One of Donald Trump’s most potent messages in the last election was his vision, given in almost apocalyptic language, about how important the election was for the soul of America, as expressed on Pat Robertson’s Christian Broadcasting Network.

Trump put the choice starkly for the channel’s conservative Christian viewers: “If we don’t win this election, you’ll never see another Republican and you’ll have a whole different church structure.” Asked to elaborate, Trump continued, “I think this will be the last election that the Republicans have a chance of winning because you’re going to have people flowing across the border, you’re going to have illegal immigrants coming in and they’re going to be legalized and they’re going to be able to vote, and once that all happens you can forget it.”

That this message resonated can be seen by post-election polls that shows that “Nearly two-thirds (66 percent) of Trump voters, compared to only 22 percent of Clinton voters, agreed that “the 2016 election represented the last chance to stop America’s decline.””

But the author of that article, Robert P. Jones, head of the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI), says that Trump’s victory signifies not the saving of America from the invading brown hordes but something else entirely.

The evidence, however, suggests that Trump’s unlikely victory is better understood as the death rattle of White Christian America-the cultural and political edifice built primarily by white Protestant Christians-rather than as its resuscitation.

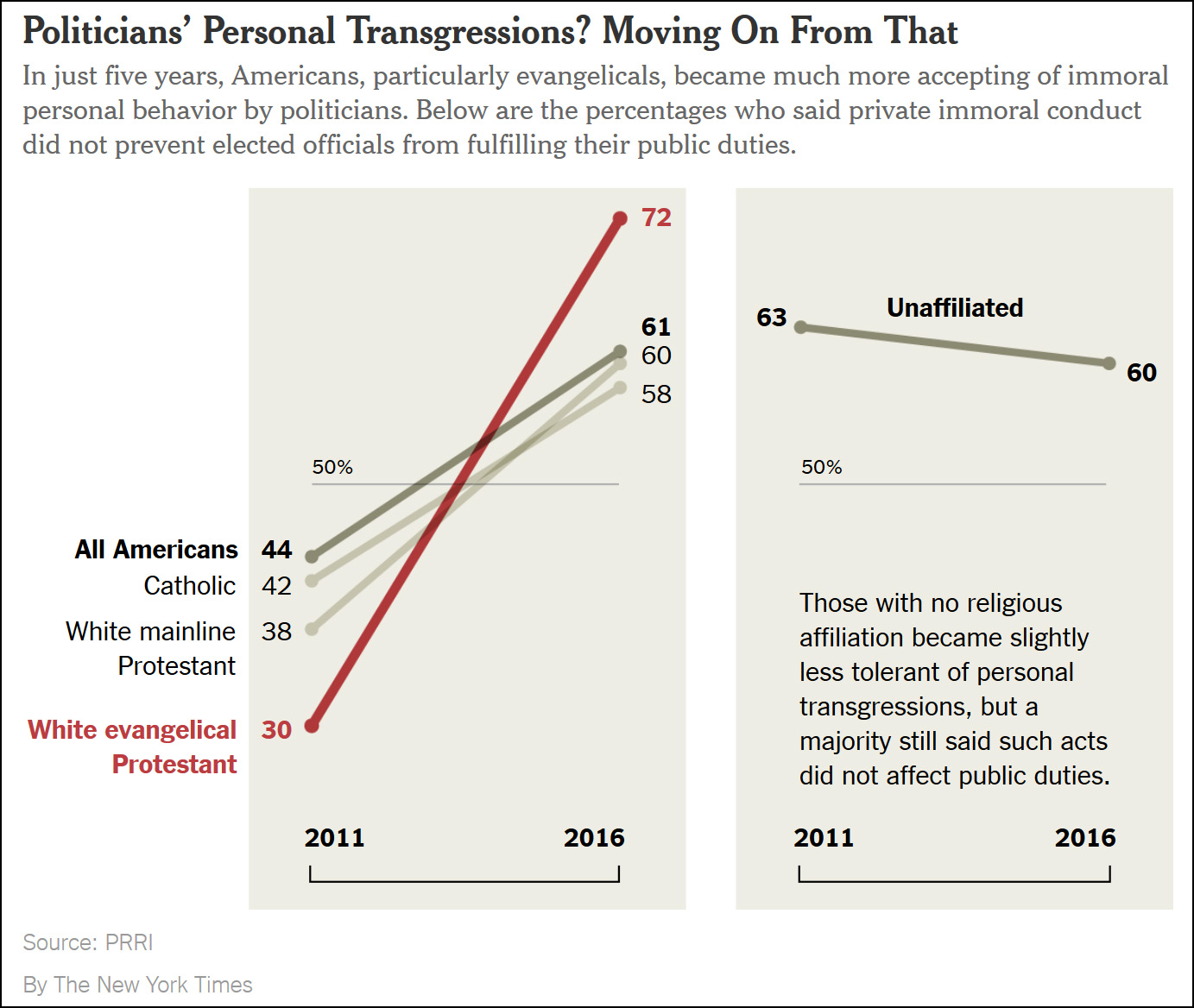

He says that in a dramatically short time, white evangelical Christians have done an almost complete about face on the issue of morality. One piece of evidence he points to is the dramatic switch officials in just five years from 2011 to 2016 in the attitudes of evangelical Christians towards the morality of elected. Other Christian groups also changed their views by large amounts but evangelicals were way ahead of the rest.. It is noteworthy that the views of the religiously unaffiliated remained largely stable.

This can be interpreted as due to the fact that in terms of personal morality Trump’s represented everything that evangelical Christians said they abhorred and yet they voted for him. Since it is impossible for even that group to pretend that Trump is a man of sterling morality, the only way for them to reconcile this was to say that personal qualities did not really matter. The wheels were greased for this transition by evangelical leaders like Jerry Falwell, Jr. and Robert Jeffress who lavishly praised Trump, the latter saying that a president’s faith is “not the only consideration, and sometimes it’s not the most important consideration” and that “I want the meanest, toughest, son-of-a-you-know-what I can find in that role, and I think that’s where many evangelicals are.”

Jones thinks that the trade-off that white Christian evangelicals have made, to swallow their formerly professed concern that the person they vote for president must be a person who holds high moral standards and support the very opposite in the hope that he will turn back the clock, is going to haunt them in the future.

White evangelicals have entered a grand bargain with the self-described master dealmaker, with high hopes that this alliance will turn back the clock. And Donald Trump’s installation as the 45th president of the United States may in fact temporarily prop up, by pure exertions of political and legal power, what white Christian Americans perceive they have lost. But these short-term victories will come at an exorbitant price. Like Esau, who exchanged his inheritance for a pot of stew, white evangelicals have traded their distinctive values for fleeting political power. Twenty years from now, there is little chance that 2016 will be celebrated as the revival of White Christian America, no matter how many Christian right leaders are installed in positions of power over the next four years. Rather, this election will mostly likely be remembered as the one in which white evangelicals traded away their integrity and influence in a gambit to resurrect their past.

Meanwhile, the major trends transforming the country continue. If anything, evangelicals’ deal with Trump may accelerate the very changes it was designed to arrest, as a growing number of non-white and non-Christian Americans are repulsed by the increasingly nativist, tribal tenor of both conservative white Christianity and conservative white politics. At the end of the day, white evangelicals’ grand bargain with Trump will be unable to hold back the sheer weight of cultural change, and their descendants will be left with the only real move possible: acceptance.

I was reminded of a famous passage in the Bible where Jesus says “For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?” (Mark 8:36). Jones is saying that evangelical Christians are not only going to lose their own soul, they will lose the world as well. Faustian bargains tend to have that quality.

One can only hope. Unfortunately, they’ve done a great deal of damage already, and their great white hope is still in office, so they are going to try for much more damage. It’s going to take a long time to recover as it stands now.

White evangelical Protestants worship money, that’s the reason they adore Trump. They also think that he’s crazy enough to start WW3, and thus bring Jesus to Earth, floating on a cloud.

Maybe but first we have to survive Trump’s time in power.

So this is literally measuring the bar being lowered?