I recently watched an old French film with English subtitles. But the timing was very slightly off in that the English words appeared a beat or two after they were spoken. If there were gaps in the dialogue, then one could keep the recently disappeared video image in mind while waiting for the translation to appear. But in quick exchanges, the words that one character spoke would appear when the other person was responding. It was extraordinary how this very slight time lag made it very difficult to follow. My brain found it very difficult to make the rapid adjustments necessary to restore continuity.

I have been similarly disconcerted even when no subtitles are involved but the audio track is slightly misaligned with the video, so that the words and the lip movements of the speaker do not match. Even the slightest difference is very off-putting, which shows how much our brains are conditioned to expect lips and sound to be synchronized and finds it hard to accommodate even slight amounts of asynchrony.

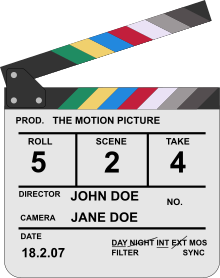

I used to wonder what the purpose of the clapperboard was that I am sure everyone has seen, where during filming someone claps the top down and says ‘action’ to begin filming a scene. It is apparently to enable the film editors to align the sound with the video by exactly matching the sound of the ‘clap’ with the visual. But it looks like even with that system in place, older films can experience misalignment later.

I used to wonder what the purpose of the clapperboard was that I am sure everyone has seen, where during filming someone claps the top down and says ‘action’ to begin filming a scene. It is apparently to enable the film editors to align the sound with the video by exactly matching the sound of the ‘clap’ with the visual. But it looks like even with that system in place, older films can experience misalignment later.

I used to have that trouble with a device of mine. When I was watching something on Netflix or Amazon Prime, the audio and video would drift apart just enough to be disconcerting. I had to jump to home screen and start navigating back to the video in order to sync the audio again. A recent firmware update seems to have fixed it, thankfully.

This is a bigger issue now than in the past. With film, the audio track (or tracks) was physically part of the film itself. The relation between the audio and image was fixed and standardized. Similarly, the audio track of a video tape was on the same piece of magnetic tape.

But this has been compromised with digital media. All digital formats are compressed, which means that computers are used to decompress the data. The video and audio generally use separate compression methods so each decompression stream can take different amounts of time, and each is dependent on the hardware (computer processor speed) and algorithm implementation.

The audio has to undergo further processing in a digital-to-analog converter, again with a device-dependent time delay. On digital TVs there’s no video D/A conversion per se, but there can be delays associated with transferring the image data to the actual display panel.

These can add up to a noticeable desynchronization between the video and audio. The processors implement delays and buffers (as needed) to ensure the two streams end up in sync, but these don’t always work exactly right. Most TVs have settings for auto syncing or other adjustments that attempt to minimize the issue, with varying effectiveness. I have found that the problem can also be dependent on the source material or even occur on one particular TV channel while the others are fine.

It could just be bad editing but the two languages are not likely to have the same amount of time per sentence. I know in the two written languages, we typically had to assume 20 precent more reading time in French than English as English seems to be a more curt language.

This type of thing is really apparent watching a Mandarin language movie dubbed into Cantonese. Mouth movements lose all connection to the audible speech. Of course, that I speak neither Mandarin or Cantonese may have magnified the effect. It still was strange.

Exactly where the lag was introduced in the source you is possibly numerous -- the source was a digital file that wrapped, probably, at least three streams of data: the video, the sound and the subtitles.

If it was originally one recorded at 23.76 frames per second (as film generally was shot) but is now broadcast/streamed at exactly 24fps, or 30fps or 60fps or… synchronisation issues can easily creep in.

Subtitles usually specify when they appear in units of time, not frames. so that the frame rate doesn’t effect their showing -- but if changes in frame rate aren’t handled properly it changes the timing of what appears.

Or cropping of a movie -- perhaps a fraction of second trimmed from the start (as some licensed credit, black space or logo is removed) without thinking to alter the time codes in subtitles can screw it up.

While most media players let you easily adjust the timimg of audio to correct synchronization problems it’s not so common for them allow easily adjusting subtitle problems.

This article helped me with a similar issue, I started watching the first episode of “Black Spot” the other day, but found the dubbed English too annoying to stick with it. Then after reading this I switched the audio to the original French and displayed English subtitles. It’s still not my usual genre of choice, but I do find it a lot more engaging now (enough to have finished that first episode anyway).

Some years ago I was involved in developing the firmware for an AVoD (Audio / Visual on Demand) service, not the AVoD specifically, but the core chip and operating system. The AVoD experts’s guiding principle was simple: “Audio. Audio. Audio.” Human hearing is vastly more sensitive than the human vision, and things like occasional varying audio rates, dropped audio samples, and so on are much more likely to be detected than the occasional video equivalent. The guideline was “the speakers are in control”; the way to view the system is to imagine the speakers as pulling the audio through the system to emit sounds at a precise fixed rate. Everything else was controlled by that need — the video had to keep up (which typically mean the occasional dropped or “blocky” (not fully decoded) visual frame), the network had to deliver the needed packets well in time, and so on, including using the (predictable) audio output to calculate which video frame should be showing.

blf,

When you say hearing hearing is more sensitive than vision, I was wondering what exactly ‘sensitivity’ meant.

I have always been struck by how we can listen to (say) an orchestra and although our ears receive a single consolidated sound wave, our brains can distinguish between different instruments. On the other hand when we see an object, our eyes cannot break the light colors into its spectral components.

Contrasted with that, though the eye is very sensitive to a wide range of intensities. It can detect as few as a single or a few photons and up to quite intense light, whereas the range of sound that we can hear is narrower.

Interesting!

Mano@7, Perhaps I should have the human brain’s processing is more sensitive to disruptions. Individual instruments in an orchestra can be heard, as can individual dropped or misplayed notes. But the visual equivalent is lacking: Individual photons do not, to a human, constitute an important part of an entire scene or object in a scene; it is the large collection which does so (on the whole, ignoring special cases like negative astronomy images). (For “scene”, it probably makes sense to read “frame” here, or c.1/50th of second (ignoring interlaced fields for simplicity).) In contrast, a few out-of-place notes from a single instrument, even in a large orchestra, can be quite jarring.

Most visual scenes are quite “busy” (certainly contain more data), and so presumably contain much more “information”, than the corresponding audio. It takes longer for the brain to sort all the visual out and interpret the scene, and (from memory), the brain makes guesses and interpolations. (Speculating, that may be related to pareidolia?) Upshot is the brain rarely notices the occasional dropped video frame, albeit a dropped audio buffer-full is much more noticeable.

Apologies for being non-precise here and omitting references. My work in this general area was in the last century, and then wasn’t on the AVoD itself, but the supporting infrastructure. The challenge was to handle the rather large amount of data associated with video with the very persnickety (tight tolerances) of “scheduling” the audio output (that is, ensuring the speakers were fed essentially all the samples / waveforms at a constant rate). As previously said, the actual AVoD experts encouraged conceptualising the system as the speakers being in control; i.e., everything was keyed off maintaining constant-rate perfect audio output (and hence fiddling with the video to avoid going (badly-)out-of-sync).