Bringing extinct animals back to life is big news this week. Not because there’ve been any particular recent breakthroughs, but because the upcoming issue of National Geographic features the topic as a cover story, and is hosting a related TEDx meeting this Friday in Washington D.C. that’s also sponsored by Stewart Brand’s Long Now Foundation. There’s a Twitter hashtag for the meetup, National Geographic has set up a portal page for the topic (credit Brian Switek for that labor), and the event is driving a lot of traffic to the Long Now site — which is worth checking out, especially its FAQ and its list of criteria for choosing extinct animals to bring back.

But I see no mention of bringing back the extinct animal we actually really need.

Here’s a teaser for the conference via NatGeo:

Bringing back extinct species is a controversial topic, and for a number of good reasons. Once a species goes extinct the relationships individuals of that species had with other species also go extinct, and the ecosystems in which the vanished species once lived change. Sometimes that change is radical. Long Now points out the extinction of the Mammoth Steppe environment that went along with the extinction of the mammoth, as boreal forests grew up without elephants to trample them.

Sometimes the change might be barely noticeable. If a particular species of bee and a particular species of annual plant have an exclusive pollination relationship, one of them going extinct might cause the other species to die out as well, but with little overall effect on the ecosystem that surrounds them, with local animals having one less flavor of bug or plant to eat but otherwise carrying on unaffected. Regardless, the ecosystems an extinct species might have lived in generally don’t sit around being stable once one of their components is gone. They move in a new direction and become, to extents major or minor, new ecosystems. No one’s really talking about reviving vanished species so that we can keep them in zoos or research labs forever: eventually, we’ll be considering whether to release them. But where do we release them? North America has had 8-12,000 years to adapt to the loss of its megafauna: reintroducing the woolly mammoth into its former geographic haunts could be seen as releasing a potentially destructive invasive species into a habitat that has long since moved on. Far from helping heal ancient damage, such a reintroduction might well cause even more new damage.

Another complicating factor is that organisms, as my co-blogger here has pointed out on several occasions, are more than their genome. This is especially true of some animals. The larger a brain an animal has, the more likely it is to have something like culture. This became important when the California condor went extinct in the wild. Pre-breeding-program California condors taught their young how to behave in the wild — how to approach food, how to avoid danger, things like that. Condor culture was passed down from generation to generation. When condor biologists captured the last wild condors in the mid-1980s to enlist them into the so-far successful captive breeding and reintroduction program, they had to play close attention to that condor culture. They’ve done probably as good a job of maintaining that culture as they can, feeding chicks with condor puppets and such, but there are inevitable changes to that culture as a result of human interference.

If the extinct Teratornis merriami had a culture anything like the condor’s, are we really reviving the teratorn when we clone it from some old DNA and hatch it under, say, a condor host mother? Or are we really making a zombie Teratornis that possesses the physiognomy of its extinct kin but is otherwise as blank a slate as its genome allows?

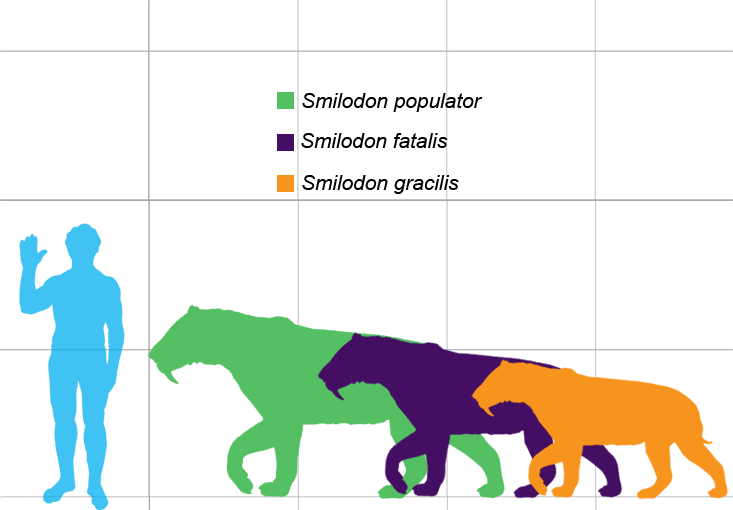

Lastly, even if we do have patches of intact habitat left that more or less fits the candidate, what threats do our continued activities on the planet pose? Look how much trouble we’ve had reintroducing the gray wolf to the contiguous United States. The gray wolf isn’t even extinct, and there are at least hundreds of Americans who wish it was, and they have guns and generally low levels of environmental ethics. Long Now lists Smilodon as a potential candidate for re-animation, presumably to keep the reintroduced mastodons and mammoths from getting out of hand. Smilodons of various species roamed what are now the Southwestern United States, including much of the area where violent “shoot, shovel and shut up” opposition to wolf reintroduction is rampant, and we’re talking about setting these loose among the yahoos:

I foresee some potential public reluctance here.

The thylacine is also mentioned as a candidate for reintroduction, but the forces that pushed the thylacine to extinction — loss of the emu as a food source, habitat disruption in Tasmania, and that island’s equivalent of Arizonan yahoos with guns and loose morals — are still very much a factor. The California Condor, which is the closest thing to a reintroduced extinct animal we have, still suffers from the things that worried the biologists — poisoning from lead shot, power line hazards, and sociopathic plinkers among them, and now we’re building gigantic wind turbines in the habitat into which reintroduced condors seem to be expanding.

So, lots of problems. An ideal candidate for reintroduction from extinction would therefore need to possess a few attributes:

- The species would need offer the potential to fit into an ecosystem without damaging it, potentially filling a role without which that ecosystem is suffering.

- The species would need relatively unchanged habitat that’s protected by law, and the bigger the species the more acreage it’ll need.

- The species would need to offer a diverse source of extant DNA.

- The species would need to be valuable for behavior that it would either do by instinct or in which we could train it ourselves.

- The species would need to pose limited potential threat to humans, and should ideally offer some benefit to provide incentive that sways opponents.

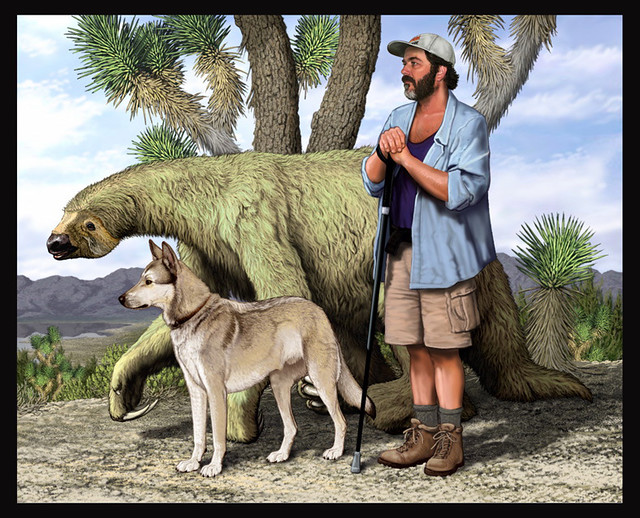

Gentlewomen and -men, I propose to you that we adopt the Shasta ground sloth as a primary candidate for reintroduction from extinction.

I’ve written about the Shasta ground sloth (Nothrotheriops shastensis) before. I live in an ecosystem that once hosted Shasta ground sloths, and that ecosystem is suffering for their absence. The sloth’s extinction has even made the news. As I wrote in 2006, after studies that indicated the Joshua tree (Yucca brevifolia) might be on its way to extinction as our warming climate makes the trees’ current habitat too warm for them, and the trees fail to get their offspring to more amenable places:

The problem is seed dispersal. Joshua trees don’t do it well. Oh, ladder-backed woodpeckers will hammer at fallen fruit to get the worms that live inside, thereby spilling seeds all over, and packrats will pick up seeds and fruit and carry them fifty feet from the tree or so, and there are a few other birds and rodents that play a role in moving Joshua tree seeds around. Every once in a while, a coyote might eat a fruit and shit it out ten miles away. But unless the tree is on a long, steep hill, its golf-ball-sized fruit tend to stay within a few meters of the parent tree. The seeds are large, and seem to have no adaptations allowing birds to carry them long distances by accident: no sticky burrs, no sweet pulp surrounding a gut-proof seed coat, nothing but a delicate little black flake. Most of the time when something eats a Joshua tree seed, it kills the seed.

… Joshua trees are tall, heavily defended plants with fleshy fruit growing at the top, sometimes thirty feet off the ground. There are quite a few plants in the Americas that, like the Joshua tree, seem ill-adapted to seed dispersal because their fruit isn’t designed for any living animal to disperse efficiently: the Osage orange, the pawpaw, the avocado. Many of these plants have been linked to the giant extinct animals of the Pleistocene, big critters who could denude a pawpaw or avocado tree of all its fruit, walk a ways and excrete the tree seeds, seasoned only slightly by digestive juices. Could Joshua trees be another such plant, dependent for seed dispersal on an animal species that will never come back?

Nothrotheriops shastense… lived throughout the range of the Joshua tree in the Pleistocene, up until about 12,000 years ago. That’s recent enough that you can still find its mummified dung in caves in the southwest. Said dung has often been found to contain the remains of Joshua tree fruit, with seeds that likely would have been viable when excreted.

Nothrotheriops‘ powerful arms and huge claws, shown above in Carl’s painting, were certainly adequate to bend Joshua tree limbs downward so that the animal could bite off an entire cluster of Joshua tree seed pods and swallow them whole. The animal could then, even at a sloth’s pace, move those seeds several miles before depositing them on the landscape in a nice matrix of moisture and fertilizer. If Nothro’s digestive habits were anything like those of some of its living relatives, those seed pods might have taken a month to make their way through the sloth, which is plenty of time to be carried across a couple of state lines. If we still had the sloths around, there’d be nothing keeping forests of Joshua trees from following the climate northward as it warms. There are mature cultivated Joshua trees thriving in spots a hundred miles north of the tree’s current wild range: if we had sloths, there might be forests of those Joshua trees filling all the appropriate places in between.

And we’re not just talking about a single tree species here that’s at risk of going extinct for lack of sloths. For one thing, there may be two species of Joshua trees. There are certainly two species of moth that utterly rely on the Joshua tree for its own survival. There’s the smallest lizard in North America, which relies on fallen Joshua tree limbs for the bulk of its habitat. Ladderback woodpeckers hollow out holes in Joshua tree trunks for homes. Loggerhead shrikes use the leaves’ terminal spines as kitchen utensils, impaling their small prey for easier eating. The yucca-giant-skipper uses the tree’s trunks as habitat by boring into a leaf bud. That kills the bud and some of the stem, but in a healthy tree that’s not much problem — it can actually spur branching and subsequent greater flowering.

The trees provide a food source either directly or indirectly for dozens of desert species, from the desert woodrats who use the leaves as a readily available snack and source of metabolic water, to the ground squirrels and birds who eat the seeds and the developing yucca moth larvae, to the cottontails and jackrabbits who predate on the majority of Joshua tree seedlings. Termites eat the dead and dying trunks, native fungi inhabit the layer beneath the bark where a dicotyledonous tree would have cambium, side-blotched lizards gorge on the annual orgy of dying male yucca moths. Without the trees some of those species would do okay: loggerhead shrikes seem perfectly happy to impale their meals on barbed wire, for instance. But it’s not too far off the mark to refer to the trees as a keystone species for the Mojave Desert upland ecosystem.

And without the Shasta ground sloth, that ecosystem will likely disappear in the next 150 years.

Due to the ground sloth’s habit of picking favorite desert caves and shitting abundantly therein, we’ve no lack of potential sources of DNA. We’d have to be creative about gestation: while one could conceivably clone a mammoth with an Asian elephant acting as incubator or a Smilodon with a female big cat with little harm to the dam, Nothrotheriops’ closest living relatives are quite a bit smaller. Unless we find a way of fooling a large animal into gestating ground sloths for us, we’d have to develop some sort of in vitro gestation. That would take time, many likely failures, and investors committed to reaping potential side-benefit rewards, but we’ve got about a century to figure it out.

Once we have the sloths, where do we put them? The Mojave Desert is one of the least-developed and most-protected of the North American habitats that Pleistocene megafauna wandered; there’s plenty of places for the ground sloth to roam. They eat plenty of other things besides Joshua tree fruit, which is a good thing and a potential problem both. Through analysis of sloth coprolites — remember those caves full of ancient poo? — we know that sloths also ate agaves, ephedra, shadscale, acacia, mesquite, cacti and various annual plants.

Releasing pony-sized ground sloths weighing about 400 pounds out to eat the desert’s foliage will likely earn some opposition from people worried about the effect of grazing pressure on wildlands. There’s an easy answer to that: reduce that pressure from other directions. The U.S. government currently subsidizes desert grazing by non-native cattle to an absurd degree: a permit to graze a steer, or a cow and calf, on public lands currently costs ranchers $1.35 a month. The damage to the desert’s vegetation and watercourses is considerable, and the suffering the cattle go through even before they’re trucked off to the slaughterhouse is mind-bending.

Why not replace desert cattle grazing with ground sloth wrangling?

Public land cattle grazing produces a completely insignificant percentage of the country’s beef, something like one or two percent last I checked. Subsidizing it is essentially a way to preserve a core rural constituency’s lifestyle on the public dime. Why not put that government subsidy to a better, higher use? Once we get a breeding population of Nothrotheriops put together — which, I know, is easy for me to say — we offer willing ranchers a chance to get to know how to interact with them. I’m thinking they’d have to be easier than cattle: less than half the size, much slower, capable of doing serious injury but probably not more so than an angry bull.

And then we make it legal to sell sloth meat. Their extinction almost certainly stems from the fact that they were good to eat, after all. Put them out on the desert range, let the ranchers build the sloth populations up to a viable point, and then start culling a few males from each generation for sale as meat animals.

As I see it, this would:

- Neutralize a core group opposed to reintroduction of species by giving some of them a chance to profit from it, which will prompt them to take measures to protect their stock;

- Outsource the continuing research on sloth habits and consequences of reintroduction to industry;

- Seriously ease pressure on the desert’s watercourses by replacing cattle with a species more adapted to arid lands;

- Provide a new, potentially sustainable source of meat for ecologically concerned carnivores, not to mention members of the Slow Food movement;

- Increase the chances for survival of the Joshua tree and its attendant species by allowing the Mojave Desert upland ecosystem to migrate as far north as it can, under the watchful eye of the slothherd.

And yet if you search for Nothrotheriops on the website of Revive and Restore, The Long Now Foundation’s de-extinction project, you come up with nothing. That seems short-sighted of the Long Now, if you ask me.

Wonderful.

At last I know what I want to be when I grow up: a slothherd.

Great idea.

We cold also toss the occasional sloth carcass to the condors.

And they eat mesquite trees? Really?

Do you have any idea how popular that could make them in West Texas?!?

As far as the Thylacine goes, habitat destruction and random shooting played much less of a part than organized extermination. There was a bounty on the Thylacine for decades, and it’s pelt was considered useful – by the time it was realized the campaign was a little too sucessful, it was too late, and the Thylacine population had dropped below it’s capacity for replacement.

So how big would a uterine replicator* for a baby Nothrotheriops need to be – 2 or 3 times as big as for a human? It might be easier to design / build one than find an adequate host mother species.

*See Lois McMaster Bujold’s book “Barrayar,” among others.

The O’o was aptly named. I propose we change our name to Homo Oops.

Some ground sloth (not sure of the species) or at least some other very large herbivore seems to be essential to Central American tropical dry forest too. So there’s another candidate.

I would consider the revival of Nothrotheriops as a feasibility study for the revival of Megalonyx jeffersonii.

Are they friendly? They must be friendly if they were driven extinct so easily. Maybe they make good pets? We could make a merchandise driven cartoon about them, which would be awesome because ground sloths are way cooler than ponies anyway.

Haast’s Eagle, on the grounds that it is Totes Wicked Awesome.

Probably not so much ‘friendly’ as ‘slow as hell’.

I bet they stank, too.

Stank? Not with enough barbecue sauce.

But the easy extinction is a sad recurring tale that sometimes involves species being more placid than they should around unfamiliar H. sapiens. Might’ve gone down like that. I’ve heard that’s how it was with Dodos.

We oughtta get this sort of project in high gear! New (to us) frog species are going extinct as quickly as they are being discovered. Culture probably isn’t an issue for most frogs and gestation isn’t either. That makes them great candidates for a Lazarus treatment. Bust a move, science boys! Yeah!

(/ignorant as Dubya but means well)

Oh, and stank can be pretty good protection for a species. Notice hoatzins Least Concerning all over the place. So maybe they weren’t any jankier than a goat? Damn I’d love to see something like this. *sigh*

-The aurochs would be easy to incubate inside a cow.

How about the giant birds in New Zealand? And maybe there are enough bones left in sinkholes on the nullarbor plain to get useful DNA from the lost Australian megafauna, from 50.000 years ago.

The cave bear, being an omnivore, would not necessarily be more of a hassle than a grizzly.

Heh. Slow Food movement. Heh. Heh heh heh.

Thank you for this article, Chris. I knew sloths were useful for more than just generally laying about.

What’s all this worry about culture? I saw A.I. and it showed you can clone an entire woman, her memories, and even her age, from a single hair!

Can we reintroduce Sabertooth tigers and equip them with kevlar vests to put some selection pressure on the human gene pool? We could use it.

“Hey, hold my beer and watch this” is not effective enough to have a positive effect, due to it usually occurring after breeding age.

>”*See Lois McMaster Bujold’s book…”

I approve of this fandom.

Yes. Definitly. Bring back the Thylacine.

Any idea the required ranger per ground sloth?* And how many would need to exist for a stable breeding population? Maybe we could convince them to live on golf courses and in housing subdivisions in what used to be large swaths of the desert?

* Sorry. As I was typing that, I flashed on, “I wonder what the market would be for sausage made out of sloth?”

If only we could “clone” a horse size dinosaur. Conservative Christians could ride them all day, flintstone style, as tears well up in their eyes – ah the good old days are here again.

Dunno. How many rangers do they eat per week?

Whilst rangers are inexpensive, the supply is limited, so we’d need to find some other suitable diet — or, as suggested above, train them to not be quite so picky about which long pigs they eat. Could they eat peas and(? or?) horses and thrive? That’d solve several issues at once…

oops. blockqoute fail, sorry.

Depends on the size of the ranger. Addtionally, I thought ground sloths were vegetarian.

Well, the supply of rangers is dwindling quickly (because we are too expensive (no, I do not kid)) and the number of vegetarian rangers is small to begin with.

Moderate Republicans? In Latin? That would be the elusive Mythicon entia.

Does this mean there’s some hope for the Principled, Reasonable Conservative?

(Or was that always a cryptid?)

If we bring back the Shasta ground sloth, can we also bring back the Royal Crown ground sloth?

/this joke is soda pressing

//ba-dum-chaaaaaaaa

A sloth, by definition, is the very embodiment of a Deadly Sin™.

Isn’t it bad enough to have gluttons still rambling around Europe and Canadia?

Will you sinful atheists never stop until we have prides and lusts and covetousnesses lurking behind every corner to tempt our innocent children?!?

Well, the miniature Nehi sloth was saved from extinction, right?

There’s a bunch of poisonous ground berries in the redwoods that also don’t have a method for transporting their seeds. Right now they mostly roll or float to a new location, but they have no way to get to the top of another hill. Nothing currently living in the forest can (or should) eat their offerings of purple berries.

Maybe I don’t read enough extinction reversal essays, but that was probably the best argument I’ve seen. I had no idea there were ecosystems still reeling from animals extinct thousands of years ago, but it makes sense.

indeed. There is some evidence to suggest a similar case to that Chris made for the giant sloth can be made for Moas in NZ; with limited support for the idea that some species of plants depended heavily on Moas.

I can’t say for sure though… all the more reason to bring them back so we can find out!

:)

oh, and before I forget, shame again, on Nat Geo for using the asinine “ARE WE PLAYING GOD?” headline for that article.

just mindbogglingly stupid.

Great post Mr. Clarke.

I liked all of this post until you got to the part about eating the poor sloths. :( Don’t eat them! Let them roam free!

But I love the idea of reintroducing them. They are ADORABLE. (Sloths are the best. Someday I hope to visit the sloth sanctuary in Costa Rica.)

Re Thylacine: no reason we can’t put the emu back in Tasmania; mainland emu is only 10Ka separated from the extinct island subspecies, which is probably a better match genetically than a reconstructed thylacine would be. Tasmania’s kinda small though, as we’re seeing with Devils now (and apparently with human culture; various bits of mainland technology are thought to have been lost through cultural accidents, including boats, fishing, and firemaking). So we need disease-free devils on the mainland (and New Guinea, why not? – they were there not long ago) and thylacines too, when we can make’em.

Unfortunately, Australia’s warm climate is very poor at preserving DNA outside of living organisms; I think that most of the genetic material of thylacines has been recovered from specimens kept in Europe and North America. The Nullarbor caves were a total bust from that angle; so while Australia has a world-class ancient DNA lab and research group in Adelaide, they work mainly on material from elsewhere. I’d have thought that parts of Tasmania should be comparable to New Zealand for DNA preservation though; maybe we can pick up some Diprotodon after all, which are about as dorky-looking as ground sloths and would make equally good rangeland livestock.

Slow food: take a number now, and wait for your double bacon slothburger.

The idea would be to let them roam free, live full and slothful lives, then eat some. This would be the source of income that will allow the rest of them to keep roaming free.

These are the kinds of things that serious, science-based wildlife conservationists have to think about all the time. “Adorable” might influence the decision to try the project, but it will have exactly zero to do with actually making it work.

hear hear!

there simply has NOT been enough mention of bacon around these parts of late.

Trivial, but since I live in view of Mt. Shasta and vote for the Shasta County sheriff, I am curious: Any idea why this creature of the (Ice Age) desert Southwest is named for a NorCal mountain?

It wasn’t limited to the American Southwest- it ranged up into Northern California, Oregon, and even Alberta.

It’s not generally understood that the present California desert was very different only 20,000 years ago. Before the long (and maybe continuing) dry-out, there were huge lakes and rivers; Joshua trees coexisting with juniper and pinyon pines and mequite trees and all kinds of herbaceous vegetation to eat. Present-day creosote flats had nary a creosote bush. (We know much of this thanks to ground-sloth dung, as well as fossilized packrat middens). Sabertooths hunted ground sloths and [pre]desert tortoises hung out with Western pond turtles.

I don’t know how different the rest of the range of the SGS was back then. They were probably pretty habitat-general; as hindgut fermenters any old vegetation would do.