Douglas Hofstadter, author of the fascinating book, Gödel, Escher, Bach, is someone I’ve admired for a long time, both as an expositor and an original thinker.

But he goes badly wrong in a few places in this essay in the Atlantic Monthly. Actually, he’s said very similar things about AI in the past, so I am not really that surprised by his views here.

Hofstadter’s topic is the shallowness of Google Translate. Much of his criticism is on the mark: although Google Translate is extremely useful (and I use it all the time), it is true that it does not usually match the skills of the best human translators, or even good human translators. And he makes a strong case that translation is a difficult skill because it is not just about language, but about many facets of human experience.

(Let me add two personal anecdotes. I once saw the French version of Woody Allen’s movie Annie Hall. In the original scene, Alvy Singer (Woody Allen) is complaining that a man was being anti-semitic because he said “Did you eat?” which Alvy mishears as “Jew eat?”. This was translated as “Tu viens pour le rabe?” which Woody Allen conflates with “rabbin”, the French word for “rabbi”. The translator had to work at that one! And then there’s the French versions of the Harry Potter books, where the “Sorting Hat” became the “Choixpeau”, a truly brilliant invention on the part of the translator.]

But other things Hofstadter says are just … wrong. Or wrong-headed. For example, he says, “The bailingual engine isn’t reading anything–not in the normal human sense of the verb ‘to read.’ It’s processing text.” This is exactly the kind of complaint people made about the idea of flying machines: “A flying machine isn’t flapping its wings, so it cannot be said to fly in the normal human understanding of how birds fly.” [not an actual quote] Of course a computer doesn’t read the way a human does. It doesn’t have an iris or a cornea, it doesn’t use its finger to turn the page or make the analogous motion on a screen, and it doesn’t move its lips or write “How true!” in the margins. But what does that matter? No matter what, computer translation is going to be done differently from the exact way humans do it. The telling question is, Is the translation any good? Not, Did it translate using exactly the same methods and knowledge a human would? To be fair, that’s most of his discussion.

As for “It’s processing text”, I hardly see how that is a criticism. When people read and write and speak, they are also “processing text”. True, they process text in different ways than computers do. People do so, in part, taking advantage of their particular knowledge base. But so does a computer! The real complaint seems to be that Google Translate doesn’t currently have access to, or use extensively, the vast and rich vault of common-sense and experiential knowledge that human translators do.

Hofstadter says, “Whenever I translate, I first read the original text carefully and internalize the ideas as clearly as I can, letting them slosh back and forth in my mind. It’s not that the words of the original are sloshing back and forth; it’s the ideas that are triggering all sorts of related ideas, creating a rich halo of related scenarios in my mind. Needless to say, most of this halo is unconscious. Only when the halo has been evoked sufficiently in my mind do I start to try to express it–to ‘press it out’–in the second language. I try to say in Language B what strikes me as a natural B-ish way to talk about the kinds of situations that constitute the halo of meaning in question.

“I am not, in short, moving straight from words and phrases in Language A to words and phrases in Language B. Instead, I am unconsciously conjuring up images, scenes, and ideas, dredging up experiences I myself have had (or have read about, or seen in movies, or heard from friends), and only when this nonverbal, imagistic, experiential, mental ‘halo’ has been realized—only when the elusive bubble of meaning is floating in my brain–do I start the process of formulating words and phrases in the target language, and then revising, revising, and revising.”

That’s a nice description — albeit maddeningly vague — of how Hofstadter thinks he does it. But where’s the proof that this is the only way to do wonderful translations? It’s a little like the world’s best Go player talking about the specific kinds of mental work he uses to prepare before a match and during it … shortly before he gets whipped by AlphaGo, an AI technology that uses completely different methods than the human.

Hofstadter goes on to say, “the technology I’ve been discussing makes no attempt to reproduce human intelligence. Quite the contrary: It attempts to make an end run around human intelligence, and the output passages exhibited above clearly reveal its giant lacunas.” I strongly disagree with the “end run” implication. Again, it’s like viewing flying as something that can only be achieved by flapping wings, and propellers and jet engines are just “end runs” around the true goal. This is a conceptual error. When Hofstadter says “There’s no fundamental reason that machines might not someday succeed smashingly in translating jokes, puns, screenplays, novels, poems, and, of course, essays like this one. But all that will come about only when machines are as filled with ideas, emotions, and experiences as human beings are”, that is just an assertion. I can translate passages about war even though I’ve never been in a war. I can translate a novel written by a woman even though I’m not a woman. So I don’t need to have experienced everything I translate. If mediocre translations can be done now without the requirements Hofstadter imposes, there is just no good reason to expect that excellent translations can’t be eventually be achieved without them, at least in the same degree that Hofstadter claims.

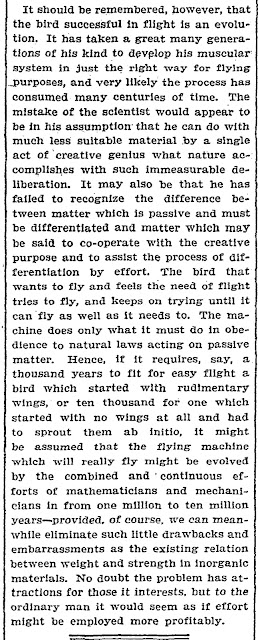

I can’t resist mentioning this truly delightful argument against powered mechanical flight, as published in the New York Times:

The best part of this “analysis” is the date when it was published: October 9, 1903, exactly 69 days before the first successful powered flight of the Wright Brothers.

Hofstadter writes, “From my point of view, there is no fundamental reason that machines could not, in principle, someday think, be creative, funny, nostalgic, excited, frightened, ecstatic, resigned, hopeful…”.

But they already do think, in any reasonable sense of the word. They are already creative in a similar sense. As for words like “frightened, ecstatic, resigned, hopeful”, the main problem is that we cannot currently articulate in a suitably precise sense what we exactly mean by them. We do not yet understand our own biology enough to explain these concepts in the more fundamental terms of physics, chemistry, and neuroanatomy. When we do, we might be able to mimic them … if we find it useful to do so.

Addendum: The single most clueless comment to Hofstadter’s piece is this, from “Steve”: “Simple common sense shows that [a computer] can have zero “real understanding” in principle. Computers are in the same ontological category as harmonicas. They are *things*. As in, not alive. Not conscious.

Furthermore the whole “brain is a machine” thing is a *belief* based on pure faith. Nobody on earth has the slightest idea how consciousness actually arises in a pile of meat. Reductive materialism is fashionable today, but it is no less faith-based than Mormonism.”

Hofstadter seems to be the type who is both enthusiastic about AI but who deeply wants to believe some areas are ‘special’ and humans will remain champions, with machines only producing clearly inferior work.

His objections here seem a bit like Chomsky’s. It’s a complaint that machines don’t reduce statements to some kind of ‘basic idea’ or some ‘universal grammar’ and then put that into the new language. It’s also that older people in AI remember the days when machines would be programmed to understand using some kind of logical relations instead of by having massive amounts of data thrown at them.

I think you are missing the point entirely. What Hofstadter is saying is “the state of the art in machine translation is rubbish”, which isn’t wrong. You say, machines “*do* think, in any reasonable sense of the word”, which is complete bollocks. What machines do, and this is pretty much universal among machine-learning algorithms, is construct a hyperplane arrangement [in a vector space that represents the particular data in question], each of whose cells are labelled by the label that fits the training data best (e.g. “cats”, “dogs”, “trousers”, for an image recognition algorithm). The machines *don’t* think, they just give an output that is consistent with the input they are given. To be sure, given sufficient [language A]-[language B] pairs of paragraphs, they will be able to match humans at some point, but currently they really aren’t up to the task, beyond simple “what does this particular word (or maybe short phrase) mean”.

With your “this is what they said about flight” analogy, it kind of seems like you are going for a “technology pessimists are luddites, and look how wrong these other luddites were” argument; this flounders on the fact that Hofstadter is *right*: modern AI algorithms are *not* concerned with intelligent problem-solving, but merely data-conditioned pattern-matching. The successes of e.g. AlphaZero are due to the fact that simple games like Chess and Go are particularly amenable to that kind of “thinking”.

It is worth noting that Douglas Hofstadter’s research group is one of the last remnants of the early AI research aiming at creating artificial minds; most of the field switched focus in the early 80’s aiming for the lower-hanging fruits of “machine learning”, meaning automating low-level tasks.

“You say, machines “*do* think, in any reasonable sense of the word”, which is complete bollocks.”

What is your definition of “think”? You must have one, or otherwise you would not be able to say that my claim is “complete bollocks”. Please let me know.

it kind of seems like you are going for a “technology pessimists are luddites, and look how wrong these other luddites were” argument

Not exactly. The NYT quote is delightful because it made the same mistake Hofstadter makes: it assumed that the only way to achieve powered flight was to do something similar to the way birds achieved it, through some sort of evolutionary process. And as a bonus it contains a criticism that was common in the early days of computers: computers can’t think and people can’t fly because “The machine only does what it must do in obedience to natural laws acting on passive matter.”

It looks to me like you didn’t read and reflect carefully enough on the quoted passage.

I got fascinated with AI (i.e. read a few books and tried to write an Eliza-a-like for my home computer) in the early 80s. I quickly got disillusioned with it because it rapidly became clear that the truest thing said about AI is this: AI is whatever we can’t do yet. Beating a human at chess would require a computer to be an AI… oh it’s been done? By brute force and speed? Obviously not actual AI. Go, though, that’s beyond any mere machine. That’ll take an AI… which is not what AlphaGo is, obvs. Besides, they couldn’t process natural language in real time and respond to, e.g. questions on a quiz show, that would take…. oh, Watson’s not an AI, not as such, it’s just a something something database something.

I confidently predict that after an entirely artificial actor has won an Oscar for a performance in a film for which the screenplay was written entirely without human intervention, there’ll still be reactionary organics saying true AI will “probably not be achievable until about fifty years from now”.

But could you do so if you had never heard about, read about, seen pictures or video of… a war? And not just factual descriptions of tactics or strategy, but the Iliad, or Wilfred Owen’s war poetry?

Well, that’s “just an assertion”, and in fact more so than Hofstadter’s claim.

The comparison with go is an interesting one. I was very impressed (as a low-grade player – about 10 kyu – and a former AI researcher) by AlphaGo, but a game of go is still a situation in which there are only a finite (and relatively small) number of options at any given point. Currently, research into the potential of “deep learning” is at a fairly early stage, and I would expect considerable advances over the next few years – and then, a slowdown as its limitations become evident. And in due course, another new approach which overcomes some of those limitations.

Since he explicitly says the opposite in this quote:

I wonder what leads you to that conclusion.

But could you do so if you had never heard about, read about, seen pictures or video of… a war?

One of the most celebrated of all war novels was written by Stephen Crane, who had never been in a war, nor seen video of a war. And blind people have written excellent novels about things they’ve never seen, containing detailed visual descriptions of objects and people.

I wonder what leads you to that conclusion

I can’t speak for smrnda, but Hofstadter says it more or less explicitly in his text: he is a “a lifelong admirer of the human mind’s subtlety”; and “Such a development would cause a soul-shattering upheaval in my mental life. Although I fully understand the fascination of trying to get machines to translate well, I am not in the least eager to see human translators replaced by inanimate machines. Indeed, the idea frightens and revolts me. To my mind, translation is an incredibly subtle art that draws constantly on one’s many years of experience in life, and on one’s creative imagination. If, some “fine” day, human translators were to become relics of the past, my respect for the human mind would be profoundly shaken, and the shock would leave me reeling with terrible confusion and immense, permanent sadness.”

My definition of “thinking”: isn’t really relevant, what I took objection to was the “in any reasonable sense of the word” part. Clearly there are reasonable people (e.g. Hofstadter, or myself) who don’t consider what neural nets (or other “AI” algorithms) do to be thinking, so whatever “thinking” means, there is a reasonable sense of the word that doesn’t include whatever machines do.

Techno-ludditry: I waved off the old clipping as a parallel to Hofstadter’s argument precisely because I don’t agree with you that he’s making a mistake.

Fundamentally, our minds work by the principle of

[extremely basic thing happens in many small units] -> [things get complicated] -> [mind]

and there’s nothing wrong with the basic idea of AI, which is to change the first part from being made of neurons to being made of transistors. Where I think we diverge, and here I agree with Hofstadter, is that the current state of the art is lacking a lot of the “things get complicated” part. It’s a little too simple, and fails in very stupid ways (e.g. the translation derps as in the article). What Hofstadter is saying is that until the technology advances to a much more complex point (so it can have internal representations of higher-level things than now, aka “feelings”, “ideas” or whatever) he’s not ready to call it intelligent. It’s hard to say what a “mind” is, but to me something as simple as the current AI technology certainly doesn’t qualify.

A little side-note on evolution: you seem dismissive of the idea that true intelligence can only be achieved via some kind of evolutionary process. I used to think like that, but have over time grown skeptical due to how little progress has been made by the opposite strategy of trying to be clever. It may be that we just aren’t clever enough to make something as complicated as a mind by hand, as it were, and will only get there by some kind of evolutionary process. After all, the reason why “true AI” has been twenty years away since the very beginning is a continuous loop of “I understand this now -> oh wait, this is more complicated that I thought”.

so whatever “thinking” means, there is a reasonable sense of the word that doesn’t include whatever machines do.

OK, fine. But what is that sense?

An alternative might be that neither you nor Hofstadter have seriously considered what you even mean by “thinking”, and if you did, you wouldn’t say what you did.

you seem dismissive of the idea that true intelligence can only be achieved via some kind of evolutionary process

I think this might be a very good route in practice, but I see no reason why it would be the only way. Of course, “evolutionary process” is so vague that one might reasonably say that the methods we are currently using, involving multiple people trying and failing on multiple approaches, is itself an “evolutionary process”.

I also want to point out that Hofstadter’s prediction about chess in GEB was wildly off the mark. It is a counterexample to your last paragraph, because after Deep Blue Hofstadter said just the opposite: more or less (not an exact quote) ‘now that chess programs beat people I see that chess was much less complicated than I thought’.

AI researchers just can’t win! Successes are dismissed and failures are elevated to general rules.

Here’s the link to the actual Hofstadter quote.

http://besser.tsoa.nyu.edu/impact/w96/News/News7/0219weber.html

If you absolutely want to force me to nail down a definition, I can give you “something similar to what I do when I think” as a dodge. Basically I don’t think it matters precisely what we mean by “thinking”, because at this point our machines clearly (to me) aren’t doing it. In other words, we have some way to go before it becomes neccessary to pin down definitions, and we can enjoy the luxury of ambiguity a while longer.

About chess: Hofstadter was actually right on the money by saying chess turned out to be less complicated than we thought. We used to think chess was the sort of thing you needed a human-level mind to play at a human level, but it turns out you can beat a human with a relatively simple algorithm (meaning anyone with some programming experience can be taught how it works in not that much time). Thus: chess turns out to be simpler than we thought it was. A step up in complexity: we used to think the same about Go (that is, “Go is in the need-a-real-brain-to-beat-humans”-class of complexity), but again, it turns out you can beat a human with a relatively simple algorithm (albeit a more complex one than for chess).

It isn’t “AI researchers can’t win”, it’s the more we know, the more we know how much we don’t know yet. The development of chess-playing algorithms is a great example, of discovering how complex the world is by finding out what sort of things are actually (relatively) easy. Compare playing chess (surpassed humans ’97 was it?) to translation (currently almost-but-not-quite-there), we have now discovered by trying to solve these problems how hard they are, and separated them (in complexity) from harder tasks we still don’t know how to solve by algorithm (say, writing good music). They used to think it was doable to make a “true” AI, they now don’t think that’s happening any time soon, because we’ve realised the problems we were doing well with (e.g. chess) are actually much easier than the full monty of Mind.

There’s actually quite a lot Hofstadter got wrong in GEB, but that’s maybe a question for another time. Perhaps it’s time to re-reread it again soon to check how much I still agree with?

Basically I don’t think it matters precisely what we mean by “thinking”, because at this point our machines clearly (to me) aren’t doing it.

OK, but machines clearly (to me) are doing it. I am willing to go through the definitions of “to think” in an online dictionary and say precisely why I think machines fulfill those definitions. Are you interested in a blog post where you do the same, but say they don’t? We could alternate.

Turing cut through all this. If it’s not indistinguishable from a human in conversation, it’s not thinking. If it is, it is. There’s your definition, and we are nowhere close.

Well, Turing didn’t quite say that (read his original paper!) and it’s clear that your criterion is much too narrow. For example, a thinking alien being from another galaxy who knows a lot about its own culture/language/history would probably be distinguishable from a human. Similarly for a human who doesn’t share any of your cultural referents.

For another, there actually have been programs that have fooled people into thinking they were human. Read about the Loebner prize and https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/jun/08/super-computer-simulates-13-year-old-boy-passes-turing-test .