At age 14, I was sitting in the St. Pius the 10th Catholic Church, and it occurred to me that the apostolic succession and pretty much all of Catholicism could really be founded on a game of telephone.

We all know of the game of telephone: an original message is passed on from person to person, mutating in amusing ways both accidentally and deliberately. Stories of Jesus could have started false (You should have seen the miracle he worked in the previous town!) or could mutate and optimize to most effectively dazzle audiences, even during JC’s lifetime. Not to mention the decades after until they were written down.

And now, 40+ years later, I realize (thanks to Pharyngula) that “provenance” is the word I have needed to describe my path through skepticism and atheism (or agnosticism.)

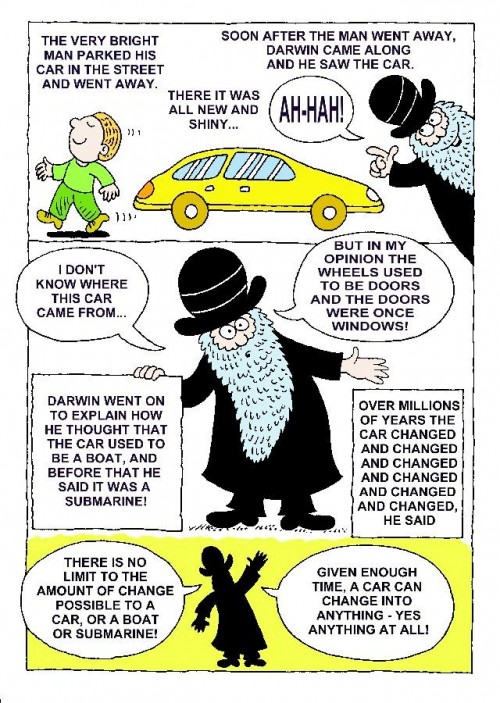

From 14 to 24, I didn’t encounter any skeptical or atheist literature. I argued vigorously with quite a number of creationists online, and thought that as an evolutionary biology student that I was pretty hot stuff. Until eventually some creationist (with more than the standard two neurons to rub together) claimed I was making up evolutionary just-so stories based on my authority and nothing else. And galling as it was, I had to admit it to myself. I had a provenance problem. But the bright side was that I looked at Creationists, and saw that their provenance problem was much worse and incurable. I could drop a few of my made-up arguments, limit myself to published science and identifying creationist fallacies, and I was fine.

One of the more noisome religious arguments I encountered was the accusation that science was due to pride, while religious believers were humble. I developed my own response based on provenance. Scientists, I would say, are the humble ones. Because not only must they restrict their claims to those based on evidence, but it must also be evidence that anyone else can confirm. The religious are the prideful ones: claiming that their prophets are the only ones with access to the truth. It’s a very common trick to accuse your opponent of your own sins, and thus one of the first we should expect from the religious.

Provenance also calls most philosophy into question. 99%+ of it is crap, for the simple reason that the provenance of its assumptions is unsupportable. A priori knowledge indeed! You don’t have to look far for “gut feelings” a la Steven Colbert. My favorite recent example of appeal to gut feelings is the first clause of the first sentence of the preface to Nozick’s “Anarchy, State, and Utopia”: “Individuals have rights….” That’s straight from his gut, an assumption of Natural Rights. He might as well be saying that individuals have souls for all the evidence he lacks. Some more modern philosophy, such as that of Daniel Dennett, does better by starting with reasoning based on the sciences, especially the biological sciences.

I used to think I was scientific and rational. Now that I know a little more about where my knowledge comes from, I know that I cannot depend on it without confirmation. When we start learning, we accept uncritically. After a while, we do start to test our knowledge for inconsistency and coherence with our own observations. But there is such a huge welter of knowledge that we cannot take the time to test it all, nor to re-derive it for ourselves. Imagine having to re-derive all the mathematics you learn in school. Mathematics that took the efforts of hundreds of mathematicians over thousands of years to create. So the vast majority of our knowledge is accepted on faith. What sense of “rational” is that? Rational turns out to be a Humpty-Dumpty word: it means whatever we want it to when we want to bash somebody else for not being rational. Is scientific any better? Maybe. Scientific provenance has to do with intersubjective confirmation of observations and how they match models or theories. At various times I have confused this with tribal loyalty to scientific knowledge. But very little of my life is actually concerned with doing science: usually I tend to use science as a censor for claims that I judge “unscientific”, such as homeopathy. Why do I trust science to be correct for such use? Not because I have confirmed all of the science I have learned, but because when ever I have tested scientific knowledge, it has stood the test of intersubjectivity. I have recapitulated the origins of the knowledge, the provenance, on occasion. So if I want to characterize myself as scientific or rational, it is at best relative to someone who is less so in a particular field.

Questioning the provenance of knowledge is perilous. After you discard the baby falsehoods such as gods and the rest of the supernatural and fictional crud, you quickly discover that pretty much everything else is also built on a foundation of sand. There is no ultimate truth or reality that we can’t question. We are left without even a foundation of sand: we are floating. What is left is reliable knowledge: knowledge that we can confirm intersubjectively, such as science. We can assemble that knowledge into a consilient raft without a foundation. That’s plenty to construct glorious social concepts of reality. We don’t need illusory anchors such as gods or religious beliefs: fictional whimseys can be enjoyable, but we don’t need to take them seriously to deal with the real world.

Mike Huben

United States