Science is always working a tough room. It’s inherently progressive — we’re constantly achieving incremental improvements in our understanding, with occasional lurches forward…and sometimes sudden lurches backward, when we realize that we got something wrong. We’re performing for a crowd, the general citizenry and most importantly, the funding agencies, that expect us to fix problems and make the world better, and they’re a fickle bunch who will turn on us with disdain if we don’t keep delivering new medical therapies and tinier electronics and more spectacular robots landing on alien worlds.

Unfortunately, there are a couple of sources of tension in our act.

One problem is that we aren’t doing what everyone thinks we’re doing. The world outside the sciences thinks we’re all about making material improvements in your standard of living, or increasing our competitiveness with other countries. Wrong. We do what we do to increase our understanding. There is an applied side to science that is asking about, for instance, better treatments for cancer, but it’s built on a foundation of scientists just asking, “how do cells work?”

An analogy: imagine building race cars. Everyone watching is thinking that it’s all about winning races (that’s also the case for the backers who are paying for all the machines). But the scientists are the ones who are just thinking about what’s going on inside the engine, tracing the flow of fuel and energy, optimizing and adjusting to make it work. Put a scientist in the driver’s seat, and she wouldn’t be thinking about winning the race; if she heard a mysterious “ping!” at some point, her instinct would be to just pull over then and there and take things apart until she’d figured out what caused it. And figuring out the ping would be more satisfying than finishing the race.

So everyone criticizes the scientist for not winning any races, but the scientist is feeling triumphant because her performance wasn’t what you thought it was — she learned a little bit more about what makes the engine tick, and you should be happy about that!

So that’s one source of tension. Here’s another: funding and public support thrives on positive results, that constant reassurance that yes, we’re proceeding apace towards the finish line, but science itself thrives on criticism. Probing and patching and making fruitful errors and getting criticism that forces us to reconsider our premises and rebuild our hypotheses…that’s the progressive force behind science. And we should be appreciative when someone tells us that a major chunk of research is invalid (and as scientists, we are), but at the same time, we’re thinking that if we have to retool our labs, retrain our students, rethink everything from the ground up, as exciting as it is in a scientific sense, it’s going to be a really hard sell to NSF or NIH. The granting agencies, and the media, love the safe, reliable churn of data that looks like progress from the outside.

Which brings me to an interesting argument. On one side, John Horgan gets all cynical and critical of science, pointing out deep and fundamental flaws in peer review, the overloading of science journals with poor quality work, the lack of progress in many of our goals for science, and bemoaning the reassuring positivity of the media towards science.

…I’m struck once again by all the “breakthroughs” and “revolutions” that have failed to live up to their hype: string theory and other supposed “theories of everything,” self-organized criticality and other theories of complexity, anti-angiogenesis drugs and other potential “cures” for cancer, drugs that can make depressed patients “better than well,” “genes for” alcoholism, homosexuality, high IQ and schizophrenia.

And he’s right! We don’t have any cures for cancer or schizophrenia, and as he also points out, the scientific literature is littered with trash papers that can’t be replicated.

But on the other side, Gary Marcus says wait a minute, we really have learned a lot.

Yet some depressed patients really do respond to S.S.R.I.s. And some forms of cancer, especially when discovered early, can be cured, or even prevented altogether with vaccination. Over the course of Horgan’s career, H.I.V. has gone from being universally fatal to routinely treatable (in nations that can afford adequate drugs), while molecular biologists working in the nineteen eighties, when Horgan began writing, would be astounded both by the tools that have recently been developed, like whole-genome-sequencing, and the detail with which many molecular mechanisms are now understood: reading a biology textbook from 1983 is like reading a modern history text written before the Second World War. Then there is the tentative confirmation of the Higgs boson; the sequencing of Neanderthal DNA; the discovery of FOXP2, which is the first gene decisively tied to human language; the invention of optogenetics; and definitive proof that exoplanets exist. All of these are certifiable breakthroughs.

And he’s right!

See what I mean? It’s conflict and tension all the way through. The thing is that the two are looking at it from different perspectives. Horgan is asking, “how many races have we won?” and finds the results dispiriting. Marcus is asking “have we figured out how the engine works?” and is pleased to see that there is an amazing amount of solid information available.

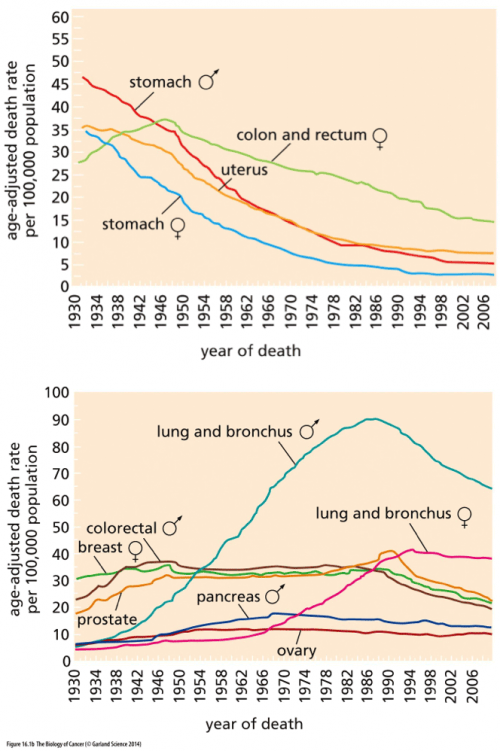

Here, for example, are some data on cancer mortality over time. In this instance, we are actually looking at the science as a race: the faster that we can get all those lines down to zero, the happier we’ll all be.

Look at the top graph first. That’s where we’re doing well: the data from stomach and colon and uterine cancer show that those diseases are killing a smaller percentage of people every year (although you can probably see that the curves are beginning to flatten out now). Science did that! Of course, it’s not just the kind of science that finds a drug that kills cancer; much of the decline in mortality precedes the era of chemotherapy and molecular biology, and can be credited to better sanitation and food handling (hooray for the FDA!), better diagnostic tools, and changes in diet and behavior. We’re winning the war on cancer!

Wait, hold on a sec, look at the bottom graph. It’s more complicated than that. Look at lung cancer; science was helpless against the malignant PR campaigns of the tobacco companies. Some cancers seem relentless and unchangeable, like pancreatic and ovarian cancer, and show only the faintest hint of improvement. Others, like breast cancer, held steady in their rate for a long time and are just now, in the last few decades, showing signs of improvement. It’s complicated, isn’t it? Horgan is right to point to the War on Cancer and say that the complex reality is masked by a lot of rah-rah hype.

But at the same time…Horgan got his journalism degree in 1983, and I got my Ph.D. in 1985. He’s on the outside looking in and seeing one thing; over that same time period, I’ve been on the inside (still mostly looking in), and I’ve seen something completely different.

If I could show my 1985 self what 2013 science publishes as routine, 1985 self would be gibbering in disbelief. Transgenic mice? Shuffling genes from one species to another? Whole genome sequencing? Online databases where, with a few strokes of the keyboard, I can do comparisons of genes in a hundred species? QTLs that allow us to map the distribution of specific alleles in whole populations? My career spans an era when it took a major effort by a whole lab group to sequence a single gene, to a period when a grad student could get a Ph.D. for completing the sequencing of a single gene, to now, when we put the DNA in a machine and push a button.

You can look at those charts above and wonder where the cure for cancer is, or you can look at all the detailed maps of signaling pathways that allows scientists to say we understand pretty well how cancer works. Do you realize that hedgehog was only discovered in 1980, and the activated human ras oncogene was only identified in 1982? It’s rather mindblowing to recognize that genes that we now know are central to the mechanisms of cancer have only emerged in the same short period that Horgan finds disappointing in the progression of science.

Everyone on the outside is missing the real performance!

Unfortunately, a growing problem is that some of the people on the inside are also increasingly focused on the end result, rather than the process, and are skewing science in unfortunate directions. There’s grant money and tenured positions on the line for getting that clear positive result published in Cell! As Horgan points out, “media hype can usually be traced back to the researchers themselves”. We’ve seen that with dismaying frequency; recently I wrote about how the ENCODE project seems to have fostered a generation of technicians posing as scientists who don’t understand the background of biology (and Larry Moran finds another case published in Science this week!). We’re at a period in the culture of science when we desperately need more criticism and less optimism, because that’s how good science thrives.

That’s going to be tricky to deliver, though, because the kind of criticism we need isn’t about whether we’re winning the race or not, or translating knowledge into material benefits or not, but whether the process of science is being led astray, and how that’s happening: by the distorting influence of big biomedical money, by deficiencies in training scientists in big picture science, or by burdensome biases of science publication, or by all of the above and many more.

But ultimately we need the right metrics and to have well-defined outcomes that we’re measuring. It doesn’t help if the NIH measure success by whether we’ve cured cancer or not, while scientists are happily laboring to understand how cell states are maintained and regulated in multicellular eukaryotic organisms. Those are different questions.