Vaccinate your kids.

Tara Smith is an expert in infectious diseases, and she also has a new baby (congratulations!) fussing up her house, so she knows what she’s talking about…and she explains why she vaccinated her kids. Just do it. It’s the only smart choice.

I was looking over the Discovery Institute’s Evolution News and Views site, prior to forgetting about it. I mentioned that I am forced to revamp my email handling and was going to be blocking a lot of noise from my work address, and as I was reviewing what domains I needed to allow through, I noticed that boy-howdy, I get a lot of crappy spam from the Discovery Institute (all of which is now getting blocked). So I actually bothered to go through one of their links and see what they’re babbling about now.

General impression: the Discovery Institute is really obsessed with Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey. They’re flailing about angrily about how it’s just bad and awful and a serious threat. Good work, Neil deGrasse Tyson, you’re obviously doing something right!

The other thing that has them worked up, though, surprised me a little bit: they’re kind of peeved that scientists keep pointing to this evidence that humans and chimpanzees are close relatives, and they throw around a lot of sciencey words trying to cast doubt on the idea that we’re related. They don’t come out and openly deny it, exactly — but it’s still the stupid old yokel’s denial that they didn’t come from no monkey, stated a little more ornately to make it sound less stupid. They failed; it still sounds stupid. But have no fear, they’ve put their Top Man and Chief Scienceologist, Casey Luskin, on the job.

Oh, wait. That makes it even stupider.

It should be pointed out first that ID does not have an “official” position on common descent. Guided common descent would be compatible with intelligent design. However, many ID theorists do question the evidence offered for universal shared ancestry.

Scratch an ID theorist

, and what do you find? Just another dumb evolution denier. Common descent, and in particular the close relationship between humans and other apes, is not in question at all, but the Discovery Institute can’t even muster an official position on it. Other basic science questions the Discovery Institute will not say a word about: the age of the earth, whether the human race was reduced to an 8 person bottleneck by a big flood 4,000 years ago, Jesus: magic man or genetic engineer?, and just how ignorant is Casey Luskin, anyway?

The way Luskin questions the shared ancestry of humans and chimpanzees is to simply dump, with virtually no explanation, lists of legitimate scientific papers that show various common genetic properties. Codon frequency can affect transcription rates, so synonymous changes in nucleotides of a sequence may have phenotypic effects; yes, this is true. Position effects can also affect phenotype; this is also true — translocations, movement of a chunk of DNA from one location to a different one, can modify gene expression. Pseudogenes aren’t always free from selectional constraints, and sometimes also modulate the expression of other genes — yeppers. These are also all basic facts that we’ve known for decades, that have been worked out by scientists, not creationists, and that have absolutely no relevance to the question of whether chimpanzees and humans are closely related. They say that there are many complicated ways in which variation can arise in a lineage, that it’s difficult to reduce the degree of difference between two species to a single number, but everyone who does any bioinformatics at all already knows that.

For instance, here are two sequences. How different are they from one another? Can you give me a simple number that summarizes the variation?

1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10-A-B-C-D-E-F-G-H-I-J

1-2-3-4-A-B-C-D-E-F-G-H-5-6-7-8-9-10-I-J

Biologists are already intimately familiar with the difficulty of describing the variation in sequence between species. If it were just a matter of a string of DNA accumulating point mutations, it would be relatively easy, and we could simply measure how many positions had acquired a novel nucleotide, but mutations can be all kinds of other things, like translocations or inversions or deletions or duplications. So Casey Luskin high-handedly informing us that measuring variation is more difficult than just enumerating a linear series of nucleotide changes is absolutely nothing new, and telling us that pairwise comparisons are complex, therefore we should doubt the relationship between two primates, is utterly bogus and logically fallacious.

The question should be, “if we compare the differences between chimpanzee and human genomes, messy and complicated as they are, are they less different from one another than, say, the human and gorilla genomes? Or the human and mouse genomes? Or the human and fly genomes?” Just comparing any two species can only tell you that they have differences and similarities; you need to do multiple comparisons between different species and an outgroup to get a feel for the relative magnitude of differences.

Luskin’s only approach, carried to an excruciating degree, is to simply say there sure are a lot of differences between humans and chimpanzees (six million years of divergence will do that), therefore it is reasonable to question their relatedness. Yeah, and my brother is a few inches taller than I am and has red hair, therefore we can’t possibly be related.

Casey Luskin isn’t the only IDiot on staff at IDiot Central. They also have Ann Gauger. She does exactly the same thing, citing a Science article that discusses the difficulties of quantifying the differences between genomes. It also points out that the subtle differences can be immensely significant, which Gauger makes much of.

Here are some large-scale differences that get overlooked in the drive to assert our similarity. Our physiology differs from that of chimps. We do not get the same diseases, our brain development is different, even our reproductive processes are different. Our musculoskeletal systems are different, permitting us to run, to throw, to hold our heads erect. We have many more muscles in our hands and tongues that permit refined tool making and speech.

Golly, yes. We’re different from chimpanzees. We do things they don’t, and they do things we don’t. My brother has red hair, and mine is brown. None of this is controversial, or in any way challenges the idea of relatedness or degree of relatedness. To do that, you have to compare multiple lineages and quantify all these variations — we go beyond simple nucleotide counts, for instance, to ask how many duplications? How many regulatory changes? How many deletions? And when we measure those, doing more than just asking how many bases are different between two different genes, we also get measures of relatedness. And they line up!

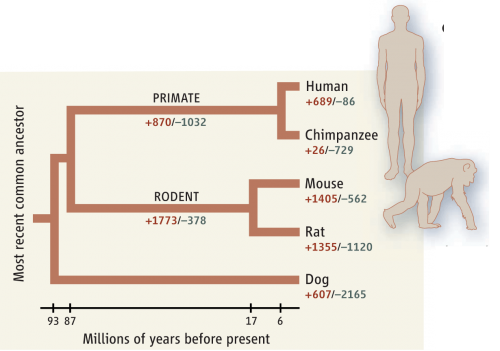

Gauger notably fails to refer to the figure in the article she cites.

Throughout evolution, the gain (+) in the number of copies of some genes and the loss (–) of others have contributed to human- chimp differences.

Why, Ann, why? Because it actually demolishes your whole argument by demonstrating degrees of similarity between different species using a different index, the number of gene duplications and deletions? If you want to question chimp/human propinquity, you don’t get to simply ignore the data we use to justify that.

But of course, Gauger wants to argue that the unique attributes of humans are somehow especially special and deserve special consideration — that they completely set us apart from other animals.

Going beyond the physical, we have language and culture. We are capable of sonnets and symphonies. We engage in scientific study and paint portraits. No chimp or dolphin or elephant does these things. Humans are a quantum leap beyond even the highest of animals. Some evolutionary biologists acknowledge this, though they differ in their explanations for how it happened.

You know, I would agree that we carry out certain things to a greater degree than other animals — we do have more elaborate language, more intricate technologies, much more complex art. But other animals exhibit curiosity, playfulness, exploration, communication, and we can look at a chimpanzee, for instance, and see attributes that we’ve amplified and expanded. The roots of our humanity are patent in other species, and we are not qualitatively unique. Furthermore, other species have abilities we don’t. Can you sing under water and have your music transmitted over hundreds of miles of ocean? Can you wash your car with your nose? Aren’t you a little bit embarrassed by the puniness of your teeth?

But Gauger is oblivious to the astounding beauty of other organisms — it’s all about us.

In truth, though, we are a unique, valuable, and surprising species with the power to influence our own futures by the choices we make. If we imagine ourselves to be nothing more than animals, then we will descend to the level of animalism. It is by exercising our intellects, and our capacity for generosity, foresight, and innovation, all faculties that animals lack, that we can face the challenges of modern life.

Generosity? Has Ann Gauger never had a dog?

As for innovation, yeah, I agree. Humans do have some novelties. Here’s a paper about the de novo origin of human protein-coding genes, that compared those chimpanzee and human genomes looking for just the unique genes in the human lineage (this is only one measure of difference, of course; they are not looking at location or sequence comparisons, just what genes are brand spankin’ new and not shared at all with chimps). They found a few.

Many new genes, generated by diverse mechanisms including gene duplication, chimeric origin, retrotransposition, and de novo origin, are specifically expressed or function in the testes. Henrik Kaessmann hypothesized that the testis is a catalyst and crucible for the birth of new genes in animals. First, the testes is the most rapidly evolving organ due in part to its roles in sperm competition, sexual conflict, and reproductive isolation. Second, Henrik Kaessmann speculated that the chromatin state in spermatocytes and spermatids should facilitate the initial transcription of newly arisen genes. The reason for this is that there is widespread demethylation of CpG enriched promoter sequences and the presence of modified histones in spermatocytes and spermatids, causing an elevation of the levels of components of the transcriptional machinery, permitting promiscuous transcription of nonfunctional sequences, including de novo originated genes.

Behold my ball sack, noble repository of all that is precious and special and extraordinary and exceptional in mankind. How come the creationists never have time to praise the mighty testicle, and are always going on and on about sonnets and symphonies and such?

I am quite comfortable with my status as an animal. I have a lot of respect for other organisms, and I can also recognize traits that are particularly human. Why this puts creationists on edge is a mystery: I just blame it on their ignorance.

pro-lifeonly by lying about the science

Hemant Mehta let an anti-choice atheist romp about and make her secular pro-life argument

, but since he thinks it’s important to give a forum to bullshit but doesn’t think it’s important enough to criticize, I guess I have to. It’s by Kristine Kruszelnicki, president of Pro-Life Humanist, and we’ve dealt with her before; she’s the one who debated Matt Dillahunty in 2012, and lost miserably. She acknowledges that right at the beginning of her post, and then proceeds to make the same stupid argument.

Before we address the question of bodily autonomy in pregnancy, let’s meet the second player. What does science tell us that the preborn are? To be clear, science doesn’t define personhood. It never could. When I debated Matt Dillahunty on the issue of abortion at the 2012 Texas Freethought Convention, I’m afraid that as a first-time debater I really wasn’t clear enough on this point — and was consequently accused of trying to obtain rights from science. Science can’t tell us whether it’s wrong to rape women, torture children, enslave black people, or which physical traits should or should not matter when it comes to determining personhood. Science may be able to measure suffering in living creatures, but it can’t tell us why or if their suffering should matter.

Notice what she’s doing here. She recognizes that she totally got skewered on her claim that Science says abortion is wrong, so she’s nominally distancing herself from making moral claims with science. But guess what her very next sentence is?

However, science can tell us who among us belongs to the human species.

She’s doing it again. She’s claiming that science justifies her position.

She is at least aware that the right of women to autonomy is an extremely strong argument against her position — it’s how Dillahunty slammed her in the debate — and the entire post is about how she gets around that tricky problem of denying women control of their own bodies. Her solution? Simply decree by fiat, with the stamp of approval of her version of science, that the fetus and the woman have fully equal status as human beings, and that all discussion has to grant the fetus every privilege we do the woman.

If the fetus is not a human being with his/her own bodily rights, it’s true that infringing on a woman’s body by placing restrictions on her medical options is always a gross injustice and a violation. On the other hand, if we are talking about two human beings who should each be entitled to their own bodily rights, in the unique situation that is pregnancy, we aren’t justified in following the route of might-makes-right simply because we can.

At least this time, she didn’t sprinkle photos of bloody fetus parts in her post, and she avoided the most egregiously absurd elements of her position. This is my summary of what she said at the debate:

She made it clear that she opposes a whole gamut of basic rights: birth control methods that prevent implantation are wrong, because that’s just like strangling or starving a baby; no abortion in cases of rape or incest, because the baby doesn’t deserve punishment; she did allow for abortion in cases that threaten the life of the mother at times before fetal viability, simply because in that case two fully human lives would be lost.

She sounds like a very liberal Catholic atheist.

But that’s the entirety of her argument, both in that piece and on the pro-life atheist web site: the fetus is fully human from the moment of conception, and science says so.

When it comes to normal human reproduction, sperm and ovum merge to form a new whole. They cease to exist individually and become a new substance that is not the mother and not the father but a new body altogether, one that is also human and has the inherent capacity to develop through all stages of development.

When we talk about rights and personhood, we leave the realm of science for that of philosophy and ethics. History is ripe with examples of real biological human beings whose societies arbitrarily decided they didn’t qualify as equals, on account of criteria deemed morally relevant. At one point (and still, in many ways, today), it was skin color, gender, and ethnic background. Now, we can add to that list consciousness, sentience, and viability. We haven’t evolved so fast in 50 years as to be immune from tribalistic us vs. them thinking. If science defines a fetus as a biological member of our species, is it possible that our society is just as wrong in denying them personhood?

What happens when both a woman and her developing fetus are regarded as human beings entitled to personhood and bodily rights? Any way you cut it, their rights are always going to conflict (at least until womb transfers become a reality). So what’s the reasonable response? It could start by treating both parties at conflict as if they were equal human beings.

You get the idea. If she repeats that the conceptus becomes fully human at the instant of fertilization, and that science says so, over and over, we surely must be persuaded that she’s right, and we have to concede that she’s making an entirely secular argument, because SCIENCE. Unfortunately for her, she’s not actually using SCIENCE, but has mistaken BULLSHIT for science.

Let me tell you what science actually says about this subject.

Science has determined that development is a process of epigenesis; that is, that it involves a progressive unfolding and emergence of new attributes, not present at conception, that manifest gradually by interactions within the field of developing cells and with the external environment. The conceptus is not equal to the adult. It is not a preformed human requiring only time and growth to adulthood; developmental biologists are entirely aware of the distinction between proliferation and growth, and differentiation. So science actually says the opposite of what Kruszelnicki claims. It says that the fetus is distinct from the adult.

Of course, science also has to concede that because there is a continuum of transformation from conception to adulthood, it can’t draw an arbitrary line and say that at Time Point X, the fetus has acquired enough of the properties of the adult form that it should be now regarded as having all the rights of a member of society. That’s a matter for law and convention. But we already implicitly recognize that there is a pattern of change over time; children do not have all the same privileges as adults. Third trimester fetuses have fewer still. First trimester embryos? Even less. We all understand without even thinking about it that there is a progressive pattern to human development.

But what about this claim that science can tell us who among us belongs to the human species

?

First question I have is…which species concept are you using? There are a lot of them, you know; I daresay we might be able to find a few, that when inappropriately and too literally applied, would define away my status as a human, which simply wouldn’t do. There are also a lot of non-scientific or pseudo-scientific definitions of what constitutes a human that have been historically abused. Were the Nazis being scientific when they defined sub-species of humans and classed Jews, Gypsies, and Africans as something less than fully human? What, exactly, is Kruszelnicki’s “scientific” definition of human, that she’s using so definitively to declare a fetus as completely human?

She doesn’t say. She can’t say. She’s not applying a scientific test, but a traditional and colloquial one, which she’s then claiming by implication as synonymous with an unstated scientific definition. That’s dishonest and more than a little annoying.

Reading between the lines on her horrible little website, I’m guessing that she’s using a trivial and excessively reductive definition of human: it’s human by descent. The cells come from the division of human cells, so it is by definition not a monkey or a llama or a beetle cell, it’s a human cell.

Of course, that’s not enough: by that definition, sperm and eggs would be fully human, and women would be committing murder every time they menstruate, and men would be committing genocide every time they ejaculate. So she has a patch to work around that:

There is no such species as “sperm” or “ovum”. Sperm and ovum are not distinct unique organisms. They are in fact complex specialized cells belonging to the larger organism, namely the male and female from which they came. In other words, they are, like skin cells and blood cells, alive and bearing human DNA but nonetheless parts of another human being, even when mobile like the sperm.

There is no such species as “man” or “woman” either; we can always find some characteristic of an individual to distinguish them from a species (well hey, just the fact that they are an individual is enough). Her waffling about the status of sperm and ovum is ridiculous; I can give you species definitions that would recognize haploid gametes as fully human. If your restriction is simply that one is a complex, specialized cell belonging to the larger organism

, well gosh, the zygote fits that, too! A fertilized egg is not a generic human cell: it is incredibly specialized and complex.

I can’t help but notice that multicellularity isn’t part of her definition of “human”. Nor does it include any craniate characters, like having a notochord or a brain or branchial arches. There are a lot of scientific definitions of our species that the zygote fails!

If we’re going to emphasize the “not part of a human being” aspect of her fuzzy definition, then we have another problem. If you pooped this morning, that turd contained shed human epithelial cells, now swimming free. I could actually say, with full scientific accuracy, that that was a human turd. Why aren’t you giving it full legal protection?

She has an escape clause for that, too.

Sperm and ovum lose their individual identity and their function as sperm and ovum once they have merged. Instead of being parts carrying 23 chromosomes from two different human beings, the unification and merging of their chromosome pairs has now created a new whole with a new set of chromosomes and a cellular structure that now contains the inherent capacity to grow and develop itself through all stages of human development. This of course is something that neither sperm nor ovum parts had the inherent capacity to do on their own. It’s something that only whole human beings can do.

Oh. So here’s her full definition of a fully human being: it is a totipotent cell with the capacity to develop into a human being. Alas, her last sentence is wrong. Whole human beings cannot do that. It means I am not human, only a few small bits of me can aspire (in vain! I’m done with that) to someday fuse with another haploid cell and briefly become fully human, in the few days of happy cleavage before their cells become committed to specialized fates, which then are not fully human.

The only logical scientific conclusion one can make from Kruszelnicki’s hopeless definition is that blastocysts are fully human, but people are not.

Which actually doesn’t surprise me at all, and fits quite well with what I hear from the fetus-worshippers.

As I said before, there certainly are secular arguments for all kinds of nonsense — “secular” is not a synonym for “good”. We have to do more than simply accept arguments because they don’t mention gods, we also have to apply logical, reasonable philosophical and scientific filters to those secular arguments. The one obvious conclusion from any examination of these so-called “pro-life” arguments is that they are sloppy and dishonest, and not deserving of recognition by reasonable secular people.

Being atheist is not enough. One of the implications of an absence of gods is that revelation is invalid, and that we have to rely on reason and evidence to draw conclusions…and further, I would add, that we have to define values that we consistently and rationally apply, and we have to assess whether our methods appropriately serve those values. I choose to value the equality of a community of living, fully-born human beings, and when irrational superstitious attachment to status of a blastocyst compromises the autonomy and worth of members of that community, I choose to reject that belief. It helps quite a bit, though, that the “pro-life” position is so incoherent and anti-scientific.

Another take: even if you accept Kruszelnicki’s premise that a conceptus is “fully human” (I don’t), her argument doesn’t work and was dismantled over 40 years ago.

I was talking about sex and nothing but sex all last week in genetics, which is far less titillating than it sounds. My focus was entirely on operational genetics, that is, how autosomal inheritance vs inheritance of factors on sex chromosomes differ, and I only hinted at how sex is not inherited as a simple mendelian trait, as we’re always tempted to assume, but is actually the product of a whole elaborate chain of epistatic interactions. I’m always tempted in this class to go full-blown rabid developmental geneticist on them and do nothing but talk about interactions between genes, but I manage to restrain myself every time — we have a curriculum and a focus for this course, and it’s basic transmission genetics, and I struggle to get general concepts across before indulgence in my specific interests. Stick to the lesson plan! Try not to break everyone’s brain yet!

But a fellow can dream, right?

Anyway, before paring everything down to the reasonable content I can give in a third year course, I brush up on the literature and take notes and track down background and details that I won’t actually dump on the students (fellow professors know this phenomenon: you have to work to keep well ahead of the students, because they really don’t need to start thinking they’re smarter than you are). But I can dump my notes on you. You don’t have to take a test on it and get a good grade, and you won’t pester me about whether this will actually be on the test, and you won’t start crying if I overwhelm you with really cool stuff. (If any of my students run across this, no, the content of this article will not be on any test. Don’t panic. Go to grad school where this will all be much more relevant.)

Onward. Here’s my abbreviated summary of the epistatic interactions in making boys and girls.

The earliest step in gonad development is the formation of the urogenital ridge from intermediate mesoderm, a thickening on the outside of the mesonephros (early kidney), under the influence of transcription factors Emx2, Wt1 (Wilms tumor 1), Lhx9, and Sf1 (steroidogenic factor 1). Even in the earliest stages, multiple genes interact to generate the tissue! The urogenital ridge is going to form only the somatic tissue of the gonad; the actual germ cells (the cells that will form the gametes, sperm and ova) arise much, much earlier, in the epiblast of the embryo at a primitive streak stage, and then migrate through the mesenteries of the gut to populate the urogenital ridge independently, shortly after it forms.

At this point, this organ is called the bipotential gonad — it is identical in males and females. Two genes, Fgf9 and Wnt4, teeter in a balanced antagonistic relationship — Wnt4 suppresses Fgf9, and Fgf9 suppresses Wnt4 — in the bipotential gonad, and anything that might tip the balance between them will trigger development of one sex or the other. A mutation that breaks Fgf9, for instance, gives Wnt4 an edge, and the gonad will develop into an ovary; a mutation that breaks Wnt4 will let Fgf9 dominate the relationship, and the gonad will develop into a testis (with a note of caution: the changes will initiate differentiation into one gonad or the other, but there are other steps downstream that can also vary). These two molecules may be the universal regulators of the sex of the gonad in animals: fruit flies also use Fgf and Wnt genes to regulate development of their gonads.

But the key to the genetic symmetry-breaking of selecting Fgf9 and Wnt4 varies greatly in animals. Some use incubation temperature to bias expression one way or the other; birds have a poorly understood set of factors that may require heterodimerization between two different proteins produced on the Z and W chromosomes to induce ovaries; mammals have a unique gene, Sry, not found in other vertebrates, that is located on the Y chromosome and tilts the balance towards testis differentiation.

Sry may be unique to mammals, but it didn’t come out of nowhere. Sry contains a motif called the HMG (high mobility group) box, which is a conserved DNA binding domain. There are approximately 20 proteins related to Sry in humans, all given the name SOX, for SRY-related HMG box (I know, molecular biologists seem to be really reaching for acronyms nowadays). SOX genes are found in all eukaryotes, and seem to play important roles in cell and organ differentiation in insects, nematodes, and vertebrates. Sry is simply the member of the family that has been tagged to regulate gonad development in mammals.

If a copy of Sry is present in the organism, which is usually only the case in XY or male mammals, expression of the gene produces a DNA binding protein that has one primary target: a gene called SOX9 (they’re cousins!). In mice, Sry is switched on only transiently, long enough to activate SOX9, which then acts as a transcription factor for itself, maintaining expression of SOX9 for the life of the gonad. Humans keep Sry turned on permanently as well, but there’s no evidence yet that it actually does anything important after activating SOX9; it may be that human males neglect to hit the off switch.

SOX9 binds to a number of genes, among them, Fgf9. Remember Fgf9? The masculinizing factor in antagonism to the feminizing factor Wnt4? This tips the teeter-totter to favor expression of Fgf9 over Wnt4, leading to the differentiation of a testis from the bipotential gonad.

So far, then, we’ve got a nice little Rube Goldberg machine and an epistatic pathway. Sf1/Wt1 and other early genes induce the formation of a urogenital ridge and an ambiguous gonad; Sry upregulates Sox9 which upregulates Fgf9 which suppresses Wnt4, turning off the ovarian pathway and turning on the testis pathway.

But wait, we’re not done! Sry/SOX9 are expressed specifically in a subset of cells of the male gonad, the prospective Sertoli cells. If you recall your reproductive physiology, Sertoli cells are a kind of ‘nurse’ cell of the testis; they’re responsible for nourishing developing sperm cells. They also have signaling functions. The Sertoli cells produce AMH, or anti-Müllerian Hormone, which is responsible for causing the female ducts of the reproductive system to degenerate in males (if you don’t remember the difference between Müllerian and Wolffian and that array of tubes that get selected for survival in the different sexes, here’s a refresher). Defects in the AMH system lead to persistent female ducts: you get males with partial ovaries and undescended testicles. So just having the Sry chain is not enough, there are downstream genes that have to dismantle incipient female structures and promote mature properties of the gonad.

As the gonad differentiates, it also induces another set of cells, the embryonic Leydig cells. We have to distinguish embryonic Leydig cells, because they represent another transient population that will do their job in the embryo, then gradually die off to be replaced by a new population of adult Leydig cells at puberty. The primary function of Leydig cells is the production of testosterone and other androgens. The embryo gets a brief dose of testosterone early that initiates masculinization of various tissues, which then fades (fortunately; no beards and pubic hair for baby boys) to resurge in adolescence, triggering development of secondary sexual characteristics. Embryonic testosterone is the signal that maintains the Wolffian duct system. No testosterone, and the Wolffian ducts degenerate.

Just to complicate matters, while testosterone is the signal that regulates the male ducts, testosterone must be converted to dihydrotestosterone (DHT), the signal that regulates development of the external genitalia. Defects in the enzyme responsible for this conversion can lead to individuals with male internal plumbing, including testes, but female external genitalia. Sex isn’t all or nothing, but a whole series of switches!

By now, if you’re paying attention, you may have noticed a decidedly male bias in this description. I’ve been talking about a bipotential gonad that is flipped into a male mode by the presence of a single switch, and sometimes, especially in the older literature, you’ll find that development of the female gonad is treated as the default: ovaries are what you get if you lack the special magical trigger of the Y chromosome. This is not correct. The ovaries are also the product of an elaborate series of molecular decisions; I think it’s just that they Y chromosome and the Sry gene just provided a convenient genetic handle to break into the system, and really, scientists usually favor the easy tool to get in.

One key difference between the testis and ovary is the inclusion of germ cells. The testis simply doesn’t care; if the germ line, the precursors to sperm, is not present, the male gonad goes ahead and builds cords of Sertoli cells with Leydig cells differentiating in the interstitial space, makes the whole dang structure of the testicle, pumping out testosterone as if all is well, but contains no cells to make sperm — so it’s reproductively useless, but hormonally and physiologically active. The ovary is different. If no germ line populates it, the ovarian follicle cells (the homolog to the Sertoli cells) do not differentiate. If germ cells are lost from the tissue only later, the follicles degenerate.

Ovaries require a signal from the germ line to develop normally. One element of that signal seems to be factors associated with cells in meiosis. The female germ line cells are on a very strict meiotic clock, beginning the divisions to produce haploid egg cells in the embryo, even as they populate the gonad. These oocytes produce a signal, Figα (factor in germ line a) that recruits ovarian cells to produce follicles. The male gonad has to actively repress meiosis in the embryonic germ line to inhibit this signaling; male germ cells are restricted to only mitotic divisions until puberty.

Even before Figα signaling becomes important, there are other factors uniquely expressed in the prospective ovary that shape its development. In particular, Wnt4 induces the expression of another gene, Foxl2, that is critical for formation of the ovarian follicle. The pathways involved in ovarian development are not as well understood as those in testis development, but it’s quite clear that there is a chain of specific genetic/molecular interactions involved in the generation of both organs.

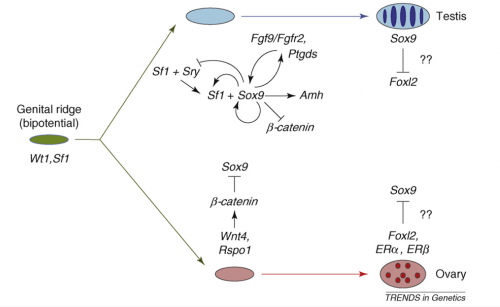

Wait, you say, you need a diagram! You can’t grasp all this without an illustration! Here’s a nice one: I particularly like that cauliflower-shaped explosion of looping arrows early in the testis pathway.

The molecular and genetic events in mammalian sex determination. The bipotential genital ridge is established by genes including Sf1 and Wt1, the early expression of which might also initiate that of Sox9 in both sexes. b-catenin can begin to accumulate as a response to Rspo1–Wnt4 signaling at this stage. In XX supporting cell precursors, b-catenin levels could accumulate sufficiently to repress SOX9 activity, either through direct protein interactions leading to mutual destruction, as seen during cartilage development, or by a direct effect on Sox9 transcription. However, in XY supporting cell precursors, increasing levels of SF1 activate Sry expression and then SRY, together with SF1, boosts Sox9 expression. Once SOX9 levels reach a critical threshold, several positive regulatory loops are initiated, including autoregulation of its own expression and formation of feed-forward loops via FGF9 or PGD2 signaling. If SRY activity is weak, low or late, it fails to boost Sox9 expression before b-catenin levels accumulate sufficiently to shut it down. At later stages, FOXL2 increases, which might help, perhaps in concert with ERs, to maintain granulosa (follicle) cell differentiation by repressing Sox9 expression. In the testis, SOX9 promotes the testis pathway, including Amh activation, and it also probably represses ovarian genes, including Wnt4 and Foxl2. However, any mechanism that increases Sox9 expression sufficiently will trigger Sertoli cell development, even in the absence of SRY.

So that’s what I didn’t tell my genetics students this time around. Maybe I’ll work it into my developmental biology course, instead.

Kim Y, Kobayashi A, Sekido R, DiNapoli L, Brennan J, Chaboissier MC, Poulat F, Behringer RR, Lovell-Badge R, Capel B. (2006) Fgf9 and Wnt4 act as antagonistic signals to regulate mammalian sex determination. PLoS Biol 4(6):e187

Ross AJ, Capel B. (2005) Signaling at the crossroads of gonad development. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 16(1):19-25.

Sekido R, Lovell-Badge R (2009) Sex determination and SRY: down to a wink and a nudge? Trends Genet. 25(1):19-29.

Sim H, Argentaro A, Harley VR (2008) Boys, girls and shuttling of SRY and SOX9. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 19(6):213-22.

Yao H H-C (2005) The pathway to femaleness: current knowledge on embryonic

development of the ovary. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 230:87–93.

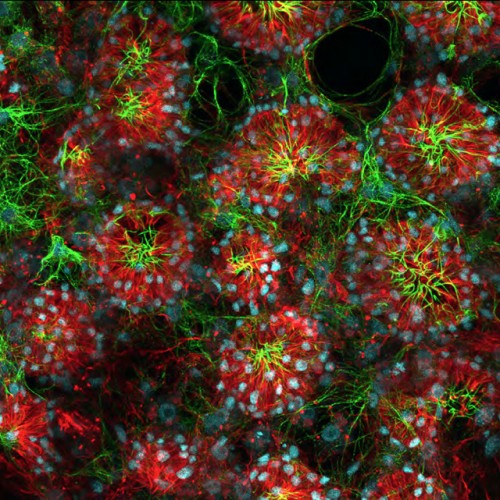

The image shows approximately 16 choanocyte chambers, each about 30 micrometers in diameter—about the size of a pollen grain. The green color marks the flagella—hair-like structures that pump the water. The red color marks the cytoskeleton, which includes a structure called the collar (not visible here) that captures the prey. The light-blue regions mark the nuclei of individual choanocytes.

Can you generate the illusion that your mind has left your body? This woman can.

After a class on out-of-body experiences, a psychology graduate student at the University of Ottawa came forward to researchers to say that she could have these voluntarily, usually before sleep. “She appeared surprised that not everyone could experience this,” wrote the scientists in a study describing the case, published in February in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

So what does the modern researcher do when someone has a weird perceptual sensation? Stick their head in an MRI and look at what’s happening.

To better understand what was going on, the researchers conducted a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study of her brain. They found that it surprisingly involved a “strong deactivation of the visual cortex.” Instead, the experience “activated the left side of several areas associated with kinesthetic imagery,” such as mental representations of bodily movement.

Her experience, the scientists wrote, “really was a novel one.” But just maybe, not as novel as previously thought. If you are capable of floating out of your body, don’t keep it to yourself!

OK, I won’t. I used to be able to do that. When I was roughly 5 to 7 years old, and with declining frequency in years afterwards, I experienced this phenomenon routinely, and it was exactly as described. As I was drifting off to sleep, I’d have this peculiar sensation of heightened kinesthesia — I’d be acutely aware of my body, where every limb was, and I’d also lose my other senses — my hearing was muffled, with a kind of low hum, and I wouldn’t be able to see anything. But at the same time, I also had an exaggerated consciousness of objects around me, so I’d literally feel like a small boy with an awareness expanding to fill the room, losing the disconnect between self and other. And then I’d fall asleep.

Even as a child, though, I didn’t describe it to myself as floating outside myself; I called them my “big head dreams”, because of the way my awareness of space increased. I might have been annoyed at my bedtime, but I didn’t will myself to float out into the living room and watch TV, ghostlike, with my parents. I saw it as an odd shift in the focus of my attention as I drifted off to sleep, a kind of hallucination, nothing more.

I enjoyed the sensation and would voluntarily succumb to it, but it occurred less often as I got older. Probably the last time I experienced it was in my teens, but I still vividly recall what it felt like.

It was not out-of-body travel. Rebecca Watson has a reply to the article, and clarifies for the gullible that no, scientists aren’t studying out-of-body experiences, they’re looking at sensory processing and mental imagery.

The word “hallucination” appears ten times in the case study yet zero times in the Popular Science article. Because of this, a naive person who reads the PopSci article but not the original paper may walk away with the belief that the brain scans show what happens when a person actually leaves their body, as opposed to showing what happens when a person feels as though they are leaving their body. Again, the difference seems small but is actually quite large: the former describes a study that would be at home on an episode of Coast to Coast or Fringe or those episodes of Family Matters where Urkel did science experiments, and the latter would be at home in a scientific journal to be used as the basis for further study and experimentation.

Move along, it’s all mundane brain science. No spirits involved.

The cows. Thousands of years of sneaky deviousness — do not fear Skynet, it’s the time when the cows achieve full sentience (if they haven’t already) and rise up against us that you should be dreading.

Sometimes those are good descriptors. I read a happy story for a change this morning: it’s about Arunachalam Muruganantham, an Indian man who embarked on a long crusade to make…sanitary napkins. Perhaps you laugh. Perhaps you get a little cranky at a guy who rushes in to meddle in women’s concerns. And there’s some good reason to feel that way: he starts out with embarrassing levels of ignorance.

He fashioned a sanitary pad out of cotton and gave it to Shanthi [his wife], demanding immediate feedback. She said he’d have to wait for some time – only then did he realise that periods were monthly. “I can’t wait a month for each feedback, it’ll take two decades!” He needed more volunteers.

And then a man who didn’t realize until then that menstrual periods were monthly dedicated himself to years of tinkering and testing to build a machine to manufacture sanitary napkins, which just sounds perversely fanatical and obsessive. But it turns out to be a serious problem for poor women.

Women who do use cloths are often too embarrassed to dry them in the sun, which means they don’t get disinfected. Approximately 70% of all reproductive diseases in India are caused by poor menstrual hygiene – it can also affect maternal mortality.

So Muruganantham set out to teach himself everything about making napkins, and examining and testing used menstrual pads. His wife left him. He was regarded as a sick pariah in his town — the disgusting guy who plays with menstrual blood. He was going up against traditional taboos and public squeamishness.

But he succeeded! He designed and built simple machines that take cotton and cellulose at one end and churn out disposable sanitary napkins — and it was relatively cheap, easy to maintain, and could be distributed to rural India where the women themselves could make the necessaries. And then we learn about his philosophy…

Muruganantham seemed set for fame and fortune, but he was not interested in profit. “Imagine, I got patent rights to the only machine in the world to make low-cost sanitary napkins – a hot-cake product,” he says. “Anyone with an MBA would immediately accumulate the maximum money. But I did not want to. Why? Because from childhood I know no human being died because of poverty – everything happens because of ignorance.”

He believes that big business is parasitic, like a mosquito, whereas he prefers the lighter touch, like that of a butterfly. “A butterfly can suck honey from the flower without damaging it,” he says.

Oh my god, an idealist. I thought they were all extinct! And such a fine beautiful specimen, too! I’m going to steal that metaphor, as well, just because it is so lovely.

Most of Muruganantham’s clients are NGOs and women’s self-help groups. A manual machine costs around 75,000 Indian rupees (£723) – a semi-automated machine costs more. Each machine converts 3,000 women to pads, and provides employment for 10 women. They can produce 200-250 pads a day which sell for an average of about 2.5 rupees (£0.025) each.

Women choose their own brand-name for their range of sanitary pads, so there is no over-arching brand – it is “by the women, for the women, and to the women”.

And my heart grew two sizes that day.