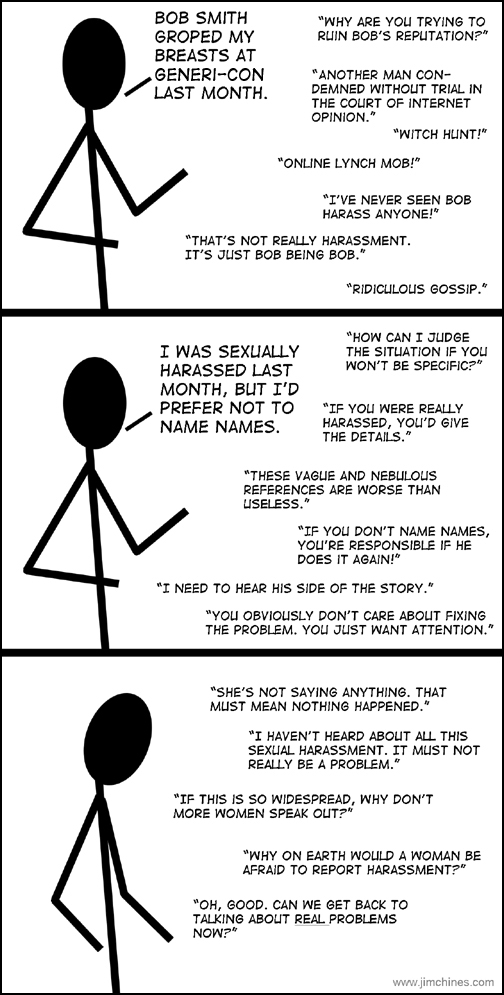

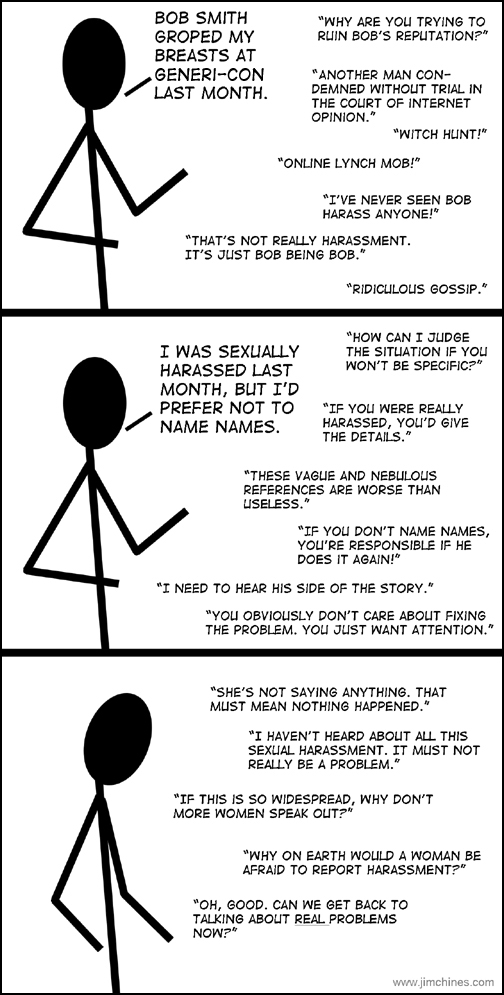

via Jim C. Hines

via Jim C. Hines

I’m dyin’ here, people. It’s like people trust me or something.

So I’ve been given this rather…explosive…information. It’s a direct report of unethical behavior by a big name in the skeptical community (yeah, like that hasn’t been happening a lot lately), and it’s straight from the victim’s mouth. And it’s bad. Really bad.

She’s torn up about it. It’s been a few years, so no law agency is going to do anything about it now; she reported it to an organization at the time, and it was dismissed. Swept under the rug. Ignored. I can imagine her sense of futility. She’s also afraid that the person who assaulted her before could try to hurt her again.

But at the same time, she doesn’t want this to happen to anyone else, so she’d like to get the word out there. So she hands the information to me. Oh, thanks.

Now I’ve been sitting here trying to resolve my dilemma — to reveal it or not — and goddamn it, what’s dominating my head isn’t the consequences, but the question of what is the right thing to do. Do I stand up for the one who has no recourse, no way out, no other option to help others, or do I shelter the powerful big name guy from an accusation I can’t personally vouch for, except to say that I know the author, and that she’s not trying to acquire notoriety (she wants her name kept out of it)?

I’ve got to do what I’ve got to do, I can do no other. I will again emphasize, though, that I have no personal, direct evidence that the event occurred as described; all I can say is that the author is known to me, and she has also been vouched for by one other person I trust. The author is not threatening her putative assailant with any action, but is solely concerned that other women be aware of his behavior. The only reason she has given me this information is that she has no other way to act.

With that, I cast this grenade away from me…

At a conference, Mr. Shermer coerced me into a position where I could not consent, and then had sex with me. I can’t give more details than that, as it would reveal my identity, and I am very scared that he will come after me in some way. But I wanted to share this story in case it helps anyone else ward off a similar situation from happening. I reached out to one organization that was involved in the event at which I was raped, and they refused to take my concerns seriously. Ever since, I’ve heard stories about him doing things (5 different people have directly told me they did the same to them) and wanted to just say something and warn people, and I didn’t know how. I hope this protects someone.

Boom.

Further corroboration: a witness has come forward. This person has asked to remain anonymous too, but I will say they’re someone who doesn’t particularly like me — so no accusations of fannishness, OK?

The anonymous woman who wrote to you is known to me, and in fact I was in her presence immediately after said incident (she was extremely distraught), and when she told the management of the conference (some time later).

Women are still writing into me with their personal stories. This one isn’t so awful, but it’s mainly illustrative of his tactics…there’s nothing here that would form the basis of any kind of serious complaint, but most importantly, I think, it tells you exactly what kind of behavior to watch out for with him.

Michael Shermer was the guest of honor at an atheist event I attended in Fall 2006; I was on the Board of the group who hosted it. It’s a very short story: I got my book signed, then at the post-speech party, Shermer chatted with me at great length while refilling my wine glass repeatedly. I lost count of how many drinks I had. He was flirting with me and I am non-confrontational and unwilling to be rude, so I just laughed it off. He made sure my wine glass stayed full.

And that’s the entirety of my story: Michael Shermer helped get me drunker than I normally get, and was a bit flirty. I can’t recall the details because I was intoxicated. I don’t remember how I left, but I am told that a friend took me away from the situation and home from the party. Note, I’d never gotten drunk at any atheist event before; I was humiliated by having gotten so drunk and even more ashamed that my friends had to cart me off before anything happened to me.

But I had a bad taste in my mouth about Shermer’s flirtatiousness, because I’m married, and I thought he was kind of a pig. I didn’t even keep his signed book, I didn’t want it near me.

Over the years as rumors have flown about atheist women warning each other about a lecherous author/speaker, I thought of all the authors and speakers I had met during my time as an atheist activist, and I guessed that Shermer was the one being warned against.

Now there are tweets and blogs about his sexually inappropriate behavior as well as his fondness for getting chicks drunk, so I feel quite less alone. I don’t think he realizes he is doing anything wrong. Men who behave inappropriately sexually never think they are doing anything wrong.

I have mixed feelings about your grenade-dropping. I have heard arguments both for and against what you did. Whether or not I agree with it, I just want to say that the accusations against Shermer match up with my personal experience with him, insofar as he seemed hellbent on helping me get drunk, and was very flirty with me. Take it for what you will. I believe the accusers.

When I heard that Steven Pinker had written a new piece decrying the accusations of scientism, I was anxious to read it. “Scientism” is a blunt instrument that gets swung in my direction often enough; I consider it entirely inappropriate in almost every case I hear it used.

Here’s the thing: when I say that there is no evidence for a god, that there’s no sign that there is a single specific thing this imagined being has done, I am not unfairly asking people to adopt the protocols of science — I am expecting to judge by their own standards and expectations. They are praying to Jesus in the expectation of a reward, not as, for instance, an exercise in artistic expression, so it is perfectly legitimate to point out they aren’t getting anything, and their concept of Jesus contradicts their own expectations. When I mock Karen Armstrong’s goofy deepities praising her nebulous cosmic being, I’m not saying she’s wrong because her god won’t fit in a test tube or grow in a petri dish, but because she’s doing bad philosophy and reasoning poorly — disciplines which are greater than and more universal than science.

Science is a fantastic tool (our only tool, actually) for probing material realities. Respect it for what it is. But please, also recognize that there’s more to the human experience than measurement and the acquisition of knowledge about physical processes, and that science is a relatively recent and revolutionary way of thinking, but not the only one — and that humans lived and thrived and progressed for thousands of years (and many still do, even within our technological culture!) without even the concept of science.

Scientism is the idea that only science is the proper mode of human thought, and in particular, a blinkered, narrow notion that every human advance is the product of scientific, rational, empirical thinking. Much as I love science, and am personally a committed practitioner who also has a hard time shaking myself out of this path (I find scientific thinking very natural), I’ve got enough breadth in my education and current experience to recognize that there are other ways of progressing. Notice that I don’t use the phrase “ways of knowing” here — I have a rigorous enough expectation of what knowledge represents to reject other claims of knowledge outside of the empirical collection of information.

It’s the curse of teaching at a liberal arts university and rubbing elbows with people in the arts and humanities all the time.

Which is why I was disappointed with Pinker’s article. I expected two things: an explanation that science is one valid path to knowledge with wide applicability, so simply applying science is not the same as scientism; and an acknowledgment that other disciplines have made significant contributions to human well-being, and therefore we should not pretend to be all-encompassing.

And then I read the first couple of paragraphs of his essay, and was aghast. This was unbelievable hubris; he actually is practicing scientism!

The great thinkers of the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment were scientists. Not only did many of them contribute to mathematics, physics, and physiology, but all of them were avid theorists in the sciences of human nature. They were cognitive neuroscientists, who tried to explain thought and emotion in terms of physical mechanisms of the nervous system. They were evolutionary psychologists, who speculated on life in a state of nature and on animal instincts that are “infused into our bosoms.” And they were social psychologists, who wrote of the moral sentiments that draw us together, the selfish passions that inflame us, and the foibles of shortsightedness that frustrate our best-laid plans.

These thinkers—Descartes, Spinoza, Hobbes, Locke, Hume, Rousseau, Leibniz, Kant, Smith—are all the more remarkable for having crafted their ideas in the absence of formal theory and empirical data. The mathematical theories of information, computation, and games had yet to be invented. The words “neuron,” “hormone,” and “gene” meant nothing to them. When reading these thinkers, I often long to travel back in time and offer them some bit of twenty-first-century freshman science that would fill a gap in their arguments or guide them around a stumbling block. What would these Fausts have given for such knowledge? What could they have done with it?

Hooooly craaaaaap.

Look, there’s some reasonable stuff deeper in, but that opening…could he possibly have been more arrogant, patronizing, and ahistorical? Not only is he appropriating philosophers into the fold of science, but worse, he’s placing them in his favored disciplines of cognitive neuroscience, evolutionary psychology, and social psychology. Does the man ever step outside of his office building on the Harvard campus?

Descartes and Hume were not evolutionary psychologists. He’s doing great violence to the intellectual contributions of those men — and further, he’s turning evolutionary psychology into an amorphous and meaningless grab-bag which can swallow up every thought in the world. The latter, at least, is a common practice within evo psych, but please. Hume was a philosopher. He was not a psychologist, a biologist, or a chemist. He was not doing science, even though he thought a lot about science.

I probably know more about the biological side of how the brain functions than Pinker does, with my background in neuroscience, cell biology, and molecular biology. But I have no illusions. If I could travel in time to visit Hume or Spinoza, I might be able to deliver the occasional enlightening fact that they would find interesting, but most of my knowledge would be irrelevant to their concerns, while their ideas would have broader applicability and would enlighten me. When I imagine visiting these great contributors to the philosophy of science (Hume and Bacon would be at the top of my list), I see myself as a supplicant, hoping to learn more, not as the font of wisdom come to deliver them from their errors. Alright, I might argue some with them, but Jesus…they have their own domains of understanding in which they are acknowledged masters, domains in which I am only a dabbler.

He’s committing the fallacy of progress and scientism. There is no denying that we have better knowledge of science and engineering now, but that does not mean that we’re universally better, smarter, wiser, and more informed about everything. What I know would be utterly useless to a native hunter in New Guinea, or to an 18th century philosopher; it’s useful within a specific context, in a narrow subdomain of a 21st technological society. I think Pinker’s fantasy is not one of informing a knowledgeable person, but of imposing the imagined authority of a modern science on someone from a less technologically advanced culture.

It’s actually an encounter I’d love to see happen. I don’t think evolutionary psychology would hold up at all under the inquisitory scrutiny of Hume.

I tried to put myself in the place of one of my colleagues outside the sciences reading that essay, and when I did that, I choked on the title: “Science Is Not Your Enemy: An impassioned plea to neglected novelists, embattled professors, and tenure-less historians”. How condescending! I know there are a few odd professors out there who have some bizarre ideas about science — they’re as ignorant of science as Pinker seems to be of the humanities — but the majority of the people I talk to who are professors of English or Philosophy or Art or whatever do not have the idea at all that science is an enemy. They see it as a complementary discipline that’s prone to a kind of overweening imperialism. I get that: I feel the same way when I see physicists condescend to mere biologists. We’re just a subset of physics, don’t you know, and don’t really have an independent history, a novel perspective and a deep understanding of a very different set of problems than the ones physicists study.

Just as biologists freely use the tools of physics, scholars in the humanities will use the tools of science where appropriate and helpful. They do not therefore bow down in fealty to the one true intellectual discipline, great Science. I have never known a one to reject rigor, analysis, data collection, or statistics and measurement…although they can get rather pissy if you try to tell them that the basic tools of the academic are copyright Science.

And, dear god, Pinker tells this ridiculous and offensive anecdote:

Several university presidents and provosts have lamented to me that when a scientist comes into their office, it’s to announce some exciting new research opportunity and demand the resources to pursue it. When a humanities scholar drops by, it’s to plead for respect for the way things have always been done.

Oh, fucking nonsense. Humanities scholars are just as interested in making new discoveries as evolutionary psychologists, and are just as enthusiastic about pursuing ideas. What I’ve seen is that university presidents and provosts are typically completely clueless about what scholars do — does anyone really believe Larry Summers had the slightest appreciation of the virtues of knowledge? — so it’s bizarre in the first place to cite the opinions of our administrative bureaucrats. What this anecdote actually translates to is that a scientist stops by with an idea that needs funding that will lead to big grants and possible patent opportunities, and president’s brain goes KA-CHING; humanities scholar stops by with a great insight about French Impressionism or the history of the Spanish Civil War, asks for travel funds (or more likely, pennies for paper and ink), and president’s brain fizzles and can’t figure out how this will bring in a million dollar NIH grant, so what good is it? Why can’t this deadwood get with it and do something with cancer genes or clinical trials?

Perhaps I would have been more receptive to Pinker’s message if I hadn’t sat through a meeting this afternoon with an administrator from the big campus in Minneapolis/St Paul. It was a strange meeting; he’s clearly got grand plans that are of benefit to us, he’s supportive of science, but this was a meeting attended by research faculty in all of the campus disciplines: science, humanities, social sciences, the arts. It was odd to hear all the talk that was focused on a purely science-oriented strategy, when there were all these people around me who are doing research that doesn’t involve equipment grants, NIH funding, and patent opportunities. One of my colleagues spoke up and mentioned that he seemed to be treating the humanities as supporting infrastructure for biology or chemistry, rather than as a respectable scholarly endeavor in its own right.

I was feeling the same way. I’m a biologist, but I do biology because it’s beautiful and I love it and it inspires students. This was all about doing science because it brings in big money to the university. What was in my head was this quote from D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson:

“The harmony of the world is made manifest in Form and Number, and the heart and soul and all the poetry of Natural Philosophy are embodied in the concept of mathematical beauty.”

Substitute “Science” for “Natural Philosophy” (a perfectly reasonable replacement, given what Thompson understood the phrase to mean), and you’ve got a rebuttal to scientism. Heart, soul, poetry, beauty are not grist for the analytical mill of science, but they really are the core, and if you don’t appreciate that, the breadth of your education is lacking.

I’ve been harsh to Pinker’s claims, but you probably shouldn’t see it as a disagreement. Read further into his essay, if you can bear it, and you’ll discover that rather than rejecting scientism he proudly claims it for his own. To accuse him of scientism is no insult, then; it’s only the term for what he happily embraces.

I don’t think I’ll join him in that isolation tank, though.

Dammit. It used to be that I was the guy with a reputation for vehemence, but I’ve got nothin’ on this.

I confess — I sometimes find Stephen Colbert’s schtick wearing. But other times…whoa, this is beautiful. He got stood up by a musical guest, Daft Punk, so he complains about it bitterly and hilariously.

Ooops, stuffed it below the fold because the stupid videos are on autoplay. Why do people configure their videos that way? Are they just incompetent?

If you’re one of those privileged people who has an iPad, and if you’re also one of those quality people who appreciates the brilliant Robin Ince, take a look at the The Incomplete Map of the Cosmic Genome for iPad on the iTunes App Store.

Now you might be wondering what it is. I’ve got it, and I still am. It’s one of those thingumabobs that fits words like “eclectic” and “ooooh” and “oh, what a colossal time sink”. It’s a…well, it’s a…OK, it’s a miscellany of enthusiastic science presentations.

It’s also kind of like a good science programming channel (you know how those have vanished from cable) with Infrequent/Mild Profanity or Crude Humour. If that helps. Download it yourself and try it and explain it to me.

They keep stuffing things in there, and you open it up and tap on something and there’s Brian Cox telling you how wonderful the universe is, or Steve Jones talking about Alfred Russel Wallace, or…ooh, an appreciation of Jacob Bronowski. I didn’t see that last time I browsed it. Excuse me, I have to vanish for a little while.

I think the cork has been popped, and we can expect more stories to come flooding out now. Karen Stollznow spoke out, and now, Carrie Poppy has sent me her story. Carrie abruptly left the JREF a while back, and would not speak publicly about her reasons for leaving, but now, with Stollznow’s example, she tells all.

I do have her permission to publish this account.

Dear PZ,

Thanks for you recent coverage of Karen Stollznow’s ongoing harassment in her workplace and the assaults she says she endured at skeptical conferences. I have been in close contact with Dr. Stollznow in recent months, and have confirmed and clarified various details with her that I think you will find very relevant to your blog. Dr. Stollznow has given her blessing for me to send these details to you, as well. I am CCing Dr. Stollznow, too.

Most of these details have to do with my former employer, the James Randi Educational Foundation (JREF). I left the JREF in November 2012, after only six months there. I quit in protest of a number of ethical issues; foremost was what I perceived as the president, D.J. Grothe’s constant duplicity, dishonesty, and manipulation. I did not believe he had the best interests of the organization or community he “served” at heart. This was difficult for me, as Mr. Grothe and I had been friends prior to my joining the staff. Yet, it was very clear by the time I left that my continuing to work there was being complicit in unethical behavior, including the kind of behavior of which Dr. Stollznow is now on the receiving end. I have not spoken very publicly about my experience at the JREF, for various personal reasons, but one of them was cowardice. I simply didn’t want to have to defend myself, relive the six months of misery I’d already endured, or be branded as on one “side” or another of an ongoing debate. I simply wanted to move on. But as Dr. Stollznow’s story, and others, came to light, I knew I couldn’t keep quiet any longer. Dr. Stollznow’s experience is too much like so many women’s in skepticism.

Here are the most relevant facts:

1. Dr. Stollznow says that she was assaulted at the James Randi Educational Foundation’s (JREF) annual conference, The Amazing Meeting (TAM) on three separate occasions. Dr. Stollznow is a research fellow for the JREF, and is a respected speaker at TAM. The person who she says assaulted her is Ben Radford, another speaker at TAM and a long-time ally of the JREF’s. I am not speaking to the legal validity of these claims, as I have no legal expertise on the matter, but I believe Karen’s account, given the information she’s relayed to me in private, which I won’t recount here.

2. Dr. Stollznow says she made these alleged assaults known to JREF president D.J. Grothe several months ago, but according to Karen, he declined to do anything about the matter.

3. CFI told Dr. Stollznow that they would only be reprimanding their employee for his behavior. Dr. Stollznow let Mr. Grothe know that she felt her harassment and assault were being treated as nothing more than a grievance among friends, and Grothe responded, ” I am happy to learn from you that the CFI has responded to your complaints with the seriousness they deserve.” (see attachment 1).

4. Dr. Stollznow requested that Mr. Grothe assure her that her alleged assailant would not be at future JREF events, for her safety and the safety of others at future events. Mr. Grothe declined to ban the speaker, saying, “there are at present no such plans” to have Mr. Radford speak at a JREF event, more than a year before the next TAM, and well before speaking engagements are secured (see attachment 2).

5. Dr. Stollznow approached the JREF board, asking them to intervene in Mr. Grothe’s bizarre behavior, and make a commitment not to have the speaker in question at future JREF events. Their response: “JREF does not and will not have a blacklist” (see attachment 3).

I wish I could say that I found Dr. Stollznow’s story shocking or unprecedented, but I cannot. In my time at the JREF, I witnessed continuous unethical behavior, much of which I reported to the Board of Directors. I was assured on more than one occasion by James Randi that D.J. Grothe would be fired (I hear Randi denies this now, though he repeatedly promised it to another staff member as well, and that staff member and I represented the entirety of JREF full-time staff other than D.J. and his husband, Thomas), but after several months of waiting and being asked to wait, it became clear that D.J. was not going to be fired. The list of problems that I sent to the board was so long that my pasting it here would be comical at best, but it is relevant to note that although I didn’t list it, Mr. Grothe’s prejudice toward women was one undeniable factor. My predecessor, Sadie Crabtree, had warned me about D.J.’s misogyny and disrespect for women coworkers (she even advised me not to take the position, due to this issue), but I thought myself strong enough to endure it. I underestimated the degree to which such constant mistreatment can beat a person down. As I mentioned, I only lasted six months.

The final straw, for me, was that Mr. Grothe attempted to remove me as a speaker from the Women in Secularism 2 conference, going above my head (and Melody Hensley’s head) to her male boss, Ron Lindsay, and telling him that it would be bad for the JREF’s image if I attended a “feminist conference.” In defending his actions to me, D.J. told me he didn’t trust me to handle the event, saying I would be asked if he was a sexist (an unanswerable question in his mind, apparently) and that I might break down in tears crying about my own sexual assault, if the issue of rape arose. I was given no credit for the fact that I am a professional spokesperson with almost a decade of experience, that I have a successful skeptical podcast, am a published author, and that my personal assault experience makes my opinions on assault more relevant, not less. To him, I was a hysterical woman, nothing more.

I am not going to say more on this on public forums– No doubt, people will press me for evidence and take the side of the organization and individual in power. When it comes to institutional power, the leaders are innocent until proven guilty. What so few realize is the converse of this: the victims are guilty until proven innocent.

I don’t want to send this email. I don’t want to go public with my story. I don’t want to receive the emails or the tweets or the phone calls. But fuck it. It’s the right thing to do.

Thanks for taking the time to read about my experience. And please, let’s all stick by Karen and ask the JREF to (1) install new leadership, and (2) protect their attendees and respect their research fellow by not allowing her alleged assailant to attend future events.

Best,

Carrie

cc: Dr. Karen Stollznow

Attachment 1

From: D.J. Grothe

Date: Fri, Jul 5, 2013 at 2:20 PM

Subject: Re: CFI Investigation

To: Karen StollznowThank you Karen for informing me of this email, but you certainly were under no obligation to do so. I appreciate how difficult the situation must have been for you, and I am happy to learn from you that the CFI has responded to your complaints with the seriousness they deserve. Please let me know if there is anything I can do for you personally, or the JREF might assist you in any way.

See you in less than a week in Vegas. And talk soon.. D.J.

On Jul 4, 2013, at 4:59 PM, Karen Stollznow

wrote:

> Hi D.J.,

>

> I wanted to update you with the results of CFI’s investigation into my complaints regarding Ben Radford.

>

> Please see attached the letter they sent to me. I think they have trivialized and minimized my complaints and they have also made some factual errors. My complaints go back to 2009, not 2012, and I don’t know what Barry means by “retaliation”. They won’t give me a copy of the report. I will be taking this further.

>

> At any rate, they have admitted that Ben has behaved inappropriately at conferences and harassed me with unwanted correspondence. I think this is info you need to know.

> All the best,

>

> Karen.

Attachment 2

From: D.J. Grothe

Date: Fri, Jul 5, 2013 at 3:27 PM

Subject: Re: CFI Investigation

To: Karen StollznowI did read your email carefully, Karen. And I do know that you were unhappy with aspects of CFI’s response, including the inaccuracy on time periods, etc. as you mentioned in your email to me.

And no, you were under no obligation to send me CFI’s letter that they sent to you. Reporting to me developments in general terms, without detailing specifics of CFI’s HR decisions regarding their employee, would have sufficed if you wanted to let me know if matter was resolving, developing, or changing, etc.. And I certainly don’t mind that you shared it, indeed, as I said, I do sincerely appreciate your letting me know of these developments. This is for a number of reasons not the least important of which is because as a conference organizer I certainly do not want to involve speakers who harass or otherwise abuse other speakers or attendees or who engage in other misconduct or disrespect of personal boundaries.

As for incidents happening TAM proper, I know that you never made specific complaints at those times, instead later focusing on seeking CFI action, for the understandable reasons you originally communicated; that CFI is his employer. And that you also discussed these matters regarding Ben Radford with our consultant and with me personally by email. And you did notify us clearly that if Ben Radford were to be on our program, that you would not. As you know, he is not on the program at TAM, and we are very happy that you are.

Actions JREF took after the phone meetings and emails with you include: keeping a detailed record of your communications and concerns on file for future reference (this is important not just in an HR sense, but also if there are other patterns of behavior that would need to be corroborated because of further developments), our consultant on HR matters having phone meetings and emails with you, and also that we clearly reiterated directly to Ben (as well as other past TAM speakers) JREF’s policies regarding misconduct at our public events. This is in addition to JREF’s internal HR policies for its employees that prohibit sexual harassment of any kind in the workplace.

Since Ben Radford is not an employee of the JREF, we cannot reprimand him like his employer could, but we have told him that on our watch he is to have no contact with you whatsoever, should he ever be involved with the JREF in the future (for the record there are at present no such plans). Obviously, this issue is moot as regards this year’s conference for reasons we have discussed a couple of times already.

Again, please let me know if there’s anything further I can do personally, or that JREF can do organizationally, to assist you, or to help you with CFI if you, or as you, pursue the matter further.

See you next week Karen. I really look forward to it. D.J.

Attachment 3

On Jul 5, 2013, at 1:41 PM, Karen Stollznow

wrote: Hey D.J., Of course I had an obligation to send you the letter – several incidents occurred at TAM. You had to be made aware of this so you can protect conference attendees in the future. Now we have a record that you know about this.

I don’t think you read my email carefully though because I’m not happy with CFI’s blase response. As I said, I’m taking this matter further with them.

Karen.

From: Chip Denman

Date: July 24, 2013, 5:17:19 PM MDT

To: Karen Stollznow

Subject: Re: A matter for the attention of the JREF BoardDear Karen —

Thank you for contacting the board. We hope that Elliot has been helpful to you.

We have discussed the matter with DJ.

JREF does not and will not have a blacklist. Currently the foundation has no plan to invite Radford to TAM or any other JREF function.

We are unsure if you are asking for anything more than this. –Chip

On Sat, Jul 20, 2013 at 4:26 PM, Karen Stollznow

wrote: Dear Board members,

I am a Research Fellow of the JREF and I wish to bring to your attention a situation that reflects poorly on our organization.

In February of this year I drew D.J.’s attention to a very serious matter. At TAM 2010 I was sexually assaulted and harassed by another speaker by the name of Benjamin Radford. I was also sexually harassed by him at TAM 2012. I had attempted to handle this both privately and professionally so as to not embarass the organizations involved. When Mr. Radford’s behavior continued I was then forced to file a formal complaint with his employer (CFI/CSI) to resolve the issue. An investigation was performed and he has since been found guilty. (I can supply evidence to attest to this decision.) D.J. put me in communication with Eliott Canter who has continued to be my JREF contact for this matter. My complaint is that D.J. is well aware of this situation and its severity, yet he continues to demonstrate public support for Mr. Radford on social media. Furthermore, he proudly and publicly advertised taking Mr. Radford out to the “Magic Castle” last night during his visit to L.A.

My request to the Board is that the JREF fulfill the obligation of its anti-sexual harassment policy by making a firm commitment to not invite this predator to any future JREF function. I also ask that D.J. cease his public displays of support for Mr. Radford which act as an endorsement for this man who is currently being disciplined by his employer for his actions.

In light of recent controversies within the skepticism movement it’s important that the gravity of this matter is acknowledged by the Board. The JREF needs to lead by example.

Thank you for your support. Dr. Karen Stollznow.

By the way, you can listen to Carrie Poppy’s podcast, or follow her on twitter.

She also sent along the JREF’s 990 form, in case you’re wondering where your money goes.

The latest furor over Ben Radford triggered some bad memories. Has anyone sat down and actually compiled a list of that guy’s offenses against reason and science? He’s got a long history of making a mess.

Remember when he was distorting the conclusions of papers about women’s eating disorders? Or how about the time he was taking issue with a four-year-old who notices the cultural biases in toys? That was fun; it led to Radford arguing that dolls are all pink because girls like pink because dolls are pink, and then inventing evo psych nonsense about color preferences and women searching for pink berries. Then he was dismissing concerns about the frequency of sexual harassment in schools, and picking nits over sexual assault so that he could argue that rape wasn’t so horribly frequent, a claim which revealed that he was innumerate.

Say…do you notice something? Is there a pattern to Radford’s biases? I mean, he’s well regarded otherwise, has a popular podcast, and I don’t think he’s stupid — the majority of the things he writes about are OK, it’s just that every once in a while he plumbs the depths of idiocy with a piece that makes him look like a hyperskeptical dishonest twit. And I think…if I look real hard…if I wipe the Y-chromosome bearing floaties out of my eyes…I see a common thread.

Whenever Radford writes about gender issues, like sexual assault, cultural assumptions about gender roles, or media biases about women, he turns into a lying hyperskeptical denialist. He stops being skeptical and starts digging for evidence, and worse, making up evidence, to bolster his presuppositions that discrimination against women doesn’t exist. He’s a bad skeptic. And he has a long history of doing this.

Why does he even have a job?

I don’t know if you want to read read Ron Lindsay’s explanation, but here it is anyway.

And what is it CFI was supposed to rebut? Ben’s speculations about the hues of dolls’ faces? Presumably not. What appeared to bother some commenters was Ben’s alleged sexism.

OK. CFI denounces sexism. We always have and presumably always will. Stereotyping based on gender is wrong and policies and practices that promote such stereotyping should be condemned. Furthermore, attitudes that exhibit sexism are unacceptable, and we should work to eliminate such attitudes, including, to the extent they exist, such attitudes within secular/skeptical organizations.

The problem is I doubt that Ben would disagree with anything in the above paragraph, nor did I see anything in his posts to suggest he would. Therefore, I’m not sure it counts as a “rebuttal.”

I love that blithe “OK”. Yeah, CFI denounces sexism, and Radford says he does, too, so what have you little people got to complain about?

But wait…I think I see another pattern emerging through my testosterone-addled murk. Look what Karen Stollznow said about her work environment — they have a history, too, of diminishing the significance of a pattern of behavior.

Five months after I lodged my complaint I received a letter that was riddled with legalese but acknowledged the guilt of this individual. They had found evidence of “inappropriate communications” and “inappropriate” conduct at conferences. However, they greatly reduced the severity of my claims. When I asked for clarification and a copy of the report they treated me like a nuisance. In response to my unanswered phone calls they sent a second letter that refused to allow me to view the report because they couldn’t release it to “the public”. They assured me they were disciplining the harasser but this turned out to be a mere slap on the wrist. He was suspended, while he was on vacation overseas. They offered no apology, that would be an admission of guilt, but they thanked me for bringing this serious matter to their attention. Then they asked me to not discuss this with anyone. This confidentiality served me at first; I wanted to retain my dignity and remain professional. Then I realized that they are trying to silence me, and this silence only keeps up appearances for them and protects the harasser.

Serial harassers are really, really good at looking wounded at accusations and apologizing verbally — they can be socially slick and glibly slide through these storms, because that’s what enables their activities. What you have to do is look at their patterns of behavior, what they do, not what they say. And Radford clearly has a sexist modus operandi.

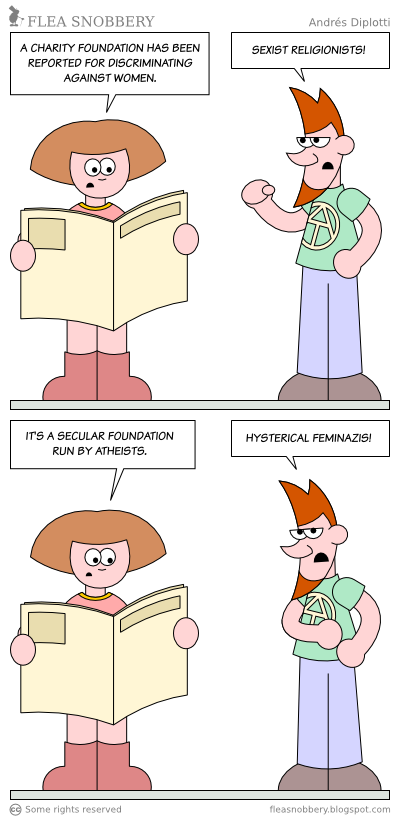

Nice cartoon:

via Flea Snobbery

Also, Rebecca Watson has a few words.

It’s shark week. I’m not going to watch a bit of it; I’m actually boycotting the Discovery Channel for the indefinite future. The reason: An appalling violation of media ethics and outright scientific dishonesty. They opened the week with a special “documentary” on Megalodon, the awesome 60 foot long shark that went extinct a few million years ago…or at least, that’s what the science says. The show outright lied to suggest that Megalodon might still exist somewhere in the ocean.

None of the institutions or agencies that appear in the film are affiliated with it in any way, nor have approved its contents.

Though certain events and characters in this film have been dramatized, sightings of “Submarine” continue to this day.

Megalodon was a real shark. Legends of giant sharks persist all over the world. There is still a debate about what they may be.

There is no evidence of this species’ persistence, nor did they present any. They just made it all up; reality isn’t awesome enough, so they had to gild the giant shark story. They’ve gone the way of our other so-called “documentary” channels dedicated to fact-based education — the History channel, Animal Planet, TLC. Garbage rules.

This also makes me sad because I already have to deal with irrational loons telling me that since coelacanths exist, scientists are wrong and humans walked with dinosaurs. I await with gritted teeth the first creationist who tries to argue that the survival of the Megalodon to modern times means it’s perfectly plausible that medieval knights hunted dragons/dinosaurs.

Thanks, Discovery Channel. And screw you.

I was surprised when I read the excerpt from the sneering letter to the editor-in-chief of Science magazine — it’s someone patronizingly chiding the little woman with the big job at a science journal in decline. It’s bad enough that it’s so condescendingly goofy, but it’s also complaining that Science has foolishly jumped into the “debate” about global climate change. There is no debate; it’s happening, there is a substantial anthropogenic component, and the science is rather firmly settled, so what would be then inappropriate is refusing to address an important environmental issue.

But then I read the full letter, and learned two things that made it even more laughable: 1) it’s an open letter published on the wacky denialist website, What’s Up With That, which means it’s going to be instantly ignored by any credible scientist, as Marcia McNutt is, and 2) it goes on and on and on and on. It’s absurdly preachy and unprofessional, and tells me that the author has no idea what kind of letter would be published by the magazine.

Further, McNutt is a professor of marine geophysics at Stanford, and what impresses the kook who wrote that letter?

McNutt is a NAUI-certified scuba diver and she trained in underwater demolition and explosives handling with the U.S. Navy UDT and SEAL Team.

The comments are also delusional. People are opining that Science is a dying journal. Really?

Climate change denialists are just about as out-of-touch and clownish as evolution denialists.

The sordid story of Colin McGinn, the sexist philosopher at the University of Miami who was compelled to leave his tenured post, is a rich source of academic pretension. The guy is a master at making up pseudo-intellectual excuses for repulsive creepiness.

Both Mr. McGinn and the student declined to provide any e-mails or other documents related to the case. But Amie Thomasson, a professor of philosophy at Miami, said the student, shortly after filing her complaint in September 2012, had shown her a stack of e-mails from Mr. McGinn. They included the message mentioning sex over the summer, along with a number of other sexually explicit messages, Ms. Thomasson said.

“This was not an academic discussion of human sexuality,” Ms. Thomasson said. “It was not just jokes. It was personal.”

Mr. McGinn said that “the ‘3 times’ e-mail,” as he referred to it, was not an actual proposal. “There was no propositioning,” he said in the interview. Properly understanding another e-mail to the student that included the crude term for masturbation, he added later via e-mail, depended on a distinction between “logical implication and conversational implicature.”

I gotta remember that “conversational implicature” line for when I’m caught plotting and conspiring. I suppose it beats just claiming academic authority as proof I can’t be a bad guy.