So I checked the lead political story on CNN:

CNN poll: It’s a dead heat

Then I checked the lead political story on MSNBC:

NBC/WSJ poll: Very close race with one day to go

Feeling desperate, I even checked Fox News:

CLOSING TIME: In Final Hours, Are

There Still Undecideds Left to Swing?

Do you sense a theme? It’s one that we’ve suffered with for the entire election season: news media that are obsessed with the horse race rather than the issues.

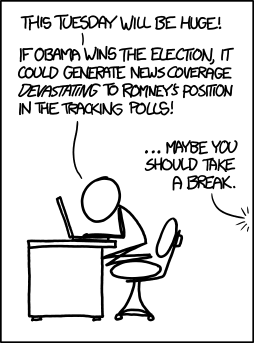

Fuck the media. Only xkcd sees the truth.

And tomorrow is the race itself, with non-stop coverage of exit polls, with maps showing trends, and predictions, and declaring that one state has gone to one candidate or the other — it’s all our media live for, I think, is the ultimate orgasm of who wins, rather than the substance of the consequences of electing either of these people.

I hate them. I hate them all. I will not be watching any of those channels, I will not be visiting their websites at all tomorrow: I am going to vote and then I am going to shut out the yammering ninnies for the whole day, and I will check my newspaper for who the winner was on Wednesday. I might be nice and create an election day thread for you all here, but I will not be reading it myself.

The real election campaign is long over. We were supposed to have news that clearly discussed the differences and similarities between the two. We didn’t get that, so now we get numbers filtered out of noise.

Also, Salon’s top two articles on tomorrow’s election are all about the polls…but they also have an article by Robert Reich on Romney’s destructive policies. More of that, please. I don’t give a damn about the polls — the only one that counts is the election itself.