Some of you may recall the case of Barronelle Stutzman, the owner of Arlene’s Flowers in Richland, Washington, who refused to accept a gay couple’s order to make floral arrangements at their wedding because of her religious objections to same-sex marriages. She said that she felt that if she were to accept the order, that would be tantamount to her endorsing such marriages.

The couple, joined by the state of Washington, sued her under the Washington Law Against Discrimination (WLAD) and the Consumer Protection Act (CPA). Stutzman lost at the various levels and the final unanimous decision by the entire nine-judge bench of the state Supreme Court was handed down last month that said that making floral arrangements did not constitute protected free speech and thus making floral arrangements could not be considered an endorsement of same-sex marriage. She has vowed to appeal to the US Supreme Court. A similar Colorado case involving the refusal to bake a cake for a same-sex wedding is pending before the US Supreme Court.

You can read the opinion here. One passage struck me in the opinion that I think gets to the heart of the issue.

Nevertheless, Stutzman argues that strict scrutiny is not satisfied in this case. She reasons that since other florists were willing to serve Ingersoll, no real harm will come from her refusal. And she maintains that the government therefore can’t have any compelling interest in applying the WLAD to her shop. In other words, Stutzman contends that there is no reason to enforce the WLAD when, as she puts it, “[N]o access problem exists.”

We emphatically reject this argument. We agree with Ingersoll and Freed that “[t]his case is no more about access to flowers than civil rights cases in the 1960s were about access to sandwiches.” As every other court to address the question has concluded, public accommodations laws do not simply guarantee access to goods or services. Instead, they serve a broader societal purpose: eradicating barriers to the equal treatment of all citizens in the commercial marketplace. Were we to carve out a patchwork of exceptions for ostensibly justified discrimination, that purpose would be fatally undermined. [Citations omitted-MS]

There are some who might wonder why we cannot find some accommodation for religious people like Stutzman who do not approve of same-sex marriages. That master of banal centrist pontifications, columnist David Brooks of the New York Times, one of those people who always thinks that his own views represents those of the majority of people, thinks that the reason why no accommodation is arrived at is because of rigid religious and secular purists, unlike sensible people like him who are not ideologues.

Most Americans are not hellbent on destroying religious institutions. If anything they are spiritually hungry and open to religious conversation. It should be possible to find a workable accommodation between L.G.B.T. rights and religious liberty, especially since Orthodox Jews and Christians aren’t trying to impose their views on others, merely preserve a space for their witness to a transcendent reality.

So basically, we secularists should allow a ‘space’ for the sincere beliefs of religious people. As usual, Brooks does not specify how that space is defined and his vagueness allows him to suggest that the florists and bakers should be allowed to discriminate against the LGBT community and thus elide the fundamental problem with that accommodationist strategy, which is that it is the courts that have to create that space and finding a legal rationale for doing so is not easy. Mark Silk explains the legal problem that such attempts encounter.

Courts in America aren’t allowed to determine the legitimacy of a particular religious belief — i.e. whether a Christian is entitled to believe that interracial marriage is contrary to God’s will. All they can decide is whether the belief is sincerely held.

…So here’s the issue.

If you think small business owners should be allowed to discriminate against any customer on the basis of any sincerely held religious belief, then fine. Be it same-sex marriage or interracial marriage or interfaith marriage or whatever marriage, the objecting service provider gets to have her way.

But if you want to forbid florists from refusing service to mixed-race couples but allow Baronelle Stutzman et al. to refuse service to a same-sex couples, you have to come up with some persuasive secular reason for considering discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation less deserving of legal protection than discrimination on the basis of race.

I can’t.

Silk is not quite right that there can be no legal reasons to distinguish between different kinds of discrimination. The courts can and have distinguished between different kinds of discrimination but they cannot arbitrarily pick and choose which ones to allow and which ones to forbid. Courts have to decide whether laws are subject to the lowest standard of ‘rational basis’, the next level of ‘heightened scrutiny’, or the highest level of ‘strict scrutiny’, and then apply those standards uniformly. (See here for what each term implies.) As the Washington Supreme Court said in its opinion:

Neutral, generally applicable laws burdening religion are subject to rational basis review, while laws that discriminate against some or all religions (or regulate conduct because it is undertaken for religious reasons) are subject to strict scrutiny.

Stutzman argues that the WLAD is subject to strict scrutiny under a First Amendment free exercise analysis because it is neither neutral nor generally applicable. She is incorrect.

A law is not neutral, for purposes of a First Amendment free exercise challenge if “the object of [the] law is to infringe upon or restrict practices because of their religious motivation.” Stutzman does not argue that our legislature passed the WLAD in order to target religious people or people whose religions dictate opposition to gay marriage. Instead, she argues that the WLAD is unfair because it grants exemptions for “religious organizations”-permitting these organizations to refuse marriage services-but does not extend those same exemptions to her.

We disagree. The cases on which Stutzman relies all address laws that single out for onerous regulation either religious conduct in general or conduct linked to a particular religion, while exempting secular conduct or conduct associated with other, nontargeted religions.

As the Washington Supreme Court said, these case are not about access to flower arrangements or cakes or photographs, any more than the sit-ins during the civil rights struggles were about access to food. Anti-discrimination laws “serve a broader societal purpose: eradicating barriers to the equal treatment of all citizens in the commercial marketplace. Were we to carve out a patchwork of exceptions for ostensibly justified discrimination, that purpose would be fatally undermined.”

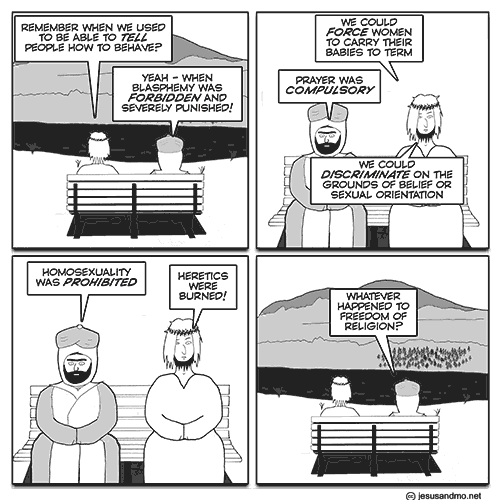

Let Jesus & Mo have the last word.

The individuals who want to discriminate DO HAVE such spaces -- they are called churches.

The problem (in Europe, too) is to limit the damage they do.

1. hospitals (how to get abortionforbidders out of being considered a fullservice hospital? They are not.)

2. kindergardens and schools

3. tax exemptions (plus German “church tax”)

4. lobbying

to name but the worst areas where prejudices and hateful worlviews spill over to anyone around..

In a computer game we could program a business as “Christian florals” or, to use a gamey word “Euthanasia forbidder bakery” when it is surrounded by others serving anyone, but I doubt very much that this would work in reality. I do have problems with FINDING MDs and hospitals in the area I live, which do not force religion upon me!!!

AND I am practised to this search , being a lifetime atheist with many moves!

It is plain and repetitive dominionism, the cartoon summons it up nicely.

This is the 21st century. Why are we still arguing about made-up rules proposed by imaginary gods?

ragove314

Dunno.

Why are we still numbering our calendar years based on a never-existed demi-god?

@chigau

Too much work to change. And it’s a simple and stable system with permanency, unlike the old Roman system which was based on lunar cycles and politics with local variations.

I’d change the months before I’d change the years. There are plenty of good calendar reform proposals out there, and very few advocates messing with the year numbers. We have to set an arbitrary year zero anyway. Is there a very much better reference than Jesus? Historical existence or not, he’s definitely well-known.

I’m satisfied with the religious outcry over using BCE/CE instead of BC/AD. Delicious tears of religious frustration!

Oh no, it’s like the year 2000 again when people said that was the start of the millenium. We start counting from 1. Count to 10 aloud and see what the first number you say is. We didn’t set an abritrary year zero. An arbitrary year 1 was set. When people talk about the birth of the demi-god, who according to most christians was the god (trinity), they don’t say he was born in year zero and don’t date it from year zero. It’s the first year anno domini.

Sorry it’s 1 anno domini. Which is different.