So I wrote this short essay for the Washington Post, and it’s been interesting reaching a whole different audience. It’s not an audience that is increasing my esteem for the human race, unfortunately, but it’s been…different. My twitter stream has been flooded by irate Christians, which is fun, but most of their responses are rather familiar.

Here’s one common flavor: patronizing Christian sympathy.

Berth2020 @berth2020

@washingtonpost @pzmyers you need to work on being kind to others. . I’m sorry you’ve been hurt.

I haven’t been hurt, and I don’t consider wallowing in lies as you do to be “kind”.

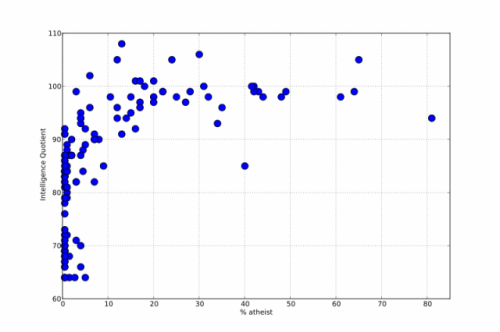

Then there’s the usual stereotyping of atheists as amoral monsters.

romesh sharma1949 @romesh1949

@washingtonpost @pzmyers Atheist,a man who is answerable to None, free from all bonds , will behave like an animal 99.99% or saint 00.01%

Right, Mr Made-Up-Statistics. So the prisons must be like 99.99% atheist?

Then, of course, there are the excuses.

Christopher Dull @PaEvengelist

@jeremydavidpare @DavisRBr @washingtonpost @pzmyers One reason for unanswered prayer is God does not here the prayers of unrepentant sinners

Interesting. So if you pray, and you don’t get what you want, you must be one of those unrepentant sinners? What are the other reasons?

But the most common complaint, the one that seems to be winning the votes right now, surprises me a bit.

Jeremy @jeremydavidpare

@pzmyers almost nothing you said in that article even remotely resembles anything Christian’s believe or practice… #misinformedatheist

This particular guy sent out a dozen tweets calling for his buddies to refute me; another fellow repeatedly demanded that the Washington Post allow him equal time to rebut my inaccuracies. I haven’t told the truth about Christianity!

What? Let me remind you of what my essay was about: I talked about the baggage we atheists have freed ourselves from, and I gave very general examples, stuff that is widely true of most of the diverse Christian sects in this country. Here’s a shorter version of what I mentioned.

1. No church and no sermons.

The practice of Christianity in this country certainly does involve church attendance, and it’s customary in most faiths (with exceptions, like the Quakers) to have a priest lecture you on proper behavior and beliefs at these events.

2. No heaven or hell, no bribes or threats.

Again, most Christian sects have notions of reward and punishment in an afterlife.

3. No prayers.

Every version of Christianity I’ve experienced is prayer-soaked — a combination of entreaties and worship of an invisible deity. How can anyone deny this?

4. No guilt about defying a deity.

A common Christian command is to OBEY god, one and only one god. You will be punished if you disobey. Of course there’s a burden of guilt for failure to do as the priest tells you to do!

5. No power from above, no hierarchies.

With rare exceptions (again, Quakers), most Christian sects lay out a very specific hierarchy of power and responsibilities — with Catholicism the most obvious, with power from God to Pope to Cardinals to Bishops to Priests to the laity.

6. No false consolation at death.

Another really common feature of Christianity: just go to a funeral. Look at the political cartoons after a famous person dies. “They’re in a better place,” everyone says. Wrong, say I, they’re dead and lost to us forever, and mourning is the right and proper response.

Nothing I said was in the slightest bit inaccurate; these are general properties of the practice of religion in this country. So what could they possibly argue that I was wrong about?

I have a guess. They’re going to deliver some pious hokum about the True Meaning of Faith™, which will be some pablum about redemption by the torture/execution of a fanatical Jewish preacher in the first century CE, and how the important part of Christianity is love and fellowship and spreading the gospel of our Lord, Jesus Christ, and the story of our immortal, eternal god who died and bounced back a day and a half later, since he was able to perform a Resurrection spell (but unfortunately, was unable to Cure Light Wounds so he had to walk around with holes in his hands).

Which means I forgot to include an important piece of baggage we atheists don’t have to haul around.

7. We don’t have to pretend to believe in obvious bullshit.