just Smith grouping all his political enemies into one group. I don’t know if you’ve ever read “What Madness is This?”, an alternate history in which the USA is seen through a glass darkly and all of its culture is flipped to being a totalitarian dictatorship bent on conquest instead of a democracy, but this scene reminds me of that. Funny enough, Alexander Hamilton is a villain there too, but for different reasons.

I guess Smith cares that the Bill of Rights are there both because the Federalists originally thought the Constitution didn’t need it, and also to signal to the real-world readers that Richthofen is the bad guy. After all, freedom of speech and the press and religion, and protection from unreasonable search and seizure and requiring due process are not found in the 1787 constitution, only the 1791 Bill of Rights. Of course, Smith was no radical, but a true radical can and does admire the Bill of Rights for being a step in the right direction even if imperfect, just like the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights are better than what came before them albeit imperfect. A perfect society will never be attained, but a free society would continually critique itself, notice flaws, and work to fix them.

“He’s argued throughout this book that government is evil, full-stop. But the fact that Madison, the actual villain of the novel, dislikes the Bill of Rights… doesn’t that imply that maybe the Constitution wasn’t as all-around bad as Smith wants us to think?”

No. That’s a non-sequitur. I don’t agree with Smith on the Constitution being wholly bad, anymore than the New Deal, but your conclusion doesn’t follow from your premise. Just because a stateless society would be better than a state society does not imply that therefore the state can never do anything good. I can’t speak for propertarians, but the problem anarchists see with welfare states is that they only treat the symptoms and not the root of the problem. Hierarchy is still in place, and capitalism still in place. But most would still prefer a New Deal or Folkhemmet democracy to a laissez-faire capitalist hellscape because there is less poverty. But they do not want people to stop striving for a classless society where everyone has autonomy, since as we know since Reagan onward, if a state can create welfare programs, it can dismantle them with the stroke of a pen.

I agree with Brendan — making this guy the Red Baron is silly. Unless at some point we have him and Win in an aerial dogfight.

I have trouble believing they hate Hamilton so much that just having the name would have everyone cut him out. If someone was named Benedict Arnold I don’t think everyone would assume he was a traitor (though the jokes would be insufferable).

Re the Bill of Rights, it sounds like Win took one glance and spotted the absence of the Bill of Rights. I don’t think it would be that obvious unless he knows it really well. And yeah, from Smith’s/Win’s perspective, worrying about the absence seems unlikely.

Hell, Win was complaining a while back that criminals have more rights than honest people — that doesn’t sound like anyone who takes those rights seriously. Of course plenty of people do seem to think the Bill of Rights doesn’t apply to everyone but Win’s supposed to be the voice of freedom

Why would a Prussian aristocrat admire the US Founding Fathers and revere the constitution in the first place? The founders were liberals, and Prussian aristocrats were reactionaries.

In the eyes of US anti-Federalists (which is what libertarians like Smith were called back then), Federalists (especially Hamilton and the Adamses) were considered too elitist, too urban, multicultural and cosmopolitan, and too respectful toward “Old Europe” monarchs and their tyrannical public-improvement projects. The Jeffersonians, anti-Federalists and slave-owners who took over the US around 1800 were the real reactionaries, and they hated both Federalists and European monarchs for being too progressive and socialist. (And this hatred of Old Europe has continued through WW-II to this day, with Republicans sneering at “Old Europe” (when they questioned Bush Jr’s Iraq war) as gay decadent effeminate surrender-monkeys who’ve been on the verge of civilizational collapse ANY DAY NOW JUST YOU WAIT since about 1968.)

So offhand, I’m guessing Smith was flogging this pompous-barbarian-warmonger-Prussian-aristocrat stereotype from WW-I as a means of demonizing Hamiltonians. Bismarck, both Kaisers AND the Red Baron all rolled into one! It does track within the context of anti-Federalist ideation — which says a lot about anti-Federalist ideation.

A little more commentary: Feral Historian is a Youtuber who reviews sf (books, movies and games – he’s got a lot to say about Warhammer) and he’s just got around to this, as in, this video went up three hours ago as I post this. I like his stuff, even if I don’t agree with some of it.

See what you think.

He does a fascinating and slightly depressing look at media archeology in “Biggs and the End of History”, if you’re looking for something different.

This puts me in mind of the hilarious “Don’t Bang Denmark”, in which self-styled pickup artist Daryush Valizadeh, or “Roosh” to his followers, fails to continue the streak that led to his other books like “Bang Brazil” and “Bang Iceland”, the latter of which one feminist group in that country described as a “rape guide”.

In “Don’t Bang Denmark” the redoubtable Roosh is cockblocked by socialism. I could go into more detail, but just have a read and a laugh at this link: https://dissentmagazine.org/article/cockblocked-by-redistribution/

As I commented earlier:

“Smith’s evil Federalists want to impose the original Constitution, sans amendments (which again reminds us what Smith can’t admit – in the real world, the Constitution wasn’t imposed by fiat on an unwilling populace; it was the result of compromise and negotiation).”

I give Smith credit for having a villain who is at least physically brave; David Weber’s Honor Harrington series piles on one villain, making him not only a slimy aristocrat whose connections save him from a rape conviction, but also a sniveling coward who retreats from battle against orders.

“Why would a Prussian aristocrat admire the US Founding Fathers and revere the constitution in the first place?”

Because Smith’s version of a Prussian aristocrat sees the world just the way Smith does – anyone who is not a propertarian is really a villainous authoritarian, and they all non-propertarians recognize each other as brothers under the skin (touching, isn’t it”)

i can’t believe it, i found an l neil smith product in the wild, on an sff illustration tumblr.

er, in case image don’t embed, a link

Some propertarians (a term I find much more accurate than “libertarian” or “anarcho-capitalist” for them-about the only thing I’d agree with Smith about) do admit that disliked/nonconformist people would suffer in their society. Some, like Hans-Hermann Hoppe, outright embrace it-his vision basically amounts to a series of gated communities free to exclude gays, leftists and other “undesirables”. Once all land is private, they explain, no one has to accept unwanted people. Presumably the homeless etc would be harried into starvation or the most menial jobs to survive as a result. Similar to what you said, Adam, which leftists from every stripe agree on, landlords and employers are powerful people in our lives. Even if you don’t have a dictatorship, most must follow orders or else by them (this could extend to bankers among others too). Propertarians are all about freedom for the owners of property. Those with none or little would accordingly be even more unfree than they are now.

I’m not certain I followed all the previous posts all that closely, but is it possible that in this timeline there never was a Bill of Rights?

In our timeline, the US Constitution was passed with the promise that a Bill of Rights be adopted, but 11 of the 13 colonial state legislatures approved the new US Constitution prior to the federal congress passing the Bill of Rights in September 1789. The fact that 11 of the state legislatures approved the US Constitution meant that it had already become law prior to the Bill of Rights being enacted. By the time the Bill of Rights was ratified in 1791, all state legislatures had ratified the US Constitution (Rhode Island was the last to ratify the US Constitution on May 29, 1790).

Maybe in this timeline Madison never wrote the Bill of Rights, never got it passed through congress, and never sent it the states for ratification. The Federalists made a promise to pass such a series of bills to help define individual rights, but there was nothing which forced them to do so. Mind you, that would make the Jeffersonians quite angry.

But if this happened, this would explain why J.J. doesn’t have the BoR on display, it was never there.

On the other hand, if J.J. has the original US Constitution on display, there wouldn’t be a BoR. That doesn’t exist on the original 5-page document. Even in our time-line the BoR is not on the original documents. Is this a fault in Smith’s research/understanding?

That’s a good point, thanks. IIRC in this (totally silly) timeline, there was a full-blown rebellion against the Federalists’ Constitution, which actually scuttled it very early on. So it’s not at all likely that Madison, or anyone else in the Federalist camp, would have got around to drafting a Bill of Rights in the first place.

(Then again, weren’t the Jeffersonians among the people who WANTED a Bill of Rights because they were afraid of that stronger national government they were about to get? Maybe they got so totally radicalized and carried away that they were no longer willing to accept any compromise?)