On Saturday, I wrote this bit about whether animals feel pain, and I said then I’d follow up that day or the next. I didn’t! I’ve been doped up on painkillers and my brain is all soft around the edges. I finally decided to give up on them this morning when I woke up, had breakfast, and then fell asleep for a couple of hours. Enough already. Now I have to recover from some potent drugs as well as my back pain.

Anyway, where were we? Oh, right, we had taken down William Lane Craig’s argument that humans (and maybe some other primates) are the only creatures on the planet that actually feel pain, that other animals are mere meat robots who act out a superficial script that looks like they are in pain, but really, they have no consciousness to experience the pain.

I don’t think he is making this argument to warrant or excuse animal torture, but rather he’s trying to justify human exceptionalism. See, humans have this special god-granted ability to perceive suffering and pain, which is why we have souls and animals don’t, and why we have to worry about that Final Judgment, since we can sense and appreciate the harm we do to others. At least, that’s my charitable assessment.

Curiously, in order to make this argument, Craig feels a need for some scientific backing, some recognizable neuroanatomical feature that shows humans are special. I don’t get it. He already believes in something invisible and intangible, the soul, so why not just say humans posess an invisible magical flimflam that the scientists can’t see or experiment on, neener neener, therefore humans are unique in having a conscience or ghost or pneuma that gives them the abilty to really truly deeply feel pain and suffering?

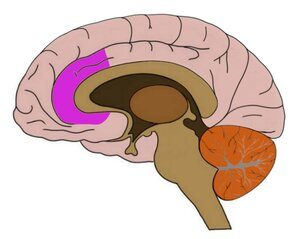

Often the physical substrate for feeling pain is determined in a backwards sort of way: we find some feature of the human brain that is only found in us, or is more pronounced in us, and we decide that, aha, that must be where this higher ability resides. Some of the common culprits are our enlarged pre-frontal cortex (PFC) or more narrowly, the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). The ACC was a favorite of Francis Crick, for instance, who thought that not only was it the seat of awareness, but also of free will (I think free will is a non-existent phenomenon that makes no sense, but I’ll defer on discussing that to another time).

Often the physical substrate for feeling pain is determined in a backwards sort of way: we find some feature of the human brain that is only found in us, or is more pronounced in us, and we decide that, aha, that must be where this higher ability resides. Some of the common culprits are our enlarged pre-frontal cortex (PFC) or more narrowly, the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). The ACC was a favorite of Francis Crick, for instance, who thought that not only was it the seat of awareness, but also of free will (I think free will is a non-existent phenomenon that makes no sense, but I’ll defer on discussing that to another time).

I don’t think the hypothesis is far out of line — there is evidence that lesions in this area do cause sensations of dissociation, and it is entangled in a lot of higher brain functions. But on the other hand, other animals have these structures, so how do you use this phenomenon to make humans exceptional? You can’t.

This leads me to an article in a journal called Philosophical Psychology, Against Neo-Cartesianism: Neurofunctional Resilience and Animal Pain by Halper et al.. Mixing philosophy with psychology and throwing in a lot of ethology and neuroscience sounds like a potent way to address the issue, don’t you think? Especially with a feisty abstract like this one:

ABSTRACT: Several influential philosophers and scientists have advanced a framework, often called Neo-Cartesianism (NC), according to which animal suffering is merely apparent. Drawing upon contemporary neuroscience and philosophy of mind, NeoCartesians challenge the mainstream position we shall call Evolutionary Continuity (EC), the view that humans are on a non-hierarchical continuum with other species and are thus not likely to be unique in consciously experiencing negative pain affect. We argue that some Neo-Cartesians have misconstrued the underlying science or tendentiously appropriated controversial views in the philosophy of mind. We discuss recent evidence that undermines the simple neuroanatomical structure-function correlation thesis that undergirds many Neo-Cartesian arguments, has an important bearing on the recent controversy over pain in fish, and puts the underlying epistemology framing the debate between NC and EC in a new light that strengthens the EC position.

In one corner, the Neo-Cartesians like William Lane Craig (there are also secular philosophers who like this idea).

In the other corner, the Evolutionary Continuity camp, which I would happily attach myself to, which argues for “a non-hierarchical continuum with other species and are thus not likely to be unique”. Yay Team EC!

The paper quickly dispatches part of the argument. All mammals have a prefrontal cortex, although the human PFC is relatively larger. So now you’re going to have to argue, if you think the PFC is the seat of awareness, that a quantitative difference leads to a qualitative change, and you’re also going to have the problem of a continuum of PFC sizes. Where do you draw the line?

Well, maybe it’s the anterior cingulate cortex, rather than the whole PFC, that matters. They have a case study that refutes that. Patient R is a man whose brain was devastated by herpes simplex encephalitis, yet survived with normal intelligence and anterograde amnesia (loss of the ability to form new memories). Most importantly to this point, he has retained full self-awareness.

Patient R, aka Roger (Philippi et al. 2012), provides us with a novel angle for assessing certain versions of the NC hypothesis. Roger has extensive damage to his PFC as well as his ACC and insula, bilaterally. He has been probed for self-awareness (SA) in numerous ways, some standard, some novel with positive results for all probes. The authors of the 2012 study concluded that SA is likely a function of the interaction of multiple brain regions, with some redundancy, rather than dependent upon one particular region.8 Roger’s case, like others described in the literature (Damasio et al. 2013), seems to demonstrate fairly conclusively that the PFC, the ACC, and the insula are not needed for SA, including SA of a fairly sophisticated sort, a sort we need not presume animals to have to make our case here.

Patient R also has a normal physical and emotional response to pain — if anything, he now reacts more strongly.

So now if you want to argue for a discrete localization of self-awareness in the brain, you’re either going to have to pick a different brain region or claim that Patient R is a p-zombie. Or, perhaps, that the brain has a lot more flexibility than was thought. I like this last idea, but then, that makes the pursuit of a feature unique to humans futile.

Further, these cases suggest an alternative to the rigid structure-function correlation thesis. Resilience of function following brain damage suggests the existence of degrees of freedom in the relationships between certain functions and neuroanatomical structures (Rudrauf, 2014). Anatomical regions and networks normally supporting central psychological functions (like the emotional appraisal of pain) may simply be the usual defaults. In patients such as Roger, functional resilience after such extensive and irreversible anatomical damage cannot be explained by structural plasticity, in the sense of anatomical restoration or large-scale “rewiring” (e.g., dendritic sprouting and axon regeneration) to restore structural connectivity. Large-scale functional networks supporting key psychological functions, however, can be maintained or restored even when the integrity of normal anatomical networks is massively and irremediably compromised.

This suggests that a different concept of flexibility is more apt, namely what Rudrauf (2014) has called “neurofunctional resilience”. This concept is based on the phenomenon of preserved function in spite of large-scale architectural changes, is not limited to one specific class of mechanisms or levels of observation, and indicates a relative openness in implementation at various levels of a functional hierarchy. The neurofunctional resilience framework, while in need of elaboration and refinement, makes more sense of lesion cases like Roger’s, observed variation in structure-function relationships in imaging studies, interspecific structure-function variations, the relative unimportance of lesion locales versus lesion size vis-à-vis functional deficits in the developing brain (Pascual, 2017, 5; Battro, 2000), and better fits general theoretical considerations about multiple realizability drawn from computational neuroscience. In realizing that a crude, “phrenological” localizationist structure-function paradigm (even one incorporating plasticity) is unable to account for these observable phenomena, one need not, of course, embrace the old holistic, “equipotentiality” theories of brain function (see Finger, 1994, ch., p. 4). A new, subtler approach is needed.

My first thought would have been that Patient R is an amazing example of neuronal plasticity, but the author is right: this is something more impressive. Big chunks of the brain are just gone; minor self-repair mechanisms, like neurons regrowing around a damaged pathway, are not sufficient. This is as if your car had the electronic engine timing system blown off, so the wires were rerouted to make use of circuits in your car radio instead. Be impressed! Brains seem to have a biological imperative to assemble themselves into some kind of cognitively functional structure, in spite of massive damage.

But never mind human brains — they’re too complicated, and you can’t do experiments on them. What about fish brains? Do they feel pain? And what about cephalopods?

As Godfrey-Smith (2016, 94 f.) notes, flexible behaviors and preference changes related to pain avoidance and analgesia-seeking (observed in both fish and chickens) in entirely evolutionarily novel situations and perhaps certain grooming and protecting behaviors associated with bodily damage are arguably best explained in terms of the presence of consciously experienced negative pain affect. And when one considers the overall behavioral, affective, and cognitive repertoire of, for example, cephalopods, as Godfrey-Smith does at length, the notion that such an animal, whose nervous system is so different from ours, does what it does in the absence of consciousness begins to look implausible and continued commitment to it perversely skeptical.

It seems more reasonable to follow the approach of Segner (2012, p. 78) who, in considering fish pain, looks at seven relevant properties: (1) nociceptors, (2) pain related brain structures homologous or analogous to those found in humans, (3) pathways connecting peripheral nociceptors to higher brain regions, (4) endogenous opioids and opioid receptors in the CNS, (5) analgesic-mediated reduction of response to noxious stimuli, (6) complex forms of learning, including avoidance learning of noxious stimuli, and (7) suspension of normal behavior in response to noxious stimuli. Humans and fish, Segner concludes, unequivocally share all but item (2), which is partially shared: we share subcortical structures with fish but not the neocortical structures. However, given the evidence reviewed in this section, it is clear that the neocortical structures commonly thought to be necessary for pain affect are not required in any case (cf., Merker, 2007; Ginsburg & Jablonka, 2019) Surely the other similarities are sufficient to make reasonable the inference to the presence of consciously felt fish pain (cf., Tye, 2017, 91ff.). For mammals, as we have seen, all of these similarities are in place.

That “phrenological” approach doesn’t work well for fish, and even less well for cephalopods which have virtually no homology with our brains. Those seven criteria are a useful rubric for figuring out if a given brain can be aware or feel pain, and like the authors say fish meet all of the criteria except #2, having homologous pain-related brain structures. But we also just saw that Patient R fails to have homologous pain related structures. It would be strange to then assert that an organism that has the other six features would have failed, in its evolutionary history, to have incorporated them into an integrated pain awareness system.

Segner codifies the basic analogy argument for the presence of negative affect in animals that goes beyond the one we all spontaneously draw from our admittedly fallible raw intuitions. On our view, this basic analogy argument coupled with the considerations about neurofunctional resilience (and evolutionary analogies) we have adduced yield a reasonably high probability for the claim that negative pain affect is present in mammals, avians, fish, and cephalopods. Even if we are mistaken about the latter three, however, these considerations make the claim that it is present in mammals so probable that the more ambitious NC thesis of M. Murray and W.L. Craig is cast into nearly insurmountable doubt.

The paper goes on to discuss in detail the specific question of whether fish feel pain (short answer: yes), cetaceans, the issue of blindsight, and much more briefly, consciousness, which would require a stack of books to consider. I’ll stop here, though, disappointed that nowhere does the paper discuss spider pain, or any invertebrates other than cephalopods. Invertebrates are so alien and distantly removed from us that it is nearly impossible to discern a pain affect in them, but they also meet 6 of the 7 Segner criteria. The pain pathways in vertebrate and invertebrate systems also show homology at the molecular level, and it’s possible to see similarites across many phyla.

Maybe that’s for a different day. I’ve been having a fun time lately diving into an area I’ve neglected for a while, developmental neuroscience, and maybe I’ll be motivated to tell you all why you should be kind to bugs, because they have feelings, too, and maybe even experience suffering.

If it’s neuroplasticity, you would expect less of a return in pain awareness following a lesion as the organism ages, so that might be one way to test it. You’d also expect a slow return in pain awareness following a lesion as neuroplasticity generally doesn’t happen immediately. But, when you consider how useful the ability to sense pain is (especially when you consider it’s ability to allow one to grow old enough to reproduce), you wouldn’t expect the brain to rely on only one mechanism. Also, considering pain is designed to make you stop doing (or avoid) whatever is causing it, whatever effect pain has could be considered suffering, regardless if us mammals would recognize it as such.

Experiences on the day job lead me to a belief that evangelical ilk

are able feign competence without actual/real/true creative thinking.

They’ve read the handbook & learned the jargon

I read a bit the other day on “creativity training”.

It was jargon-laden (an old family name)

and came to the conclusion that “obviously”,

this is most important to Business for Making Money.

Some of the jargon sounded pretty good, so I’m not tempted to argue with the promoters of Creativity Training Classes, but from my fringe position, it seemed like a good way to make money by rote learning of the proper spiel. Reading the article with my biased old brain made the whole thing looked like an advertisement: No need to be creative to teach creativity training, we have classes & you can buy the handbook.

I was hoping to find out how it was done in classrooms of kids.

My missus, the old teacher, says “just let them play”.

That’s hard to sell.

Nothing to add except that I like this analogy

Why can’t we say that we can perceive a living thing experiences pain based on its behavior alone? Attempts to escape a stimulus (especially one that is damaging a living being) indicate that it is reacting to what might be called “pain.” While a artichoke may not be able to experience existential dread, that it is producing spines is a reaction that might be an attempt to escape pain, or damage. If a creature is trying to avoid being eaten or damaged, it seems to me that it is suffering when its experiences those things it was trying to avoid. I see no reason why nerves or complexity or cognition are any more necessary than a soul.

It seems to me as though WLC would have been one of those good christians inspired by Descartes, who vivisected dogs and explained they didn’t feel it because they have no soul. I.e: wrong.

Because the philosophers have tainted our perception with all this stupid p-zombie stuff, just as they’ve taken all the joy out of trolley rides and vats full of brains.

There were also all those years of biologists going on about the perils of anthropomorphising, to (what seemed to me) an absurd degree.

There’s nothing an abstract concept hates as much as being anthropomorphized.

I also think you can argue that animals must perceive pain because a significant number are clearly self aware and seem to have empathy. When dogs play they immediately know to reduce biting to a level where they will not hurt you or the other dog. This means they know that the other dog can be hurt and don’t want to do so. Pack animals will protect and assist injured animals which means they understand what being hurt is.

…however, animals (especially mammals) are similar enough to people that it’s a question of empathy rather than anthropomorphizing.

Temple Grandin in her book Animals in Translation has a whole chapter on pain and suffering in animals. She states unequivocally that animals feel pain; read the book to see her justification for this conclusion.

She also says that animals can deal with pain a lot better than they can deal with fear, whereas in neurotypical humans it’s the other way around. She gives a number of examples where an animal was terrified enough in a single incident that the animal’s behavior was changed permanently. (Animal PTSD, I guess.)

It’s an interesting book…

Likewise, our cat. I’m pretty sure from her current behavior that humans terrified her as a kitten. There’s a lot of fear there that is easily brought to the surface.

Which is one reason we will be keeping her. We were originally supposed to just foster her until she was adopted, and we couldn’t bear the thought of putting her through that trauma again.

Allison@10

I’m not sure it’s the other way around for humans. People can put up with a lot from medical treatments as long as they trust the care provider, and there are not always effective ways to control the pain. Suppose someone put you through chemotherapy out of malice and no other reason? While it’s horrific enough for cancer patients, it would be an entirely different experience if you knew it was intended as torture and might also wonder if things could get worse. In fact, fear alone can be debilitating without any tangible consequence.

Watching Life at the Waterhole on PBS, the symbiotic relationship between ants and the whistling-thorn acacia came up. The tree provides a home for stinging ants that serve to protect it from browsers, but remove the browsers and the acacia essentially gives the ants the boot.

https://commonnaturalist.com/2014/03/03/ants-and-acacia-whistling-thorn-symbitoic-relationsip/

I’m inclined to accept that that’s purely mechanistic. There is a tendency to want to invest things with spirit, numen, intention, call it what you will. On the other hand, I think empathy has evolved as a reasonably good way of assessing the inner life of others, up to a point.

You gotta love those videos on YouTube of dogs reacting to Mufasa’s death in The Lion King. Like this one

I watched our beloved 16 year old cat suffering and screaming in pain a few weeks ago, until we could get him to the vet to be euthanized the next morning. Nothing can convince me that he wasn’t aware of the pain, and that our touch didn’t calm him.

Likewise, I could see how agitated the two girl cats were. The one who is half feral and much like PZ’s cat was hiding and trembling all night. Leia stayed very close to her buddy all night.

Both of the girls were agitated and off of their feed for a while as we all adjusted to him being missing from the house.

When my German Shepherd passed a few years ago, Leia grieved. She had grown up with him in her life, and even shared his dog bed with him. After he was gone, she would sit in the corner where his bed had been, glaring at me.

Nothing can convince me that animals don’t feel at least some empathy. My dog was a trained mobility dog, and he could sense my needs better than my husband can!

Humans and other animals evolved pain as a result of similar selection pressures- indeed, we inherited our pain-processing hardware from much more primitive organisms.

That alone should prove other animals experience pain pretty much the same way we do, without mucking about with discussions about qualia.

magistramarla @14: Our Max (big dog of uncertain ancestry) had a BFF Tarzan (husky), who was a wee puppy when they met, Max being a couple of years old at the time. For years, Tarzan’s human would walk him in the park behind our house off his leash, and Tarzan would often come by and sit with Max on our porch.

After Max died, I’d still see Tarzan now and then, and give him a scritch if he came close enough, but his appearances became less frequent. and age was obviously taking its toll when I did see him. One day, a few years after Max had gone, he was nearby when I was outside and I called out to him. He didn’t seem to recognize me right away, but then it clicked, and he lumbered over, tail wagging. I chatted with him for a while, and when I mentioned Max, he looked over at the porch and whimpered.

Yeah, they feel pain, they remember friends (and enemies!), they love, and they grieve.

Yeah, yeah. More self-justifying meat-eater bullshit from Marcus Ranum. “Pain” and “damage” are not equivalent terms: a wardrobe can be damaged; can it feel pain? A river can “react” to being blocked by carving a new path for itself – is it feeling despair at being denied its destiny of reaching the sea? Pain is an experience; what anatomical structures could possibly enable an artichoke to experience anything?

BTW – anyone else notice the parallels between Marcus Ranum’s “vegetable rights” rhetoric, and that of the forced birth brigade talking about the suffering of small clumps of cells when expelled from the uterus?

There are some people copying neuron collections and connections from honey bees and their flight and visual recognition capabilities far exceed humans attempt at trained networks in terms of number neurons and speed and power consumed. If we/they follow this route I think its almost certain that conciousness and pain will be found in something as small as a bee. I think conciousness is the product of movement – almost as soon as multicellular animals found an evolutionary benefit from moving there was some form of replication of the parts of the system of movement nerves that allowed abstract experimentation and learning and the concept of self, and soon after the concept of others so that very small animals could effectively compete, or co-operate in large groups of themselves and other species.

On free will. My feeling is that, similar to the way a neutrino can pass through mass from one end of the universe another largely unperturbed humans dont have free will. But in the same way we find walls solid the mechanism that makes us fell we have free will is so close to it that to pretend we dont is as useful as running as fast as possible into a wall.

Theologians need to stay in their Lane. It’s all well and good in the fantasy world, but as soon as they start talking about real word stuff, they need to sit down.

FWIW, plant communication.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plant_communication

Plants experience stress, but I couldn’t say what “experience” means for a plant. But maybe some day they’ll evolve into ents and explain it to us.

KG @ 18

It didn’t occur to me, but I did think of the very complex chemical behaviors occurring at the cellular level, which are kind of mind bending, at least for me, but which are nevertheless a far cry from needing palliative care when a reagents shelf life is about to expire.

I kind of like the idea in Avatar of all the living beings being able to plug into each other–sort of a conceptual antidote to seeing the world as disjointed and unconnected with humans as something apart, you know, as puffed up little demigods created in God’s image. In that sense I have no problem with feeling connected to plants and the rest of the environment; to the point that assigning legal personhood to the environment makes more sense to me than giving it to corporations.

It’s been decades since I read The Problem of Pain, but I’m pretty sure Lewis advanced some of the same arguments. It was clear that he was distressed by the problem of animal suffering, but never took it to the logical conclusion.

I honestly don’t see how there can be any doubt about it. Animals ACT exactly like human beings do when they are in pain. Scream, moan (or the equivalent), seek and take shelter, flee, seek protection and comfort… As someone above states, that really ought to settle the matter.

It’s even harder to explain away that some animals obviously exhibit empathy. In order to do that they need to be able to feel themselves what they see in others.

Isn’t it obvious we’re dealing with a psychopath here? Craig, like all apologists, starts with a conclusion and then looks for “evidence” to back it up.

That is, he’s already convinced of the old Cartesian (not even Neo-Cartesian, IMO) ideas about this and is simply looking for something vaguely science-y sounding to to hang his greasy flop-sweaty hat on.

Why does anyone give this sniveling plasticine mannequin the time of day anymore? He’s like Ted Cruz, only without the testosterone to grow facial hair.

I remember asking a friend if they thought that insects could feel pain. They replied that they could probably sense damage but not pain the way humans or other vertebrates do. I agreed at the time, but later found myself wondering if there was a meaningful difference between “sensing damage” and “feeling pain”. My guess is that any living thing with a nervous system (ie, most animals of any kind) can feel pain or something akin to it. Whether the actual experience of that pain is the same as for people is perhaps unanswerable, but since virtually all animals generally try to avoid pain and injury, my guess is that pain is a bad thing for all of them.

This may seem off topic, but maybe not. I spent much of my career as a systems engineer on a major satellite program, a $1billion satellite the size of a Greyhound bus and we launched them at the rate of one every year (they had a two year design life, but always lasted longer). The computer I am writing this on has seven connectors, each with about half a dozen signal leads for ~42 leads total. That satellite’s computer had 22 massive connectors with a total of 4,000 signal leads. Half of those leads were for sensing the status of various parts of various systems throughout the vehicle – temperature, position, pressure, voltage, etc. If any of these signals went out of a prescribed permissible range, the computer would put the satellite into one of four ‘safe modes’. Safe mode 1 was for minor problems that didn’t compromise the mission of the vehicle. Safe mode 4 was for major ‘Ouchies’ and the computer would lockdown the vehicle and send out the equivalent of a 911 call. When you work on a project like this it is inevitable that you anthropomorphize the beast. It was a she and we were intimately knowledgable about her anatomy. And yes, we did feel her pain when something (rarely) went amiss. If the mind of man or beast is really just electrochemical interactions, them feeling pain and suffering may not be that different for such machinery and mammals.

In case you think I am pushing this analogy way beyond any logical limit, let me note that this highly sophisticated object was the result of an evolutionary process, which was to a large extent a Darwinian evolutionary process with many guesses (what we called WAGs – wild ass guesses) as to best design decisions and a lot of trial and error. We never had failures, just what we called learning experiences. This evolutionary process also led to a high level of plasticity in the design – which we called redundancy: when a satellite was ready to give up the ghost (that is pushing the analogy too far) it would typically have a dozen or more failed components and subsystems, but would still be able to perform almost all its functions – a state I currently find myself in.

While on this topic (or off this topic) I’ll mention another intriguing analogy. When in the construction phase of a vehicle and we were ready to fabricate some component, we needed to get the drawing for that component. The responsible engineer would send an Expediter (we were a union shop) with the drawing number to the “vault’ to get a copy of the drawing. The drawings were kept in a literal bank type vault with two foot thick concrete and two inch thick hardened steel walls and a bank type lock on the door to protect against fire, earthquake, thievery, or whatever, since they represented hundreds of millions of $ of engineering, test results, meeting minutes, etc. The expediter would go to the counter in the vault where there were two technicians – two man rule: no single person ever alone in the vault. A technician would get the drawing and run it through a spirit duplicator to make a copy. No drawing ever left the vault. The drawing was taken to the machine shop where a machinist would send for the correct materials and make the part. The analogy:

Engineer = signalling molecule (e.g., a hormone)

Expediter = transcription factor

Vault = nucleus

Vault technician = operand

Drawing = DNA (yes, I am aware of the limits of this part of the analogy, but the drawings are an abstract representation of the component)

Spirit duplicator = RNA polymerase

Drawing copy (blueprint) = RNA

Machinist (and tools)= ribosome

Etc.

Perhaps it should be no surprise the the evolution of life forms, technology, language, and maybe some other processes should follow the same paradigm,

There is an evolutionary reason for pain. Look what happens to people who don’t feel pain. It’s there for a reason, and has nothing to do with suffering for gods.

I don’t know any harm caused by assuming that others experience pain, but there is plenty of gross and cruel history of assuming the opposite.

stroppy@21,

Yes, i’m well aware of plant communication. My router communicates with the internet. Does it feel pain?

Sorry, #29 was rather abrupt. The point is that the capactty for feeling pain requires specific anatomical structures and physiological processes, which will not have evolved unless there was a survival advantage to possessing them, and which are distinct from structures and processes for sensing damage, which many plants do have. The necessary “equipment” for feeling pain rather obviously hasn’t evolved in plants, any more than it’s been designed into routers.

KG @ 29, 30

Indeed!