Perhaps we need to think more about human psychology. There’s an interesting phenomenon that goes on all the time when people read about evolution: they shoehorn the observations into some functional purpose. There’s just something so satisfying to our minds to be able to say “that thing exists for this particular reason”, and we find it frustrating to say, “there is no reason for it, it’s just chance and circumstance”. It shouldn’t be so, but our minds just try to fit everything into that particular mold.

Now watch: some people — maybe even you — are going to now try and develop an adaptive scenario for why having brains that work that way is a good thing. We try to build a teleological framework around everything, and so it must have a purpose that is being fulfilled, and we rarely stop to think about whether it may be actually limiting us. Maybe it’s not good. Maybe there are other ways that brains can work, and this particular mode of thinking is just a clumsy kludge that resulted from the gradual agglomeration of stuff, mostly unselected, that built up the substrate for human cognition.

A case in point: the female orgasm. There’s a new paper out on the subject, and there are lots of articles being written on it, and they generally start out by pointing out that there’s something puzzling about the phenomenon: shouldn’t it have, you know, a reason for existence? It can’t just be, it has to do something useful for women, or reproduction, or pair bonding, or any of dozens of hypotheses that have been proposed.

So NPR finds closure in an explanation.

A pair of scientists have a new hypothesis about why the female orgasm exists: it might have something to do with releasing an egg to be fertilized.

Nope. That’s not what the paper says. It says it might be a relic of a historical endocrine function, not that it plays any role in women today.

Carl Zimmer sets up a mystery.

An eye is for seeing, a nose is for smelling. Many aspects of the human body have obvious purposes.

But some defy easy explanation. For biologists, few phenomena are as mysterious as the female orgasm.

I would challenge his analogy: what’s so obvious about a nose? Nostrils and an olfactory epithelium, sure — that does have a clear functional role, and we can see signs of selection in the signal transduction apparatus, but why do we have this bony projection with a knob of cartilage on the end? We think we’d look weird without it (like Voldemort), but there’s a wide range of shapes within our species, and related species — chimps and gorillas, for instance — don’t have much in the way of a nose. It doesn’t affect their ability to smell.

(Note: both of those links take you to good summaries. I’m just weirdly conscious of how much we all take adaptive thinking for granted.)

This is the point where I tell you all to go read The Case of the Female Orgasm: Bias in the Science of Evolution by Elisabeth Lloyd, in which she takes apart a collection of adaptive scenarios that simply do not hold up. We ought to face facts: orgasm in women has nothing at all to do with reproduction. It doesn’t facilitate transport of semen, it doesn’t make them want to lie down horizontally, it doesn’t compel them to pair bond with men (since masturbation is a more effective path to orgasm than intercourse, why aren’t we arguing that the clitoris is the devil’s tool to drive women away from men? Oh, some do.)

Fortunately, this new paper by Pavlicev and Wagner, The Evolutionary Origin of Female Orgasm, doesn’t succumb to the fallacy of the spurious adaptive explanation. Instead, it’s following a much more useful evolutionary tradition: everything is the way it is because of how it got that way. Every living thing has a line of ancestry, and we inherit with modification the traits of our lineage, and the necessary way to study these traits, since our ancestors aren’t generally available for examination, is to take a comparative approach. So they do the evolutionary biology thing and ask what functions female orgasm have in related species, and try to infer an ancestral role in pre-humans.

Here, we note that most hypotheses are seeking an explanation for the presence of female orgasm within the human or primate lineage, whether due to direct or correlated effects of selection. Yet we will argue below that female orgasm, as male orgasm, predate the primate lineage, and the orgasm of human females likely evolved from an ancestral and adaptive trait, which might not have all the characteristics of human orgasm and may also have had a different function. We propose that explanations focusing on primate mating system and behavior thus address the primate-specific (or sometimes human-specific) modifications of a previously existent trait rather than its origin (Amundson, 2008). Our focus here will be the question what that ancestral trait may have been. As the lineage-specific modifications or secondary cooption (“exaptation,” in terms of Gould and Vrba, 1982) can take extreme forms under different, internal, or external selective forces, we therefore do not expect to find in animals a female orgasm as we know it in human, but are rather seeking its homologue in other species.

They also place it in the context of more general theories about the basis of the female orgasm.

The field addressing the role of female orgasm is by no means short of hypotheses. The evolutionary hypotheses align in two groups: one group argues that it is not quite true that female orgasm has no effect on reproductive success (e.g., enabling female choice, bonding, etc.), and the other group argues that it may indeed have no reproductive value in the females, but rather its existence is explained as a correlated effect of another selected trait, or a different developmental stage. For example, one well appreciated among the later hypotheses describes female orgasm as a fortunate consequence of the shared developmental basis of clitoris and penis, and therefore a consequence of reproductive necessity of the male orgasm (by-product hypothesis, Symons, 1979). A critical review of the existing hypotheses has been published in Lloyd (2005) and will not be attempted here.

So the two general hypotheses are that it has an as-yet-undetermined reproductive function (this is so far unsupported by the evidence), or that it is a byproduct of other properties. Pavlicev and Wagner are, I think, adding some other nuances to the story, but their explanation is actually orthogonal to those two explanations.

Pavlicev and Wagner point out that induced ovulation is common in mammals, and is probably a basal trait of the clade, although it has been repeatedly gained and lost. It’s an energy saving measure; why should the female spontaneously ovulate all the time, in the absence of an opportunity to become pregnant? We take it for granted — nuns continue to menstruate, after all — but many mammals do not ovulate unless they receive an endocrine signal that announces to their ovaries that hey, you’re actually mating, this might be a good time to drop an egg for fertilization. In these species, the clitoris seems to be the trigger — stimulating it induces an endocrine surge that induces ovulation. So the idea is that humans have female orgasms because our distant mammalian ancestors had all this complex hormonal machinery coupling ovulation and coitus, and we’ve lost the necessity, but the apparatus is still there. We’ve dismantled the factory, but the remnants still make a fine playground.

Another interesting pattern they see is that when ovulation is uncoupled from clitoral stimulation, there is a tendency for the clitoris to waner farther from the vaginal opening. Induced ovulators tend to have the clitoris positioned right near or even within the vaginal opening, but in animals like humans, it’s quite far away and is poorly stimulated by vaginal thrusting. This may be another of those byproducts: the opening of the urethra happens to be between the vagina and the clitoris, so the increasing separation of the clitoris and vagina may be a consequence of increasing the separation of the urethra and vagina.

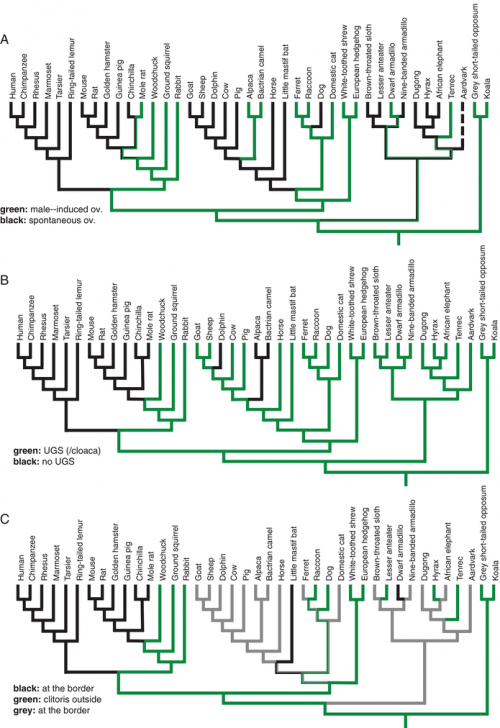

I do have some slight reservations about the paper, though. One is that the explanation is insufficient. Here’s their diagram of the phylogenetic distribution of induced ovulation.

Phylogenetic distribution of (A) modes of ovulation, (B) the presence of the urogenital sinus (UGS; in basal species: cloaca), and (C) the position of clitoris relative to the vaginal orifice (in, border, out). Note the phylogenetic correlation between spontaneous ovulation with the reduction of the urogenital sinus, and the external position of the clitoris. This correlation is suggestive of an ancestral role of clitoral stimulation for the initiation of pregnancy in induced ovulators and the loss of this function in spontaneous ovulators.

Note that our lineage seems to have lost this property at the separation of rodents and primates! One estimate is that this divergence occurred about 96 million years ago, so our ancestors had to have lost the requirement to link clitoral stimulation to reproduction deep in the Cretaceous, yet still maintained the association between clitoral stimulation and orgasm to the modern day.

That retention is still best explained by the byproduct hypothesis — the pleasure circuitry is maintained by ongoing selection for its operation in males, and there’s no purpose to untangling it and removing it from females, and in fact, selecting for anorgasmia in females might have unfortunate reproductive side effects in males.

I’d also suggest that it doesn’t answer another question: why does sex feel good? We have other urges that our physiology doesn’t address by inducing super-charged sensations — I mean, why don’t we have wild orgasms every time we urinate? Why doesn’t my thyroid send ripples of joy through my body when I balance my salt intake? If you’ve ever watched cats mating, you also know that sex for them is more a matter of compulsion than an opportunity to revel in pleasurable sensations by choice. Do salmon enjoy thrashing themselves to death? I might also argue that to some human males sex isn’t a matter so much of feeling good as it is conquest, expressing dominance, and flaunting their social potency to their peers, so there are clearly alternative mechanisms to make sure males mate with females.

I might suggest that the mystery isn’t the female orgasm, but the orgasm, period. But it’s only a mystery if you insist on demanding a direct adaptive explanation for its existence.

Let me just get this out of the way before I even read your article:

“What about the menz!?”

There’s not a single resource that’s contributed more to my understanding of how evolution works and the factors that need to be considered (and omitted) to perform good evolutionary analysis than Pharyngula.

Seriously, PZ.

Even other good sources (I’ll be reading Lloyd soon) are often ones I would never have picked up if not for Pharyngula.

Depth. Shape. Texture.

Though, PZ, you hold my attention because when you wander a bit away from your areas of specialization, you wander *toward* mine, this article is a perfect example of what I love most about your work.

I always thought it was to get them willing for sex, orgasm being the payoff, pregnancy being a side-effect that evolution exploited the relationship. Better orgasm, means more pregnancies, so more offspring. positive feedback loop.

just sharing my superficial first glance understanding. I doubt it severely actually as just cartoon biology.

Why has one of those TV shows never tackled this question?

I always just assumed it’s because men and women aren’t separate species and our bodies start out from the same template. Men orgasm, so women orgasm too because it’s not like the nerves and brain parts aren’t still there.

Without giving the issue much thought, this is kinda how I always assumed it worked.

That being said I have always wondered why we don’t have more orgasm-like drives. My initial thought would be that if we were having orgasms all over the place it would be difficult to focus on anything that didn’t cause orgasms (like society building, or bears). Anyway, interesting post.

“some people — maybe even you — are going to now try and develop an adaptive scenario for why having brains that work that way is a good thing. We try to build a teleological framework around everything, and so it must have a purpose that is being fulfilled, and we rarely stop to think about whether it may be actually limiting us. ” — Daniel Dennett’s “The Intentional Stance” does a really good job of both building the framework and stopping to think about its limitations.

@chigau:

how certain are you that Nimoy never tackled anyone before inducing orgasm? Did you ever see his last documentary?

This explanation has always seemed so obvious to me, though admittedly I’m a layman when it comes to evolutionary biology.

There’s evidence that the external structure of the nose is used for sound localization, your auditory perceptual system can use diffraction off it to help differentiate sounds from different directions.

The search term you want is “Head related transfer functions.”

Doesn’t it just make you more willing to have sex? What’s so inadequate about that for a “reason”?

Not only mammals have sex for pleasure. Birds continue mating even after oviproduction has ceased, masturbate too, and they don’t even have an organ that became the clitoral hood/penis. Surely that’s evidence enough that if it does something useful for the animal, it’s got to be useful for pretty much any animal. And the only thing useful for all animals in equal measure is getting the animals to mate more frequently.

CD #8

You make a compelling case.

Are you serious? I mean sure, eating yummy food or drinking delicious drink is different from orgasm, but there is no denying that it also induces pleasurable feelings. It is not true that “other urges” are not connected to the “pleasure circuitry”. Eating certainly is. If it were not, the whole cooking industry would not exist.

But sex can feel extremely good without ever having an orgasm (and most people with a clitoris don’t orgasm from penetrative sex) . Believe me, I conceived three times without ever having had a single orgasm (long story) and it’s not like I submitted grudgingly because it was the easiest way to have a baby.

Still doesn’t really address the question, because the important male function is ejaculation, not orgasm, and while they are normally closely linked, they’re not the same thing, and you don’t need to have one to have the other.

PZ did not assert that we have no other physiological urges which are connected to “pleasure circuitry”, just that we have some physiological urges which aren’t.

I was so close to solving this mystery a while back… the answer was right on the tip of my tongue…

The human-female reproductive evolutionary question which puzzles me more than this one has to do with the partial smoothing-out of hormone cycles such that women (unlike, sfaik, all other female mammals) do not have an overt estrous cycle.

Pop evo-psych writers (remember The Naked Ape?) decades ago spouted some awful nonsense (“women’s sexuality is always turned on to reinforce male investment” [not a verbatim quote, I think]), got duly shouted down, and wisely ran away. At least in my limited reading, nobody since has returned to the topic.

I’ve played with a hypothesis that, among early anthropoids, those females less hormonally overwhelmed exercised greater choice in mate selection, thus influencing evolution in significant ways – but I lack both training and evidence, so can’t even shape that up into a worthwhile mental toy.

Can anybody steer me towards informed, layperson-accessible, readings on this question?

I’m definitely leaning towards the byproduct hypothesis, in which case the orgasm itself could just be a happy accident – it developed out of genetic drift or by something else, and then was never sufficiently selected against to remove it.

Hell, anything that makes humans more likely to breed would be readily retained. Humans are slow-breeding and slow to reach sexual maturity even by placental mammal standards. The only mammalian megafauna that breed even slower and have a similarly long development period before sexual maturity are, what, whales and elephants?

The byproduct hypothesis does seem the most likely, but whatever the cause for the existence of female (and male) orgasms, not to mention sex in the broader sense, I think most of us are just really, really glad the biological chips fell the way they did.

Some things are just a mystery right now. As for why we have this sticky-out nose while most primates do not, I offer the hypothesis that it has no purpose per se, but is a side effect of reduction of our facial bones. Our face shrank but the bony area around our nose did not shrink much.

Now comes the question: why did our face shrink? I dunno.

If you’ve ever seen a closeup of the male cat’s glans, you’ll realize that feline sex fucking sucks (for the female), although:

this is another example I have read here of understanding evolution that is not what is generally understood. I think it does follow the thinking behind Darwin’s original insight the insight that really is at root of any controversy about evolution spawned.

For me it, this post, re-enforces the idea of purposelessness in evolution and by extension the universe. We are such little things in all this vastness and still seem to want to see the things around us as well as ourselves as having meaning. We have this ability to see patterns which is a good and useful ability. It is helpful for our ability to predict events from past observations, but we still like little kids tend to see everything in terms of ourselves. To see things as they really are is humbling.

From that humility can come true understanding and wisdom which are a prerequisite to correct and effective action.

uncle frogy

But that doesn’t change the fact that it’s not the mystery of the female orgasm but the mystery of the human orgasm.

#19: Could be better. Just imagine if you had an orgasm every time you had to pee!

@marcoli #20:

An advantage for speech is the first thing which comes to mind.

Note that I present no evidence.

Speak for yourself, prude.

Everything about human sexuality is odd except the male role. Women have breasts which can also be stimulated to orgasm, in addition to menses rather than estrus, and sex rather than seasonal mating. I’ve never understood why anyone would consider female orgasm an oddity, if women didn’t find sex pleasurable enough to seek a mate we wouldn’t do much evolving. Like nipples, the basic template for human nervous system has built in pleasure circuits, and everybody gets them though they might be wired up a little differently.

Did our face shrink, or did the rest of our head grow? Noses vary quite a bit in humans. Our brains have grown enormously, while at the same time our jaws, teeth, and the heavy skull structure necessary to support that musculature has shrunk. I would guess that fire and cooking our food and a bit of sexual selection is the cause of that. Most humans still have the third molar, even though most humans don’t have a jaw big enough to accommodate three molars.

one of the things I msut watch out for is this idea that there is one answer to everything. from experience and observation there seldom exist one solitary answer outside of an exam question that suffices. Everything seems to be a mixture to put it mildly.

when thinking about our facial structure and why the apes don’t have noses the stick out I thought immediately of this guy https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proboscis_monkey

while not an ape he is a primate and sure does possess a notable schnozzola. and the idea of sexual selection as mentioned above not something to be ignored in thinking about beast that does seen to expend an awful lot of energy to sex and sexual attractiveness and sexual activity.

uncle frogy

What about multiple orgasms? They are not only limited to women, yanno. I had three orgasms in a row, just last year – one in June, one in July and one in August.

@PZ

<blockquotrwhat’s so obvious about a nose? Nostrils and an olfactory epithelium, sure — that does have a clear functional role…but why do we have this bony projection with a knob of cartilage on the end?

Synchronicity! Just this morning I came across an article in the Annals of Improbable Research discussing a paper with a hypothesis on that very question:

http://www.improbable.com/2016/08/01/the-purpose-of-the-prominent-human-external-nose-a-theory/

Eegh. Sorry about the blockquote fail.

PZ Myers @ 24;

That could be… actually rather inconvenient, come to think of it.

And it could also be one heck of a lot worse than it is. The notion of barbed penises of the type cats are afflicted with is one of the most horrifying things I can easily imagine, for both men and women.